Consumer AI in 2025: Why More Choice Didn't Create More Change

2025 was supposed to be the year of maturity for consumer artificial intelligence. OpenAI introduced dozens of features: GPT-4o Image, which added a million users per hour at its peak, the standalone Sora app, group chats, Tasks, Study Mode. Google responded with Nano Banana, which generated 200 million images in its first week, followed by Veo 3 for video. Anthropic launched Skills and Artifacts. xAI took Grok from zero to 9.5 million daily active users. A frenetic pace of activity, a continuously expanding catalog.

Yet, users didn't switch. Less than 10% of ChatGPT's weekly users visited even one other major model provider throughout the year. Data from Yipit shows that only 9% of consumers pay for more than one subscription among ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, and Cursor. The labs' race for innovation collided with a wall of behavioral inertia. As in the paradox of choice described by Barry Schwartz, more options did not lead to more switching, but to decision paralysis.

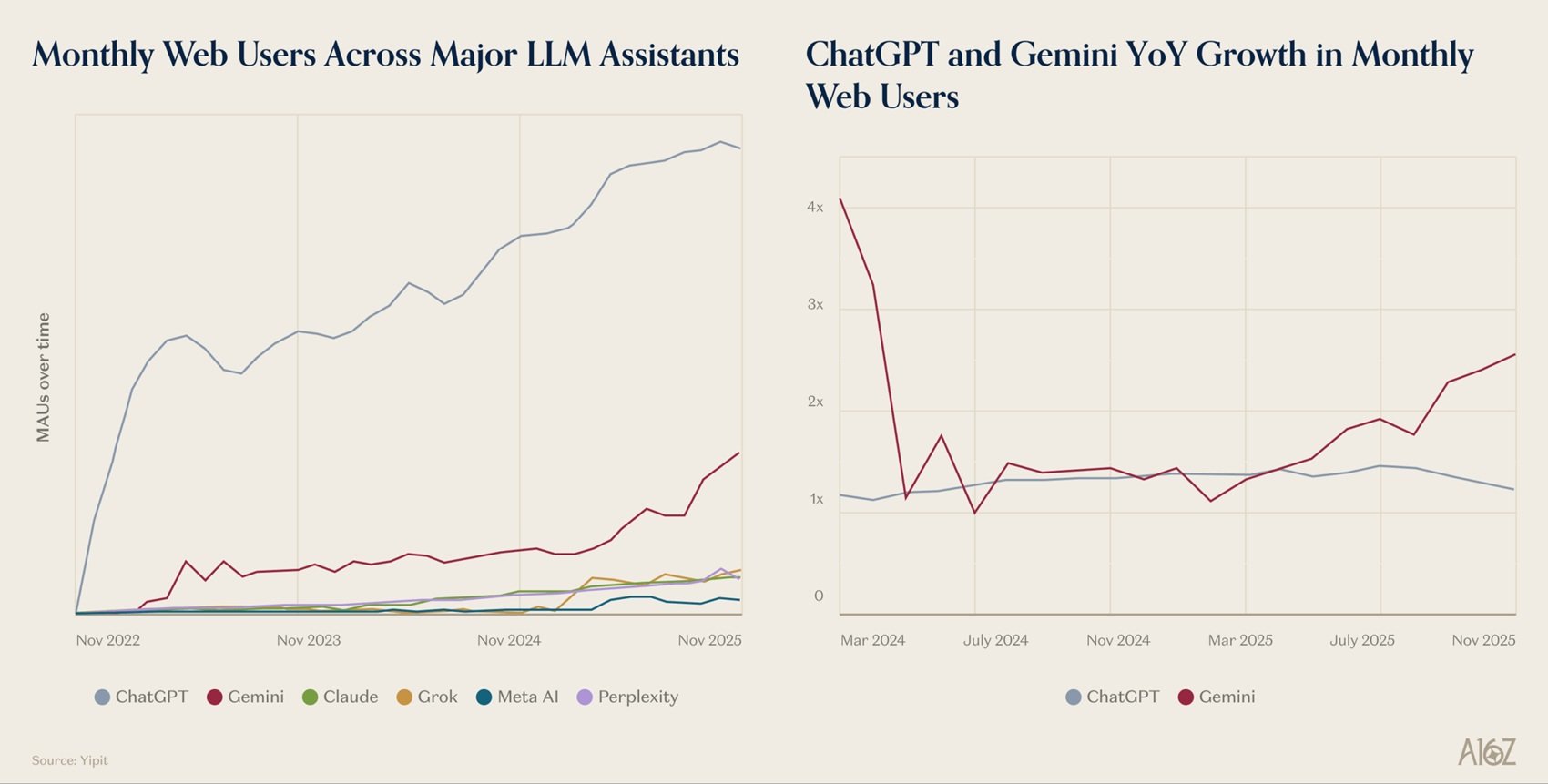

The analysis by Andreessen Horowitz captures a profound dissonance: overall AI usage grew, but the diversification of choices did not. The market expanded vertically, not horizontally. Users used more of what they already used, rarely exploring alternatives. It's as if 2025 proved that in consumer AI, the winner isn't the one who innovates the most, but the one who first captures the habit.

