When Agents Learn to Navigate: Welcome to the AAIO Era

Imagine a world where your website is visited not just by humans bored during their coffee break, but also by artificial intelligence agents that navigate autonomously, make decisions, and complete transactions without a human finger ever touching a mouse. Welcome to 2026, where this scenario is no longer science fiction but a daily reality. And just as webmasters in the nineties had to adapt to Google's spiders, today we face a new revolution: Agentic AI Optimisation.

Guiding us into this new territory is Luciano Floridi, a Roman philosopher transplanted to Yale where he directs the Digital Ethics Center. Born in 1964, Floridi is not your classic academic locked in an ivory tower. After a classical education at Rome's La Sapienza, he moved through epistemology at Warwick and Oxford, before dedicating himself to what we now call the philosophy of information. The Italian government awarded him the title of Knight Grand Cross, the nation's highest honor, and for good reason: Floridi has worked as an ethics consultant for Google, collaborated with the European Commission on artificial intelligence, and helped shape the global debate on digital ethics.

In the paper published in April 2025 with a team from the Digital Ethics Center (Carlotta Buttaboni, Emmie Hine, Jessica Morley, Claudio Novelli, and Tyler Schroder), he formally introduces the concept of Agentic AI Optimisation. If Search Engine Optimization (SEO) has defined how we structure content for search algorithms, AAIO represents the necessary evolution for an era where AI doesn't just answer queries but acts autonomously.

What makes an AI "agentic"

Before delving into optimization, we need to understand what distinguishes an agentic artificial intelligence system from its predecessors. Floridi and his team identify three fundamental characteristics: autonomy in initiating actions without explicit instructions, decision-making ability based on context, and dynamic adaptability to digital environments.

We are not talking about glorified chatbots or voice assistants that execute predefined commands. An AAI system can, for example, navigate an e-commerce site, compare products according to complex criteria, check real-time availability, and complete a purchase by optimizing for multiple variables like price, delivery times, and seller sustainability. All without a human having specified every single step.

As Floridi writes in the paper, the success of these systems does not depend on their intelligence (which they technically do not possess) but on how well the digital environment is structured around their "agency without intelligence." This is where AAIO comes in.

