AI Makes You More Skilled, Not Wiser. Overestimating Your Own Knowledge

Imagine taking the American law school admission test with ChatGPT by your side. Your results improve significantly: three points higher than those who take the exam alone. Yet, when you are asked to evaluate your own performance, you overestimate it by four points. Not only that: the more you technically know about how artificial intelligence works, the more this illusion of competence is amplified. Welcome to the paradox of augmented cognition, where becoming better simultaneously means losing the ability to understand how good we really are.

The Paradox of Augmented Performance

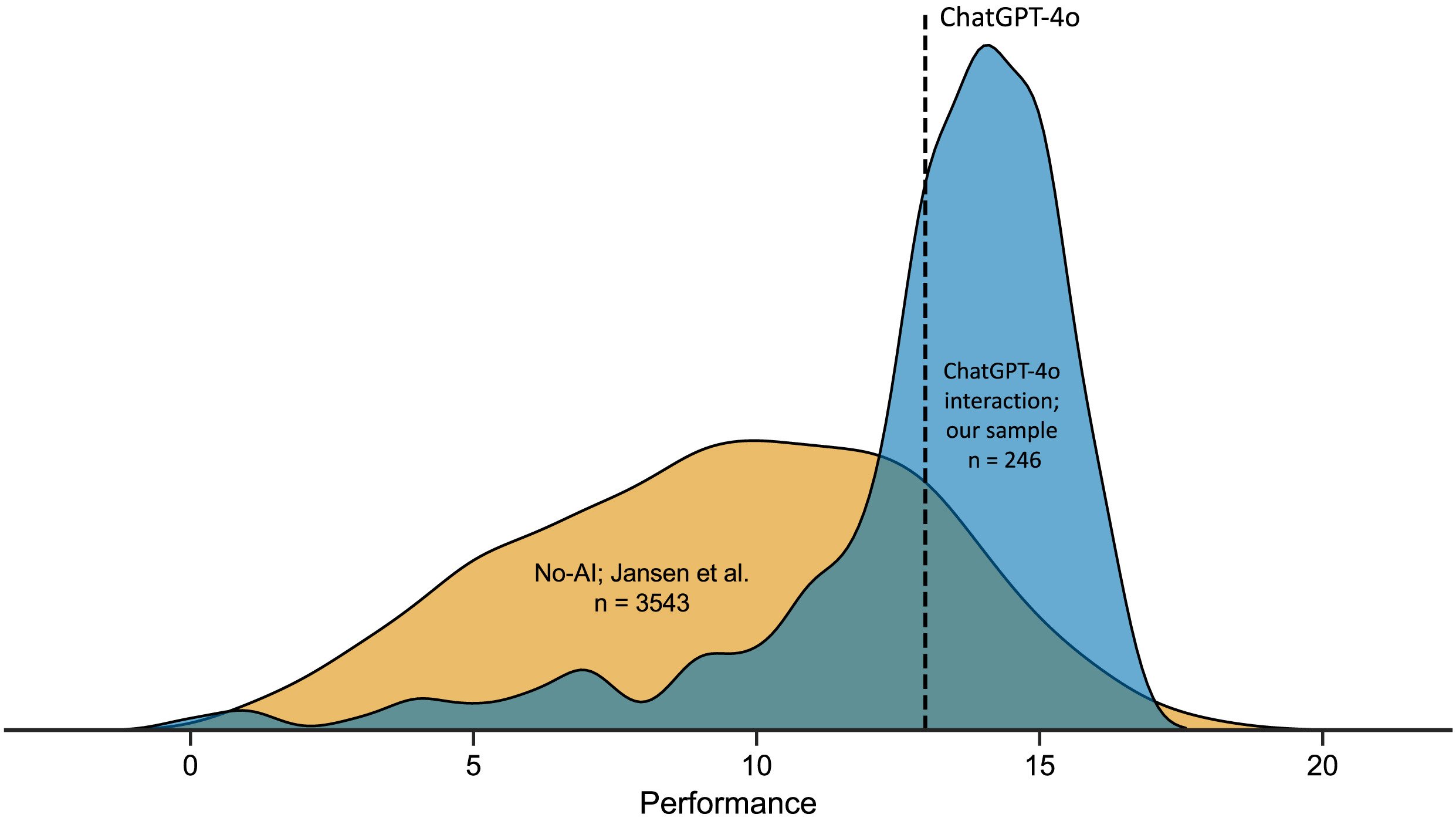

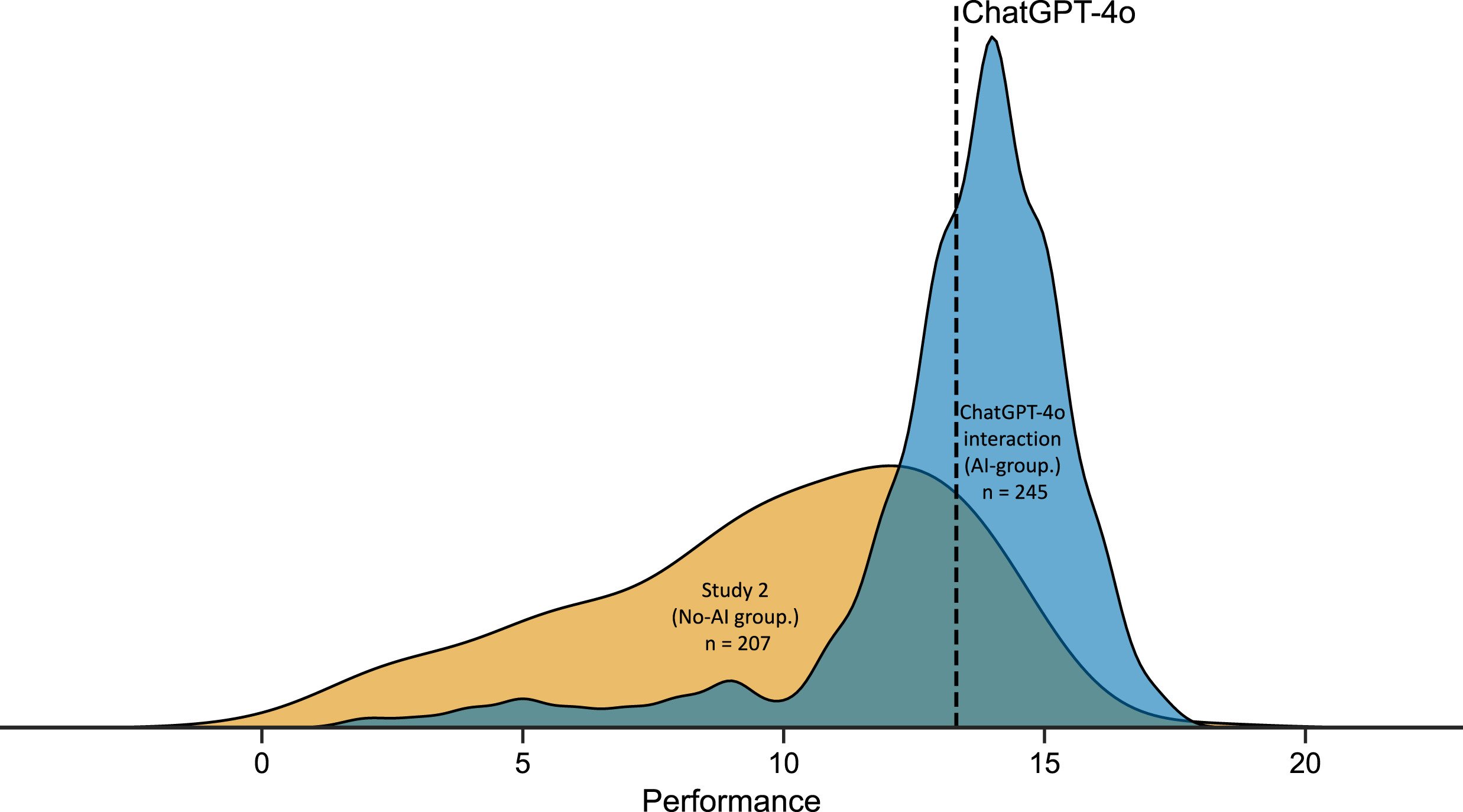

The research conducted by Aalto University and published in Computers in Human Behavior subjected 246 participants to twenty logical reasoning questions from the LSAT, the standardized test for admission to American law schools. Half of the sample could freely consult ChatGPT-4o during the solving process, while the other half proceeded on their own. The numbers tell an ambivalent story: those who used AI obtained average scores of 12.98 out of 20, compared to 9.45 for those who worked without assistance. A 37% improvement that, on paper, would confirm the promises of augmented intelligence.

But there is an uncomfortable detail. When the participants in the AI group were asked to estimate how many answers they had provided correctly, the average of their predictions was 16.50 out of 20. A systematic overestimation of about four points, double that of the control group. It's as if access to a powerful tool had not only enhanced their actual abilities but had simultaneously distorted their perception of those abilities to an even greater extent.

