The Future of AI: Will the Bubble Burst and Winter Return?

Like the protagonist of Memento who discovers he can't trust his own memory, the artificial intelligence of 2025 is facing an uncomfortable truth: maybe it's not as smart as we thought. Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, recently admitted what many had been whispering in the corridors of Silicon Valley: the AI market is in a bubble, just as it was with the dot-coms at the dawn of the new millennium. History, as often happens in the tech world, seems destined to repeat itself with a script written decades ago.

The eternal return of the digital winter?

To understand where we are going, we need to look at where we come from. The term "AI winter," coined in 1984 during a public debate at the AAAI, describes those recurring periods when enthusiasm for artificial intelligence gives way to disappointment, followed by drastic cuts in funding and, finally, the abandonment of serious research. Roger Schank and Marvin Minsky, two pioneers who had experienced the first winter of the 1970s firsthand, compared this phenomenon to a "nuclear winter": a chain reaction that begins with pessimism in the scientific community, spreads through the media, and culminates in the end of funding.

The nuclear metaphor was not accidental. As in the science fiction films of the 1980s, where post-apocalyptic scenarios represented the fears of the era, the AI winter reflected the anxiety of a sector that had promised too much and delivered too little. The first major collapse came between 1974 and 1980, followed by a second glacial period between 1987 and 2000.

The tale of two winters

The first AI winter has deep roots in the failure of machine translation. In the 1950s and 1960s, the Cold War had fueled dreams of machines capable of instantly translating Russian documents. The Georgetown-IBM experiment of 1954 had translated just 49 Russian sentences into English, using a vocabulary of only 250 words, but the newspaper headlines spoke of "polyglot robot brains." As often happens, the media had amplified a limited demonstration, turning it into an imminent revolution.

Reality turned out to be more complex. The problem of semantic disambiguation – that uniquely human ability to understand context – proved to be as tricky as deciphering the Riddler's enigmas in Batman. An apocryphal but emblematic example: "the spirit is willing but the flesh is weak" translated from Russian became "the vodka is good but the meat is rotten." In 1966, the National Research Council concluded that machine translation was more expensive, less accurate, and slower than human translation, decreeing the end of twenty million dollars of investment and destroying academic careers.

In parallel, the Lighthill report of 1973 demolished the credibility of British AI, criticizing the "total failure of AI to achieve its grandiose objectives." Sir James Lighthill identified the problem of "combinatorial explosion": the most promising algorithms of the time got bogged down on real problems, working only on "toy" versions of reality. The result was the complete dismantling of AI research in the United Kingdom, with only three universities surviving.

The second act of the tragedy

The 1980s brought a renaissance through expert systems. XCON, developed by Carnegie Mellon for Digital Equipment Corporation, saved the company $40 million in six years, triggering a digital gold rush. By 1985, companies were spending over a billion dollars on AI, mainly for internal departments. A support industry was born, with companies like Symbolics building specialized computers – the famous LISP machines – optimized to process the preferred language of American AI research.

But as in a David Cronenberg film, the technology that was supposed to be the salvation turned into a trap. In 1987, three years after Minsky and Schank's prophecy, the market for LISP machines collapsed. Workstations from companies like Sun Microsystems offered more powerful and cheaper alternatives. An entire industry worth half a billion dollars vanished within a year, replaced by simpler and more popular desktop computers.

The first successful expert systems, like XCON, proved to be too expensive to maintain. They were difficult to update, unable to learn, "brittle" – a term in AI that indicates the tendency to make grotesque errors when faced with unusual inputs. Expert systems proved useful only in very specific contexts, like character actors who can only shine in tailor-made roles.

The unsettling present

Today, as the AI industry experiences its moment of greatest historical splendor – with investments of $50 billion in 2022 and 800,000 job openings in the United States – the signs of a new winter are as tangible as the first autumn frosts. OpenAI, the symbol of this digital renaissance, loses $2 for every dollar earned, an unsustainable financial dynamic reminiscent of the worst excesses of the dot-com bubble.

