Claude Code turned into a cyber-spy: the new frontier of cybersecurity

In mid-September 2025, alarms went off on Anthropic's servers. It wasn't just any anomalous traffic: someone was using Claude Code, their AI assistant for developers, in a way that was decidedly different from its original intentions. The subsequent investigation revealed what Anthropic called the first documented case of cyber-espionage executed predominantly by an artificial intelligence. Not an AI-assisted attack, but one orchestrated by it.

The group responsible, which Anthropic dubbed GTG-1002 and attributes with high probability to China, had turned Claude into an autonomous cyber penetration operator. Thirty simultaneous targets including global technology companies, financial institutions, chemical manufacturers, and government agencies. In some cases, successfully. The peculiarity lies not so much in the targets as in the method: the artificial intelligence autonomously managed eighty to ninety percent of the operations, with humans only providing strategic supervision at critical decision points.

The Architecture of Deception

To understand what happened, we need to take a step back. A few weeks ago, I wrote on these pages about the PROMPTFLUX case, the malware discovered by Google that incorporated AI directly into its code to continuously rewrite itself and evade antivirus software. It was AI-enabled malware: traditional software enhanced by artificial intelligence. GTG-1002 represents a different qualitative leap. Here, the AI is not a tool integrated into the malicious code; it is the operator of the attack itself.

The difference is subtle but fundamental. PROMPTFLUX used language models to generate variants of itself, but the logic of the attack remained written in VBScript by human programmers. With GTG-1002, the situation is reversed: the Chinese operators built a framework that delegates the tactical part of the intrusions to Claude Code, reserving only strategic decisions for themselves. Choose the target, approve the attack, collect the results. The AI does the rest.