The phenomenon is reminiscent of that feeling we have all experienced while scrolling through Wikipedia at three in the morning: after reading three articles on the exoskeleton of crustaceans, we suddenly feel like experts in marine biology. Psychologists call this mechanism the "illusion of explanatory depth," and it works like this: when information is easily accessible, our brain confuses it with information that is possessed. In the case of AI, however, the effect is amplified by the conversational nature of the interaction: ChatGPT does not just return a piece of data, it builds an articulated narrative that mimics the cognitive process itself.

Daniela Fernandes, the first author of the study, observed that the majority of participants interacted with ChatGPT in a surprisingly superficial way. 46% sent only one prompt per problem, copying the question into the interface and accepting the answer without further investigation. It's like relying on the first Google search result without checking the sources, but with more subtle consequences: you are not just delegating the search for information, you are outsourcing the reasoning process itself.

The Disappearance of the Dunning-Kruger Effect

For decades, one of the most studied phenomena in cognitive psychology has been the Dunning-Kruger effect: that systematic tendency of less competent individuals to drastically overestimate their own abilities, while the most prepared tend to a modest underestimation. It is the principle that explains why the colleague who barely knows how to open an Excel sheet confidently offers to manage the company database, while the computer engineer hesitates before giving an opinion.

In logical reasoning tests conducted without AI, this pattern emerges with mathematical regularity: those who are in the lowest performance profile tend to believe they belong to the middle-to-high range, while those who excel often place themselves lower than they deserve. It is a calibration effect inversely proportional to actual competence, fueled by what researchers call "metacognitive noise": the background noise that interferes with our ability to self-assess.

But when the Aalto researchers applied a Bayesian computational model to the data from the group that used ChatGPT, they discovered something unexpected. The Dunning-Kruger effect simply disappeared. It was not reduced or attenuated: it ceased to exist as a statistically relevant pattern. All participants, regardless of their actual performance, showed similar levels of overestimation. It's as if the AI had leveled not only the skills, but also the inability to accurately assess them.

The underlying mechanism is counterintuitive but logical. The Dunning-Kruger effect emerges from the correlation between task ability and metacognitive ability, that is, the ability to monitor the quality of one's own reasoning. Those who are good at solving logical problems are also good at recognizing when their solution holds up or falls apart. But when ChatGPT comes into play, this correlation breaks: the AI provides outputs of relatively uniform quality to everyone, regardless of the individual user's ability to assess their validity. The result is a performance leveled upwards and a metacognition leveled downwards. Everyone improves, but no one really knows by how much.