The Monarchy of ChatGPT

The numbers tell a story of overwhelming dominance. ChatGPT reached between 800 and 900 million weekly active users across all platforms, consolidating its position after becoming the fastest product ever to hit 100 million users in 2023. Gemini, the runner-up, stands at 34% of ChatGPT's scale on the web and 40% on mobile. But it's on the engagement front that the gap becomes a chasm: ChatGPT boasts a DAU/MAU of 36%, nearly double Gemini's 21%. And the 12-month retention on desktop tells the same story: 50% versus 25%.

These are not just market data; they are indicators of ingrained habits. Double the retention means that for every user Gemini manages to keep after a year, ChatGPT keeps two. The higher DAU/MAU indicates that users return more frequently, turning ChatGPT into a daily habit rather than an occasional tool. Like an athlete's muscle memory, where every movement becomes automatic after hours of practice, ChatGPT's interface has settled into the procedural memory of hundreds of millions of people.

OpenAI's strategy for 2025 was clear: consolidate everything within ChatGPT. Pulse for daily updates, Group Chats for collaboration, Record for transcriptions, Shopping Research, Tasks, Study Mode. Every new feature was pushed through the existing interface. But as the a16z analysis notes, none of these experiences truly broke through in terms of usage or retention. The problem? It's hard to offer a first-class experience when you have to operate within the constraints of an already crowded, general-purpose interface.

The exceptions prove the rule. Sora, launched as a standalone app, surpassed 12 million global downloads as a creative tool but failed as a social app with less than 8% retention on day 30, well below the 30% threshold for successful consumer apps. Atlas, ChatGPT's browser, is a powerful product, but less than 5% of users visited the download page, limited to macOS and overshadowed by the dominance of the chat interface.

The Feature Graveyard

There is a recurring pattern in the 2025 strategies of the major labs: feature overload. OpenAI integrated Connectors to link ChatGPT with G Suite, Microsoft, Notion, Stripe, Slack. It launched Agent to generate presentations and analyses, though in testing, it still proves slow and unstable. Google released Portraits, Doppl, Whisk, Gems—a sequence of experiments that saw limited traction. Anthropic added Voice Mode, Memory, Web Search, Research, catching up on features that ChatGPT had for some time.

But the problem isn't technical quality. It's that every new feature is added to an already saturated interface. Like in Metal Gear Solid V, where Kojima had accumulated so many gameplay systems that the learning curve discouraged new players, consumer AI risks suffocating under the weight of its own capabilities. Steve Krug, in his classic "Don't Make Me Think," argued that every choice required of the user is a cognitive cost. When you open ChatGPT today, you are faced with: standard chat, voice chat, Canvas for documents, Agent for complex tasks, Tasks for reminders, Study Mode for learning, Shopping Research, Sora for video. Eight different modes, each with its own specific logic.

The result is that most users stick to what they know. The adoption curve for new features is slow, and passive discovery is almost nonexistent. Google took the opposite approach: creating dedicated surfaces. NotebookLM, launched as a separate product, saw its web users more than double year-over-year in November, and the mobile app, released in May, has 8 million monthly active users. The product continues to evolve with slide generation, video overviews, and infographics, but without polluting the core Gemini experience.

This dichotomy reflects a fundamental tension in product design: concentration versus diversification. OpenAI is betting that the winning distribution strategy is to have everything in one place. Google is experimenting with the idea that dedicated experiences can have a life of their own. The data suggests that when a product has a clear and distinctive job-to-be-done, users adopt it. When it's one feature among many, even if technically superior, it struggles to stand out.

The Distribution Trap

Google should be winning by a landslide. Gemini is integrated into Chrome, Gmail, Meet, Android. It's pre-installed on billions of devices. Yet ChatGPT, which users have to actively seek out, maintains a three-to-one scale advantage on the web. How is this possible? The answer lies in a misunderstanding of what distribution means in the AI era.

Passive distribution works when the user has no credible alternatives or when the cost of switching is prohibitive. But AI is different. Users have already chosen their preferred assistant, built a mental model of how to interact with it, and accumulated conversations and context. Switching to Gemini doesn't just mean opening a new app; it means retraining cognitive habits. It's like asking a guitarist who has played a Gibson for twenty years to switch to a Fender: technically, they can do the same things, but the feel is different, and that feel matters.

Yet Gemini is accelerating. Its desktop user growth is 155% year-over-year compared to ChatGPT's 23%, and the pace has increased for the last five consecutive months. Nano Banana, the viral image generation model, brought in 10 million new users in its first week. On the paid front, Gemini is growing even faster: almost 300% year-over-year for Pro subscriptions, versus ChatGPT's 155%. The retention of paying users is getting closer: 68% at the 12-month mark for ChatGPT, 57% for Gemini.

