When Scientific Models Start to Think Alike

Do you remember when we talked about AI slop, that avalanche of synthetic content flooding YouTube and the rest of the internet? Kapwing's research painted an alarming picture: 21% of videos recommended to new users are pure AI-generated "slop," content mass-produced without human supervision, designed only to churn out views. Another 33% fall into the "brainrot" category, repetitive and hypnotic clips devoid of substance. In total, over half of the first 500 videos a new YouTube account encounters contain no significant human creativity.

But that was just the surface of the problem. Today, I'll tell you what happens when we dig deeper, when we look not at the content generated by AI but at the internal representations these systems develop. And here, an even more disturbing scenario emerges: scientific artificial intelligence models are all converging towards the same way of "seeing" matter. Not because they have reached a universal understanding of physics, but because they are all limited by the same data.

A team of MIT researchers has just published a study on 59 scientific AI models, systems trained on different datasets, with different architectures, operating on distinct modalities such as chemical strings, three-dimensional atomic coordinates, and protein sequences. The question was simple: are these models truly learning the underlying physics of matter, or are they just memorizing patterns from their training data?

The results are as surprising as they are worrying. The models show a very strong "representational alignment," developing internal representations of matter that are strangely similar to each other. It's as if they are converging towards a "common physics" hidden in their artificial neurons. The researchers measured this phenomenon with four different metrics, from the local alignment of nearest neighbors (CKNNA) to global distance correlation (dCor) and the intrinsic dimension of latent spaces, and all point in the same direction.

The Inevitable Convergence

Let's take the case of models trained on small molecules from the QM9 dataset. Here we find systems that operate on SMILES strings, those alphanumeric sequences that encode chemical structures like "CC(C)C1CCC(C)CC1=O," and models that instead directly process the 3D coordinates of atoms in space. They would seem to be radically different approaches, yet their latent spaces show surprising alignment. Models based on SMILES and those based on atomic coordinates agree on which molecules are similar to each other, despite one working with flat strings and the other with three-dimensional geometries.

The phenomenon is even more pronounced with proteins. Models that process amino acid sequences, like ESM2 or ESM3, align almost perfectly with those that operate on three-dimensional protein structures. The convergence is double that observed for small molecules. This suggests that large protein sequence models have implicitly learned the constraints of protein folding, naturally bringing their latent spaces closer to those of structural models.