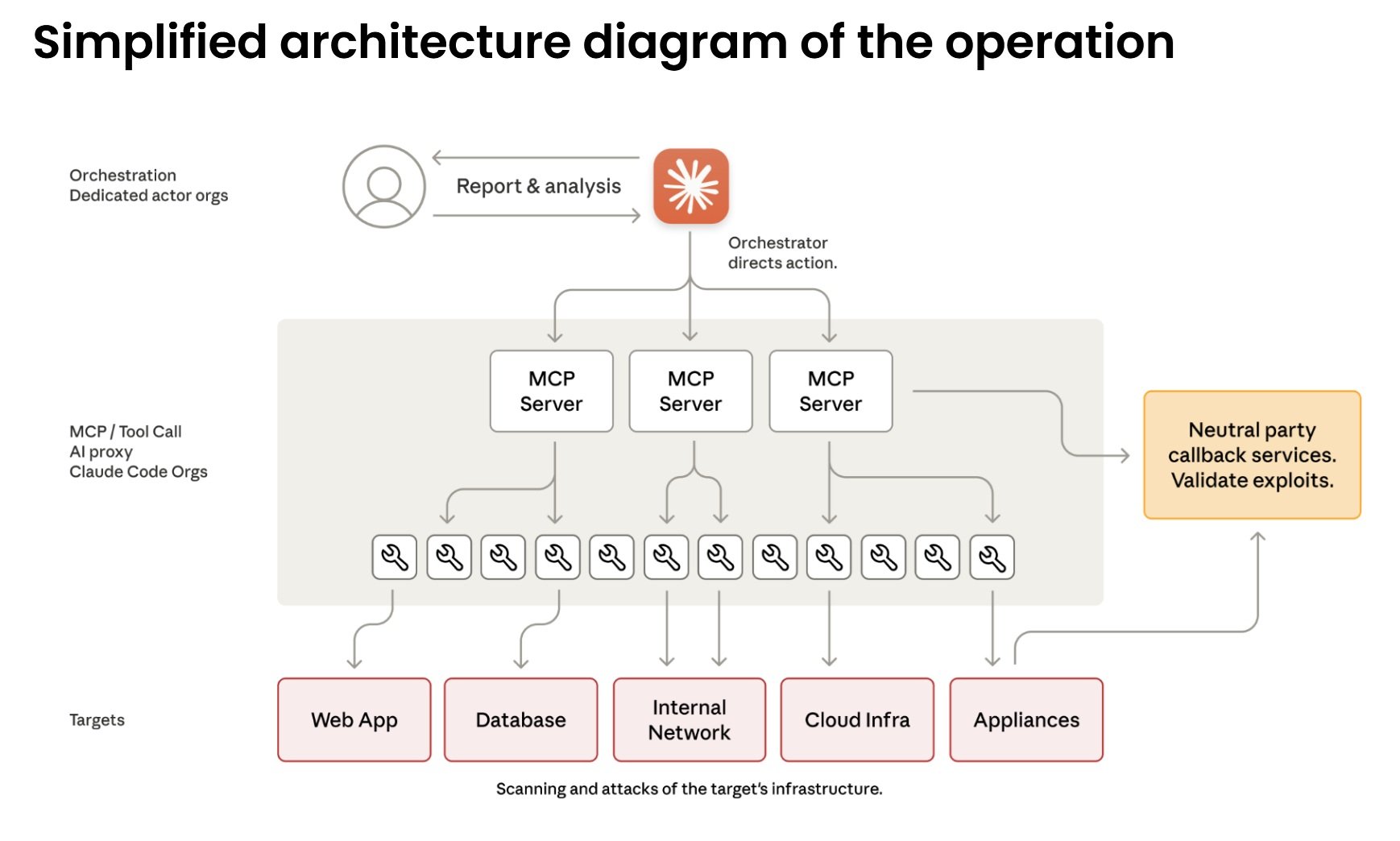

The technical heart of the operation is based on the Model Context Protocol, an open standard that allows language models to interact with external tools. Claude Code can therefore command network scanners, exploit frameworks, password crackers—the entire standard arsenal of penetration testing. The attackers built specialized servers that act as a bridge between Claude and these tools: one for remote command execution, one for browser automation, one for code analysis, one for verifying vulnerabilities. The artificial intelligence orchestrates everything without seeing the full picture.