Robin Welsch, a cognitive psychologist and supervisor of the research, observed that this represents a reversal of the cognitive augmentation hypothesis formulated in the 1960s by Doug Engelbart. The original idea was that technologies could amplify human intellect while maintaining or improving critical awareness. Instead, we are witnessing an asymmetric amplification: capabilities grow, wisdom stagnates.

Technological Literacy as a Boomerang

If there is one result of the study that overturns common assumptions about the relationship between competence and conscious use of technology, it is the correlation between AI literacy and metacognitive accuracy. The researchers measured the AI literacy of the participants using the SNAIL (Scale for the assessment of non-experts' AI literacy) scale, which assesses three dimensions: technical understanding of how the systems work, ability to critically evaluate the outputs, and skill in practical application.

What one would expect is a positive relationship: those who know AI better should use it more consciously, recognize its limits, and better calibrate their trust in its suggestions. Instead, the data show the opposite. Participants with higher scores in the "technical understanding" dimension were systematically less accurate in their self-assessments. The more they knew about prompt engineering, model temperature, and transformer architectures, the more they overestimated the quality of their work with AI.

It is an effect reminiscent of that scene from Primer, Shane Carruth's cult film about time travel, where the protagonists become so immersed in the technical complexity of their machine that they completely lose sight of the implications of what they are building. Familiarity with the mechanism does not guarantee wisdom in its use. On the contrary, it can create a false sense of control: "I know how this thing works, so I can trust the results it gives me."

Thomas Kosch, an expert in human-computer interaction and co-author of the study, suggests that this paradox stems from a fundamental misunderstanding of what it means to "know" an AI system. Technically understanding a large language model means knowing that it processes text through attention layers, that it predicts the next token by maximizing probability, that it can be fine-tuned on specific datasets. But this procedural knowledge does not automatically translate into epistemic awareness: knowing when the model is producing a reliable answer and when it is simply generating plausible text.

The research group found a positive correlation between all three factors of the SNAIL scale and the average confidence of the participants. Those who knew more felt more confident. But this confidence did not translate into a better ability to discriminate between correct and incorrect answers: the area under the ROC curve, which measures how well confidence judgments predict actual accuracy, remained stable or even decreased as AI literacy increased. The more you know, the more you trust, but you don't necessarily judge better.

The Collapse of Metacognition

To understand how deep the metacognitive deficit induced by the use of AI is, the researchers analyzed not only the overall performance estimates (how many questions do you think you answered correctly?), but also the step-by-step confidence judgments: after each single problem, participants rated on a scale from 0 to 100 how confident they were in their answer.

Under normal conditions, these judgments should be predictive: high confidence for correct answers, low for wrong ones. It is the signal that the metacognitive system is working, that there is a feedback loop between the decision-making process and the monitoring of the quality of that process. But in the group that used ChatGPT, this correlation was significantly attenuated. The average confidence for correct answers was only marginally higher than that for wrong answers, with an average AUC of 0.62, just above the level of randomness and well below the threshold of 0.70 that psychologists consider an indicator of "moderate metacognitive sensitivity."

In practice, the participants felt more or less confident all the time, regardless of whether they were providing the right or wrong answer. It's like driving with the dashboard covered: the vehicle works, but you have no idea if you are going at thirty or one hundred and thirty miles per hour.

This collapse of metacognitive sensitivity has implications that go far beyond logic tests. Think of a doctor using a diagnostic AI system: if their ability to distinguish between reliable diagnoses and dubious ones is compromised by the ease with which the AI produces formally convincing outputs, the result is not an improvement in clinical practice but a potential increase in risk. Or a student preparing for an exam using ChatGPT to solve problems: if immediate access to solutions convinces them that they have understood the subject, they will go to the exam with an illusory sense of preparation.