These numbers show that the game is not over. Google is finding angles of attack: viral models that generate organic word-of-mouth, integration into existing workflows that lowers cognitive barriers, and aggressive pricing to convert free users. But it's an uphill battle. ChatGPT has the first-mover advantage, amplified by the network effect of shared conversations and a brand awareness that borders on generic (like Google for search, ChatGPT is becoming synonymous with AI chat).

Google's attempt to insert an AI Mode into search, available since May, shows only 2% of weekly users interacting with it. Distribution matters, but it's not enough. There needs to be a compelling reason to change habits, and that reason can't just be "we have AI too."

The Exception That Proves the Rule

While the giants clash on the same ground of general-purpose chats, some startups are showing that there are alternative ways to win. The model is simple: identify a vertical use case, build a dedicated experience optimized for that specific job, and avoid the noise of generalist features.

Character AI for companionship and role-playing, Suno for music generation, Eleven Labs for synthetic voices, Replit for collaborative coding, Gamma for presentations, Lovable and Manus for design. Each of these products has reached millions of users and, as a16z notes, has grown revenue faster than ever before in the history of consumer software. The secret? Defined interfaces that provide specific superpowers instead of promising infinite capabilities.

Anthropic understood this lesson. Instead of chasing the mass market, it focused on the technical prosumer. Claude Code, the command-line tool for agentic coding, reached a one-billion-dollar run rate in six months. Skills and Artifacts, launched during the year, are powerful services for sophisticated users who don't need to be hand-held. The strategy is clear: it's better to be indispensable to a million developers than marginally useful to a hundred million casual users.

Perplexity follows a similar philosophy. Comet, their AI browser, surpassed one million users by targeting the "productivity hacker" who wants to integrate search into their workflow. The Email Assistant and conversational shopping tools build an ecosystem for those who want to maximize efficiency. With over 20 million monthly active users and a $100 million run rate announced in March, Perplexity proves there is room for focused players.

xAI has also found its niche. Grok, which had zero standalone users at the beginning of the year, ends December with 9.5 million daily active users and 38 million monthly. Its bet on Companions with controversial personalities and on video generation models with audio and fast lip-sync has created a distinctive positioning. Deep integration with X, where you can edit any image in the timeline with a long tap, transforms AI into a native layer of the social network.

These cases suggest that the future of consumer AI will not be winner-take-all, but winner-by-category. The large general-purpose models will capture the majority of the mainstream market but will leave ample room for excellent vertical experiences. As in gaming, where Call of Duty dominates shooters but Hades conquers roguelike lovers, AI will have generalist blockbusters and specialized cult hits.

The Difficult Choices of 2026

2026 opens with three fundamental questions that will define the next phase of consumer AI. The first concerns monetization. With only 5% of ChatGPT users paying, and an estimated 1.8 billion people using consumer AI, the gap between usage and revenue is enormous. Subscriptions alone are not enough. OpenAI is experimenting with advertising, Perplexity with transaction and affiliate fees for shopping, and others with agent marketplaces. A sustainable economic model has yet to emerge.

The second question is about user experience saturation. Will the labs continue to pile capabilities onto existing interfaces? If so, we risk cognitive collapse: too many functions, too many modes, too much complexity for the average user. The alternative is to proliferate dedicated apps, but this requires huge investments in marketing and user acquisition for each one. Apple demonstrated with its native iOS apps that it can be done, but it requires an ecosystem vision that the AI labs have yet to articulate clearly.

The third question concerns discovery. How do users find new features? OpenAI is launching Apps, an infrastructure to allow third-party developers to build experiences within ChatGPT. If it works, it could become the first truly new consumer platform in over a decade. But it must solve the Connectors paradox: giving developers enough freedom to create magic without fragmenting the core experience. A feat that has caused many to fail before, from Facebook Platform to Amazon Alexa Skills.

Meanwhile, user behavior remains the most resistant factor to change. Inertia is not laziness; it's cognitive economics. Changing tools means relearning interaction patterns, rebuilding trust in the quality of the output, and migrating context and history. The cost is real, even if invisible. To overcome it, a perceived advantage must be enormous, not incremental. Gemini is gaining ground by offering viral creative models. Claude is winning over developers with superior performance on technical tasks. Meta and xAI are betting on native integration into their social networks. But no one has yet found the magic formula for mass switching.

The real risk is that the gap between technical capabilities and real-world adoption will continue to widen. The labs improve their models every quarter, add multimodal capabilities, expand the context window, and reduce latency. But if 90% of users still only use one assistant, and 91% pay for at most one, all this computational power turns into product overfitting. It's like having a car that can go 400 km/h when the speed limit is 130: impressive on paper, irrelevant in daily use.

2025 has shown that in consumer AI, technology is not enough. It requires design that reduces complexity instead of accumulating it, distribution that creates habits instead of mere presence, and value propositions so clear that the user doesn't have to think. The labs that understand this will win 2026. The others will continue to build cathedrals in the desert—perfect and empty.