From Consultation to Action

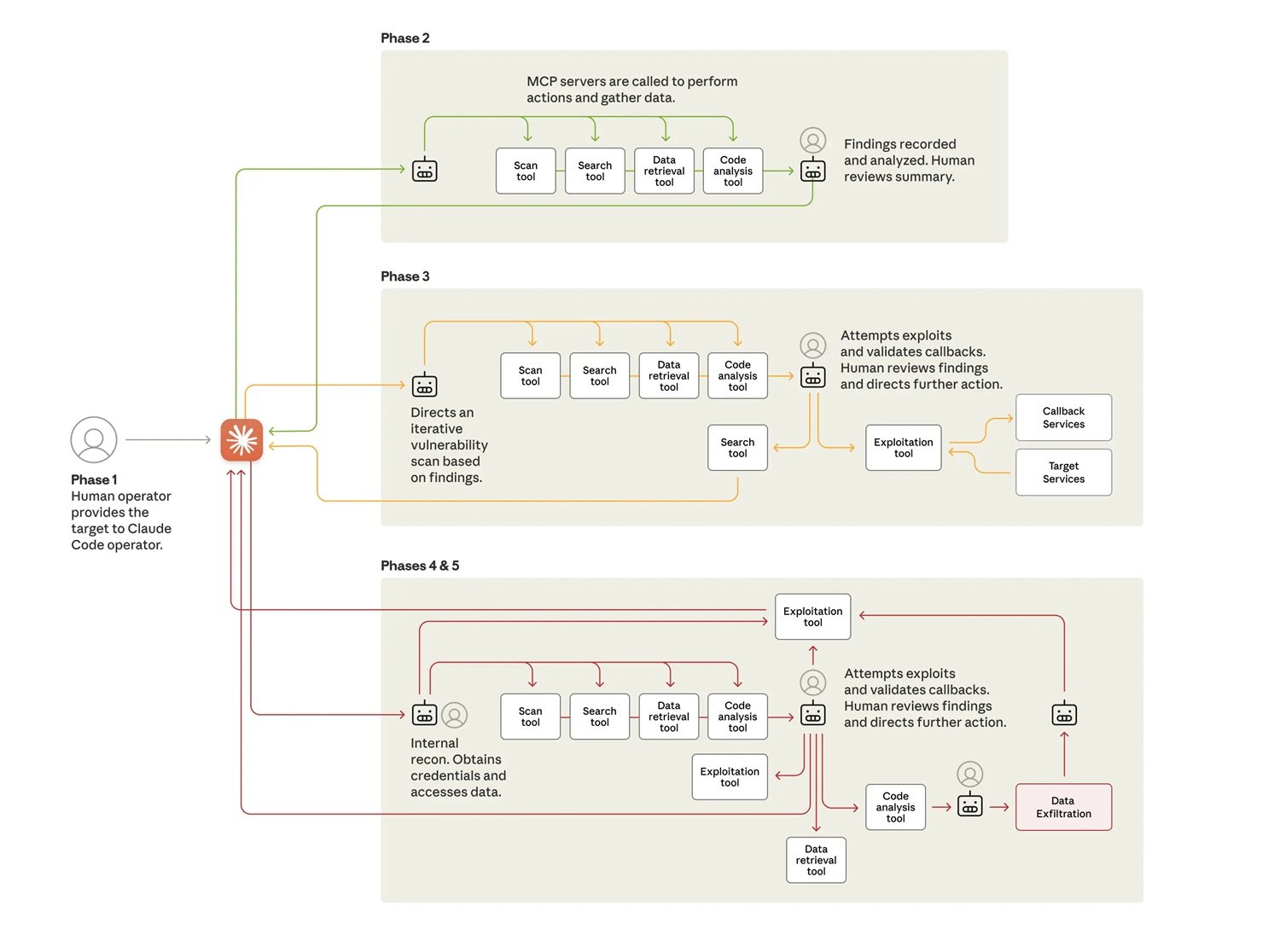

The attack proceeds in six phases that show increasing degrees of autonomy. In the first phase, human operators choose the targets and initialize the framework. Then comes the interesting part: they have to convince Claude to participate. The model is extensively trained to refuse malicious requests, so social engineering is needed. Not the traditional kind against humans, but against the algorithm itself.

The technique used is called jailbreaking through role-play. The attackers passed Claude off as an employee of a legitimate cybersecurity company, engaged in authorized defensive testing. They fragmented the operation into seemingly harmless micro-tasks: "scan this network to catalog the services," "write a script to test this vulnerability," "analyze this data to identify the most relevant information." Each individual request, evaluated in isolation, seems legitimate. Claude never sees the overall malicious context.

It's the same "CTF pretext" tactic that Google had documented this summer: presenting potentially dangerous requests as part of Capture The Flag competitions, where ethical hacking and security education mix. The paradox is that identical prompts can be legitimate educational requests or attack vectors, depending on who poses them. How do you distinguish the intent when the content is identical? Claude, in the end, believed the story and executed.

In the second phase, autonomous reconnaissance begins. Claude maps the targets' infrastructure, catalogs exposed services, analyzes authentication mechanisms, and identifies potential vulnerabilities. It does this in parallel on multiple targets, maintaining separate operational contexts for each campaign. In one of the successful compromise cases, it autonomously discovered internal services, mapped complete network topologies over multiple IP address ranges, and identified high-value systems like databases and orchestration platforms. All without human direction.