From Optimisation for Humans to Optimisation for Agents

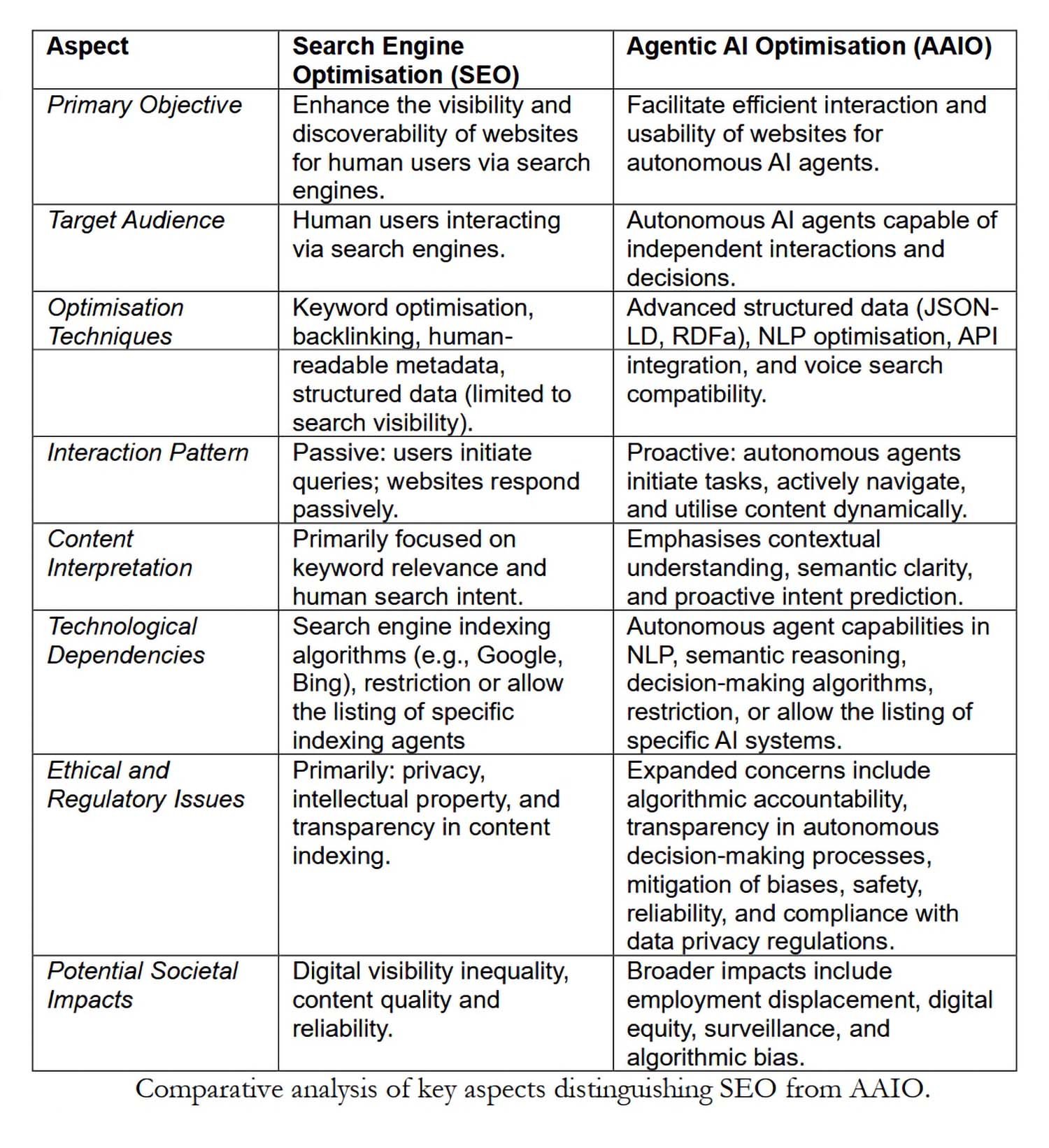

Traditional SEO was built around an architecture designed for humans navigating via browsers. Catchy titles, persuasive meta descriptions, perceived loading speed, responsive design: everything revolves around the human user experience. AAIO shares some of these fundamental principles (structured data, metadata, content accessibility) but extends and transforms them to meet the operational needs of autonomous agents.

A concrete example: while a clearly visible button that says "Buy Now" is sufficient for a human, an AI agent needs structured markup that unequivocally identifies that element as a transactional action, with all the collateral information (final price, taxes included, return policy) in machine-readable formats like JSON-LD or RDFa based on Schema.org.

Floridi's paper identifies four technical pillars of AAIO. The first is the implementation of advanced structured data that goes beyond basic SEO markup, providing complete context for every entity and relationship on the site. The second concerns the optimization of the information architecture: clear hierarchies, logical navigation, well-documented API endpoints. The third is semantic accessibility, which means providing text alternatives, detailed descriptions, and contextual metadata for every multimedia element. The fourth is the optimization of the content itself through regular updates, precise targeting of intent (no longer just human but also agentic), and AI-based analytics for continuous improvement.

The Etiquette of Robots: Managing Agent Access

An immediate practical question is: how do we control which AI agents can access our content? The answer lies in evolutions of the classic robots.txt file. While this tool was created to tell search engine spiders where they can go, today we have to deal with specific user-agents like OpenAI's GPTBot, Anthropic's ClaudeBot, or Google-Extended for Google's models.

Each agent presents itself with a unique identifying string in HTTP requests. A webmaster can decide to allow access to all, selectively block some agents, or implement strict whitelists. Floridi notes in the paper that some sites are adopting LLMs.txt files, a proposal that gathers all the site's content into a single text document optimized for analysis by Large Language Models.

The issue is not only technical but also economic and strategic. If an AI agent can navigate, extract information, and complete transactions autonomously, who benefits from the engagement? Who pays for the hosting? Who collects the valuable behavioral data for marketing? These are questions reminiscent of the early debates on web scraping and copyright, but with deeper implications.

The Industry is Moving: AgentKit, MCP, and the Race for Standards

While Floridi and his team propose rules, the tech giants build. OpenAI has transformed its experimental Swarm framework into AgentKit, a complete suite for building, deploying, and optimizing autonomous agents. Launched in October 2025, AgentKit includes a visual Agent Builder for composing multi-agent workflows, a centralized Connector Registry for managing data integrations, and ChatKit for embedding conversational interfaces. Companies like Klarna have built support agents that handle two-thirds of tickets using these tools, while Clay has increased its growth tenfold with automated sales agents.

But the real revolution could come from an open standard. Anthropic has released the Model Context Protocol, a universal protocol for connecting AI systems to external data sources. Think of MCP as a USB-C for AI applications: a standardized interface that eliminates the need for custom integrations for every combination of model and external system. Since its launch in November 2024, the community has built thousands of MCP servers, with SDKs available for all major languages and over 97 million monthly downloads between Python and TypeScript.

The strategic importance of MCP is such that in January 2025, Anthropic donated it to the Agentic AI Foundation, a directed fund under the Linux Foundation co-founded by Anthropic, Block, and OpenAI, with support from Google, Microsoft, AWS, Cloudflare, and Bloomberg. This move transforms MCP from a proprietary protocol into a neutral industry standard, potentially accelerating the adoption of AAIO on a global scale.

The Virtuous (or Vicious) Circle

The paper introduces a fascinating concept: the symbiotic relationship between platform optimization and AI performance. The more sites that implement AAIO, the better the performance of AI agents becomes. More effective agents incentivize more platforms to optimize. This virtuous circle is reminiscent of the evolution of SEO, where well-optimized sites improved Google, which in turn rewarded optimization with higher rankings.