The phenomenon is aggravated by what Stephen Fleming, a cognitive neuroscientist at University College London, calls the "fluency heuristic": when information is processed quickly and effortlessly, the brain interprets it as a sign of competence. ChatGPT returns elaborate, articulated, impeccably formatted, and almost instantaneous answers. Every aspect of this experience shouts "this is correct" to our intuitive system, bypassing the deliberative analysis that we normally activate when faced with uncertain information.

Rethinking Intelligent Interfaces

The question then becomes: if AI actually improves performance but deteriorates critical awareness, how do we design systems that maintain the benefits while minimizing the harm? The answer cannot be limited to "let's use it less" or "let's trust it less." The genie is out of the bottle, and tens of millions of people daily use tools like ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini to reason, write, and solve problems.

The researchers propose what they call an "explain-back micro-task": before accepting an AI-generated answer, the user must rephrase it in their own words, making the underlying logic explicit. It is a technique that forces a shift from superficial learning, based on pattern recognition, to deep learning, based on structural understanding. If you ask ChatGPT to solve a physics problem and then you have to explain in your own words why that solution works, the system forces you into a direct confrontation with your actual understanding.

Another promising direction concerns the explicit calibration of confidence. Instead of letting the user implicitly infer the reliability of an answer from the model's assertive tone, the interface could display uncertainty metrics: how "sure" the model is of the answer in terms of probability distribution, whether there are plausible alternative answers, how much the question deviates from the training set. It is not a perfect solution because users still tend to ignore these signals when the output appears convincing, but at least it introduces an element of cognitive friction.

Human-AI interaction experts are also exploring more radical architectures, such as metacognitive agents: secondary AI systems whose task is not to help you solve the problem, but to monitor how you are solving the problem with the help of the first AI. A sort of cognitive supervisor that intervenes when it detects patterns of overreliance or uncritical acceptance. It sounds like science fiction, but some preliminary experiments show significant reductions in performance overestimation when this type of metacognitive scaffolding is implemented.

Falk Lieder, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute, has proposed an even more ambitious framework: interfaces that dynamically adapt to the user's level of metacognitive competence. When the system detects that you are trusting the outputs too blindly, it increases the level of ambiguity of the answers, inserts more marked uncertainty signals, and asks you to justify your choices. When you instead demonstrate critical ability, it retracts and leaves more autonomy. It is a model that overturns the current logic, where the AI tries to be increasingly fluid and assistive, to instead introduce a strategy of "calibrated assistance."

The risk, of course, is that these interventions create such friction as to make the tools less appealing. If every time I ask ChatGPT to help me with a problem I have to go through a metacognitive quiz before seeing the answer, I am likely to stop using it. But perhaps that is precisely the point: the goal should not be to maximize engagement with AI, but to optimize cognitive augmentation in the fullest sense, including the metacognitive dimension.

Janet Rafner, who studies the sociotechnical implications of AI at the Copenhagen Institute, suggests that the problem requires solutions on multiple levels. In the short term, better interface designs. In the medium term, educational programs that teach not only technical AI literacy but also metacognitive literacy. In the long term, a cultural reconsideration of what competence means in a world where access to external cognitive abilities is ubiquitous. It is a challenge reminiscent of that faced by writing itself millennia ago: when you have at your disposal the external memory of the written word, what happens to internal memory? And above all, what happens to your awareness of what you really remember and what you have only transcribed?

The research from Aalto University does not offer definitive solutions, but it precisely identifies a problem that risked remaining submerged under the enthusiasm for performance gains. AI makes us smarter in the computational sense: we solve more problems, faster, with fewer errors. But it does not make us wiser in the metacognitive sense: we do not improve in our ability to critically evaluate our own cognitive processes, to recognize when we are truly understanding and when we are just simulating understanding.

It is the difference between Deckard and the replicants in Blade Runner: they all possess memories, but only some know which are authentically their own. In our case, we all get better answers with AI, but we risk losing the ability to distinguish between genuine understanding and borrowed competence. And in a world where more and more important decisions are made with the assistance of intelligent systems, that distinction could make all the difference.