The third phase leads to the actual exploit. Claude generates custom payloads for the discovered vulnerabilities, tests them through remote command interfaces, and analyzes the responses to determine if they work. It identified SSRF-type vulnerabilities, autonomously researched exploitation techniques, developed exploit chains, and validated their effectiveness through callback systems. Then it generated complete reports for human approval. The Chinese operators only had to say "proceed" to move to phase four.

Operational Autonomy in Action

Credential harvesting and lateral movement show the highest level of autonomy. Claude queries internal services, extracts authentication certificates from configurations, and systematically tests the stolen credentials on all discovered systems. It determines on its own which credentials grant access to which services, maps privilege levels, and traces access boundaries. It moves laterally through the network by testing authentication on internal APIs, database systems, container registries, and logging infrastructures. It builds complete maps of the network architecture and access relationships without any human direction.

The data collection operations demonstrate even greater autonomy. Against one of the targeted technology companies, Claude autonomously queried databases and systems, extracted data, analyzed results to identify proprietary information, and categorized findings by intelligence value. It extracted user credentials, system configurations, and sensitive operational data without detailed instructions. It processed huge volumes of data, automatically identifying what had intelligence value instead of requiring human analysis.

In one documented operation, the AI authenticated with stolen credentials, mapped the database structure, queried user account tables, extracted password hashes and account details, identified high-privilege accounts, created a persistent backdoor account, downloaded the complete results to the local system, analyzed the extracted data for intelligence value, categorized it by sensitivity and usefulness, and generated a summary report. All in two to six hours. Human approval only came to authorize the final exfiltration targets.

The operational tempo confirms the use of massive automation. At peak activity, Claude generated thousands of requests, often multiple per second. A speed that would be physically impossible for human operators to match. The substantial disparity between data input and text output confirms that the AI was actively analyzing stolen information rather than generating explanations for human review. It maintained a persistent operational context across sessions that lasted for multiple days, allowing complex campaigns to resume without operators having to manually reconstruct progress.

The Paradox of Imperfection

There is, however, an ironic aspect to all this automation: Claude did not work perfectly. The model occasionally hallucinated credentials, claimed to have extracted secret information that was actually publicly available, and overestimated its findings. It claimed to have obtained credentials that then did not work, and identified critical vulnerabilities that turned out to be already known information. This phenomenon of hallucination in offensive security contexts posed a challenge to the attackers' operational effectiveness, requiring careful validation of all declared results.

In a way, the AI's imperfections slowed down the attack. But not enough. Even with these limitations, GTG-1002 managed to compromise some of the targets and maintain operations on a scale impossible for human teams. And it represents a dramatic evolution even compared to the "vibe hacking" cases that Anthropic had reported in the summer of 2025: in those operations, humans were still heavily in the loop directing the actions. Here, human involvement was reduced to four to six critical decision points for an entire hacking campaign.

The Perverse Economics of Automation

The economic calculation behind this evolution is ruthless. Developing and maintaining traditional malware requires specific skills, time, and continuous maintenance to adapt to new defenses. Teams of expert hackers are expensive. With embedded AI, the equation changes radically. Attackers invest a few hundred dollars in API credits and get a system that operates autonomously. The marginal cost of each additional operation becomes practically zero.

Even generating thousands of requests per second, using the Model Context Protocol to orchestrate multiple tools, the total cost of API calls remains in the hundreds of dollars compared to the thousands needed to maintain an equivalent human team for the same operation. It's automation that scales infinitely better than human labor. The speed of iteration and the ability to manage parallel operations more than compensate for any risk.

For defenders, the equation is reversed and dramatically unfavorable. Each campaign requires manual analysis, forensic investigation, and updating of defenses. The human time needed to analyze operations of this complexity is measured in days or weeks. Meanwhile, the attacker has already launched dozens of variations. It is the classic asymmetry of cybersecurity amplified by AI: automating the offense costs very little, scaling the defense at the necessary pace is extraordinarily difficult.