But there is a crucial difference. With SEO, the benefit was mutual but asymmetrical: Google gained data and traffic, while sites gained visibility. With AAIO, the dynamic is more complex. If an AI agent completes a transaction on an optimized e-commerce site, who captures the value of the customer relationship? The agent knows the user has specific preferences, has tracked purchasing behavior, has collected feedback. This behavioral data, traditionally pure gold for marketers, now flows to whoever controls the agent.

Floridi and his team raise crucial questions: who is left out of this circle? The implementation of AAIO requires technical skills, resources, and access to documentation that not everyone possesses. Small businesses, non-profit organizations, and independent content creators could find themselves marginalized in a digital ecosystem increasingly optimized for tech giants that can afford dedicated AAIO teams.

This digital divide is not accidental but structural. As the authors write, there is a real risk that AAIO will amplify existing inequalities in access to the benefits of the digital economy. It is the same dynamic we saw with programmatic advertising, where those with the resources to optimize in real-time dominated, leaving behind those who could not afford sophisticated infrastructure.

The GELSI Implications: Governance, Ethics, Law, and Society

The densest and most interesting section of the paper addresses the GELSI (Governance, Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications), a term that Floridi has helped popularize in technology ethics studies.

On the governance front, the fundamental question is: who should develop AAIO standards? An organic process led by the industry, as happened with many web standards? Or a multi-stakeholder approach that includes regulators, academics, civil society, and end-users? The history of SEO suggests that standards that emerge from the bottom up tend to favor those who already hold technological and economic power.

The ethical questions are even thornier. When an autonomous AI agent makes a mistake based on AAIO-optimized content, who is responsible? The site owner who provided incorrect structured data? The agent's developer who did not adequately validate the information? The end-user who delegated the decision to the AI?

Floridi emphasizes that current ethical frameworks are not prepared for scenarios where agency is distributed among humans, algorithms, and digital infrastructures. The concept of "agency without intelligence" that he developed in previous works becomes particularly relevant: these systems act without understanding, decide without judging, and influence without intentionality.

On the legal side, the paper highlights immediate tensions with the European GDPR. If an AI agent collects and processes personal data while browsing AAIO-optimized sites, who is the data controller? Current legal categories of "data collection" presuppose direct human intentionality. But in scenarios where an agent operates autonomously following high-level objectives, the chain of responsibility shatters.

Then there is the issue of the European AI Act, which came into force in 2024. This regulatory framework was designed before agentic AI became mainstream, and it struggles to classify these systems. Are they tools? Are they autonomous? Do they require continuous human supervision or can they operate independently? Floridi notes that regulatory ambiguity could slow down the beneficial adoption of agentic AI, but also open up spaces for abuse in less stringent jurisdictions.

The Concrete Risks: Manipulation, Bias, and Surveillance

The paper does not limit itself to philosophical speculation but identifies tangible and current risks. The first is manipulation: AAIO-optimized sites could be designed to subtly influence the decisions of AI agents, much like dark patterns do with humans, but with greater effectiveness since agents have no innate skepticism.

The second concerns the amplification of bias. If the datasets on which AI agents are trained already reflect systemic prejudices, and if AAIO-optimized sites reinforce certain informational patterns at the expense of others, the result is a feedback loop that solidifies existing discrimination. Floridi explicitly cites the work of Virginia Eubanks on how automated systems amplify inequalities.

The third risk is surveillance. Every interaction between an AI agent and an AAIO-optimized site generates granular data on behaviors, preferences, and decision-making patterns. Who controls this data? How is it monetized? What protections exist against abuse?

What Needs to Be Done Now

In the concluding section, Floridi and his team propose concrete directions. On the technical side, there is an urgent need for the development of open and interoperable standards for AAIO, managed by multi-stakeholder consortia rather than single corporations. On the regulatory side, legislators must update frameworks like the GDPR and the AI Act to explicitly address distributed agency and autonomous interactions.

On the educational front, there is a need to train a new generation of professionals who understand both the technical aspects of AAIO and its ethical and social implications. It is not enough to know how to implement JSON-LD; one must understand how those technical choices influence who will have access to the benefits of the agentic economy and who will be left out.

The paper closes with a call for proactivity. As Floridi has pointed out on other occasions: "The best way to catch the technology train is not to chase it, but to be at the next station." We must address the GELSI implications of AAIO now, before the patterns become cemented in infrastructures that are difficult to change.

The era of agentic AI is not a hypothetical future but a rapidly evolving present. AAIO is not a technology we can afford to ignore or relegate to IT departments alone. It is a matter that concerns the very architecture of our digital ecosystem, with ramifications that touch upon the economy, democracy, social equity, and individual rights.

The question is not whether we should optimize for AI agents, but how to do so in a way that serves the collective interest and not just that of those who already hold technological power. It is a challenge that requires, as always in Floridi's work, thinking philosophically about technology before technology thinks for us.