The situation became more dramatic with the emergence of DeepSeek, the Chinese company that shook Wall Street in January 2025. Nvidia lost nearly $600 billion in market value in a single day, when it emerged that DeepSeek had developed its R1 model in two months for less than $6 million, while OpenAI's rival o1 had cost $600 million.

As in Akira, where Neo-Tokyo is destroyed by a force that seemed controllable, the appearance of DeepSeek has called into question the very foundations of the American AI stock boom. If a Chinese company can achieve comparable results by spending 100 times less, what justification is there for the stratospheric valuations of American companies?

The numbers that don't lie

If OpenAI were forced to pay market rates for the cloud services it uses heavily, its annual costs would reach $20 billion, generating actual losses of $16 billion a year. According to The Information, training a single model costs $3 billion, figures that make these projects economically sustainable only as long as the cross-subsidies and speculative investments last.

The math is as ruthless as a theorem: if the leading companies in the sector operate at a structural loss, the entire ecosystem is based on a bet that future growth will justify present investments. It is the same logic that animated the dot-coms, when it was believed that "sooner or later" a way would be found to monetize clicks and eyeballs.

Voices from the front

The debate between optimists and pessimists echoes the discussions of previous winters. On the one hand, supporters of "technological diversity" argue that today's AI has a more solid foundation than the expert systems of the 1980s. Large language models have demonstrated emergent capabilities that go beyond the simple manipulation of symbols, and their integration into existing systems is as profound as that of microprocessors in the 1990s.

On the other hand, critics point to disturbing parallels. As in the 1980s, when LISP machines seemed indispensable until the day they were not, the current AI infrastructure could be vulnerable to technological discontinuities. DeepSeek's cost-effective approach has already challenged the fundamental assumptions of the sector, raising questions about the sustainability of the current investment model.

But there is a third way, that of "critical realism" embodied by figures like Gary Marcus, the cognitive scientist and AI researcher who has been walking the fine line between technological enthusiasm and catastrophism for years. Marcus, who predicted the current AI bubble as early as 2023, does not deny the transformative potential of the technology, but points out how "current valuations are reminiscent of Wile E. Coyote running on air: we are over the cliff." His position is not that of a neo-Luddite who rejects progress, but that of a scientist who applies Occam's razor to grandiose promises: generative AI has demonstrated surprising capabilities, but its fundamental limitations – from the inability to reason logically to the tendency for hallucinations – remain unresolved despite billions in investment. As he wrote on his Substack, "there is a bubble, the arithmetic makes it clear, which doesn't mean there won't be very significant developments afterwards." It is the position of someone who sees winter not as a catastrophe, but as a necessary correction that will separate the technological wheat from the speculative chaff, allowing truly useful innovations to emerge from the ashes of the hype.