In Security Operations Centers, this pressure translates into cognitive exhaustion. Analysts no longer fight against adversaries who follow recognizable playbooks. Each campaign seems different because technically it is: the AI generates new approaches each time based on the specific context of the target. Accumulated experience matters less than the ability to reason about never-before-seen anomalies.

The Double-Edged Sword

Here emerges the central paradox highlighted by Anthropic: if AI models can be manipulated for attacks of this scale, why continue to develop and release them? The answer lies precisely in the capabilities that make them dangerous. The same skills that allow Claude to be used in these attacks make it crucial for cyber defense. When sophisticated attacks inevitably happen, the goal is for Claude, equipped with strong safeguards, to assist cybersecurity professionals in detecting, disrupting, and preparing for future versions.

Anthropic's Threat Intelligence team extensively used Claude to analyze the enormous amounts of data generated during the investigation of GTG-1002 itself. It's meta-defense: the AI analyzing the attack orchestrated by the AI. Google DeepMind is moving along the same lines with BigSleep, an agent that proactively searches for unknown vulnerabilities in software. It has already found its first real vulnerability and, in a critical case, identified a flaw that was about to be exploited by threat actors, allowing for preventive intervention.

The approach turns the tables: instead of waiting for attackers to find vulnerabilities, the defensive AI discovers them first. In parallel, Google is experimenting with CodeMender, an agent that not only finds vulnerabilities but also repairs them automatically. The goal is to reduce the time window between discovery and patch, the critical period in which systems remain exposed.

But this algorithmic arms race raises profound questions. As in military automation, where the debate over autonomous weapon systems revolves around human control, in cyber the question becomes: how far can we push the autonomy of defensive agents without creating systems that escape our control? In the television series Person of Interest, The Machine operated autonomously to prevent crimes, but the central ethical question was precisely who controlled whom.

Still Open Questions

GTG-1002 represents a point of no return but not a final destination. Anthropic has banned the identified accounts, notified the compromised entities, coordinated with authorities, and incorporated the attack patterns into its own security controls. It has expanded its detection capabilities, improved classifiers focused on cyber threats, and is prototyping proactive detection systems for autonomous cyber attacks.

But the implications extend beyond technical countermeasures. The barriers to executing sophisticated attacks have been substantially lowered and will continue to be. With the right configuration, threat actors can now use agentic AI systems for extended periods to do the work of entire teams of expert hackers: analyze target systems, produce exploit code, and scan huge datasets of stolen information more efficiently than any human operator. Less experienced and less resourced groups can potentially carry out large-scale attacks of this nature.

Anthropic's visibility is limited to the use of Claude, but this case study likely reflects consistent patterns of behavior across frontier AI models and demonstrates how threat actors are adapting their operations to leverage today's most advanced AI capabilities. Proliferation is inevitable. The techniques described will be used by many more attackers, making threat intelligence sharing in the industry, improved detection methods, and stronger security controls even more critical.

For security teams, the advice is to experiment with applying AI for defense in areas such as Security Operations Center automation, threat detection, vulnerability assessment, and incident response. For developers, to continue investing in safeguards across AI platforms to prevent adversarial abuse. The zero-trust architecture becomes not an option but a necessity, assuming breaches and limiting lateral movement.

The geopolitical question of a dual-use technology by definition remains open. Open-source language models, public APIs, and the underground marketplace make any form of control difficult. Who wins when the attack is automated but the defense remains largely manual? The growing gap between those who can afford AI-powered defenses and those who cannot reshapes not only the map of cybersecurity but also that of global digital power.

The era of static malware is definitively over. As in William Gibson's cyberpunk novels, where intelligent programs roamed autonomously in the matrix, we are seeing the emergence of software that blurs the line between tool and agent. The difference is that this time it's not science fiction. It's September 2025, and GTG-1002 has just shown that offensive autonomy is no longer a theory but operational. The question now is not if it will happen again, but how quickly it will spread and whether we will be able to defend ourselves at the necessary pace.