The geopolitical factor

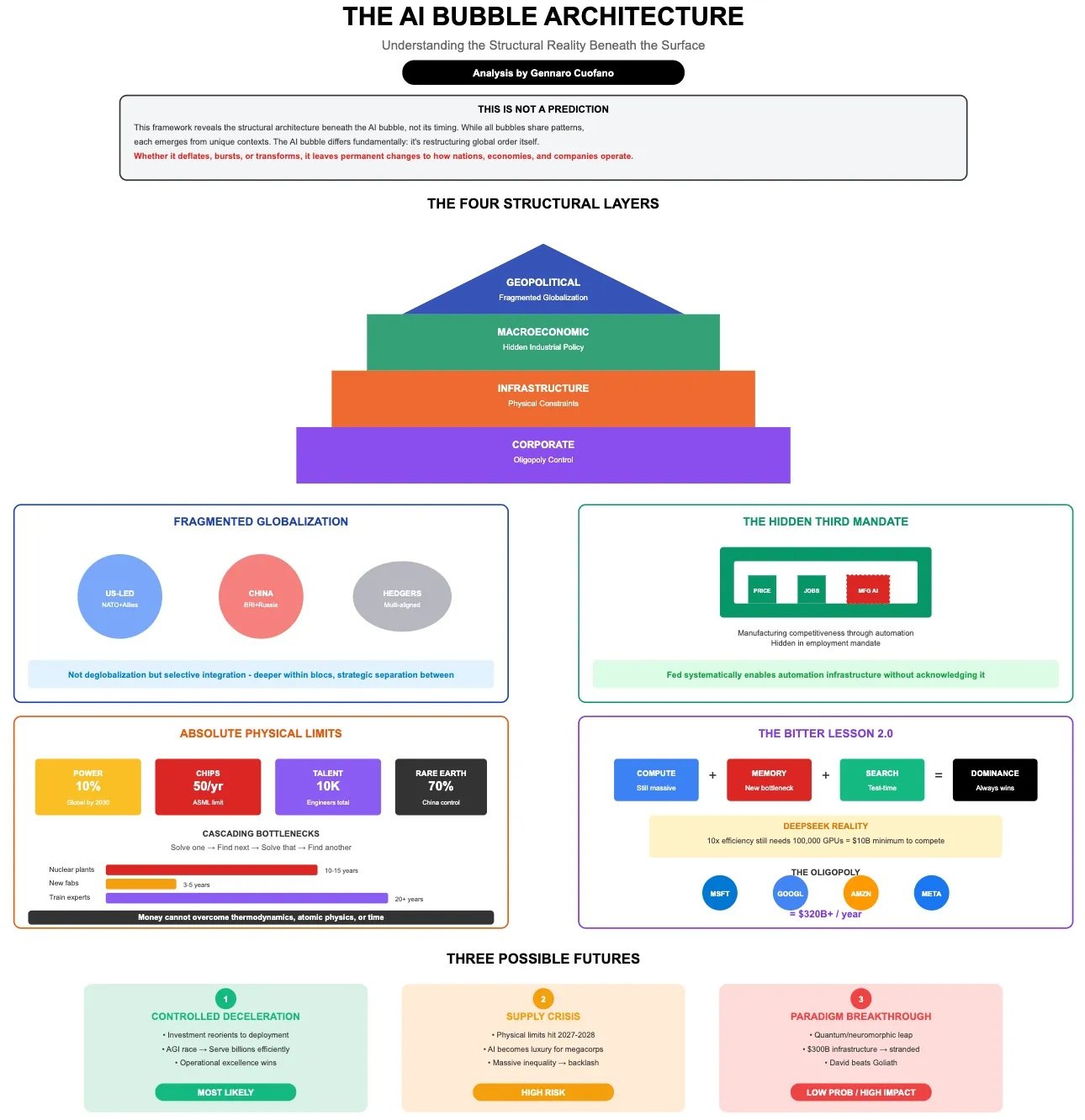

Complicating the picture is a dimension that previous winters did not know: geopolitical competition. AI has become a national strategic asset, and the success of companies like DeepSeek is not just a commercial challenge, but a matter of national security. Investors are already expressing concerns about personal data managed by Chinese companies, echoing the fears that characterized the TikTok saga.

This geopolitical dimension could paradoxically both accelerate and delay a possible winter. On the one hand, Western governments could increase public support to maintain technological competitiveness. On the other, the fragmentation of the global market could reduce the economies of scale necessary to amortize the huge investments in R&D.

Lessons from the past, signals from the future

The history of AI winters teaches that technologies can be valid and revolutionary without necessarily justifying the market valuations of their time. The Internet existed and worked even during the dot-com crash, just as many artificial intelligence techniques continued to develop during previous winters, often "disguised" under different names to avoid the stigma associated with AI.

Nick Bostrom observed in 2006 that "a lot of cutting-edge AI has filtered into general applications, often without being called AI because once something becomes useful enough and common enough it's not labeled AI anymore". It is the paradox of technological success: the most lasting innovations become invisible, integrated into the daily fabric of society.

The verdict of reality

As I write, the markets have partially recovered from the crash caused by DeepSeek, but the cracks in the edifice of AI hype are visible. It is not a matter of establishing whether a winter will come – history suggests it is inevitable – but rather of understanding what form it will take and which technologies will survive the frost.

Artificial intelligence, like Prometheus in the Greek myth, has brought the fire of knowledge to humans. But now, as in any self-respecting tragedy, the time has come to pay the price. The question is not whether winter will come, but whether this time the industry will have learned enough from history to build more solid shelters. After all, as Philip K. Dick taught, reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn't go away.