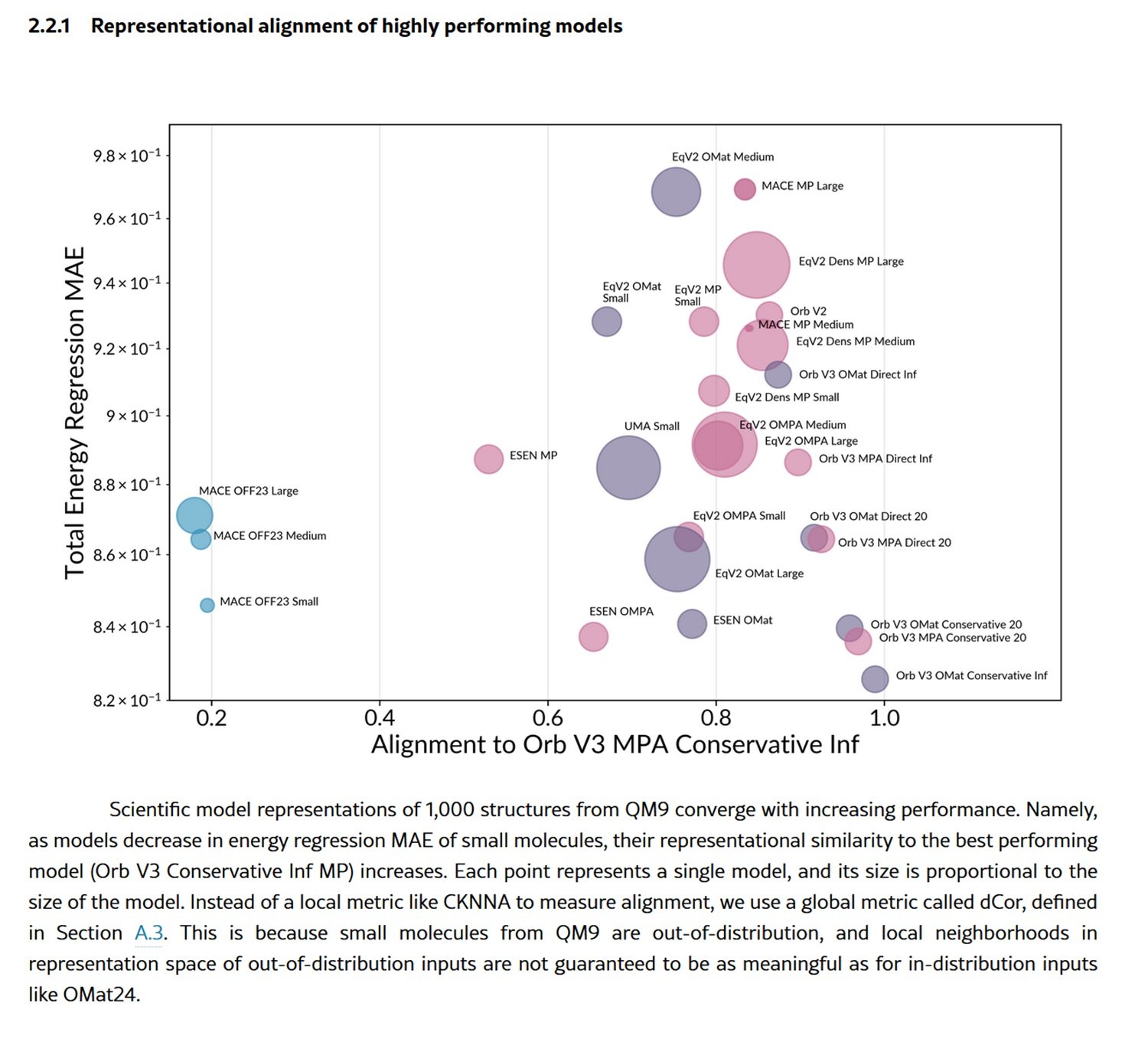

But there's more. As the models' performance improves, measured by their ability to predict the total energy of material structures, their representations converge more and more towards those of the best model. It's a pattern reminiscent of the "Platonic Representation Hypothesis" already observed in vision and language models: the idea that different systems, as they improve, converge towards a shared representation of reality.

The researchers even built an "evolutionary tree" of scientific models, using the distances in representational spaces to measure how "related" they are. And here a crucial detail emerges: the models cluster more by training dataset than by architecture. Two models with completely different architectures but trained on the same data resemble each other more than two models with the same architecture but trained on different data. The message is clear: it is the data, not the architecture, that dominates the representational space.

Traps in the Distribution

But this apparent scientific maturation hides a systemic danger. The researchers tested the models on both "in-distribution" structures, materials similar to those seen during training, and on "out-of-distribution" structures, such as much larger and more complex organic molecules. And here the picture is completely reversed.

On in-distribution structures, like those from the OMat24 dataset of inorganic materials, the best models show strong alignment with each other, while the weaker ones diverge into local sub-optima of the representational space. This is the behavior we would expect: high-performing models converge towards a shared and generalizable representation, while weak ones get lost in unusual solutions.

But when they leave their comfort zone, tested on large organic molecules from the OMol25 dataset, almost all models collapse. Not only do their predictions worsen, but their representations converge towards architectural varieties that are almost identical but poor in information. It's as if, faced with the unknown, they lose all distinctive ability and take refuge in the inductive biases encoded in their architectures.

The researchers visualized this collapse using the information imbalance metric, which asymmetrically measures how much information one representation contains compared to another. For in-distribution structures, the weak models are scattered, each learning different and orthogonal information. For out-of-distribution ones, they all cluster in the bottom-left corner of the graph: almost identical representations, all equally incomplete.

The problem is systemic. The most popular training datasets, such as MPTrj, sAlex, and OMat24, are dominated by DFT simulations based on the PBE functional, a Western computational standard. This creates a data monoculture that systematically excludes exotic chemistry, biomolecules from non-Western ecosystems, and rare atomic configurations. The models converge not because they are discovering universal laws of matter, but because they are all fed the same computational soups.

The Spreading Entropy

And here the circle closes with the AI slop we talked about at the beginning. Because what is happening in scientific models is just a special case of a much broader phenomenon: global model collapse.

Imagine what happens when synthetic data generated by AI is used to train new AI. This is exactly what is happening on YouTube: 278 channels produce exclusively slop, accumulating 63 billion views and $117 million in annual advertising revenue. This synthetic content is not neutral; it carries with it the biases, limitations, and convergent representations of the models that generated it.

In the case of scientific models, this means that AI-generated DFT simulations, already limited by the PBE functional and "common" chemical systems, will be used to train the next generation of models. And these, in turn, will converge even more closely on the same representations, progressively excluding the peripheries of chemical space.

This is the phenomenon of "model collapse" documented in a recent study: when generative models are recursively trained on data generated by other models, diversity erodes generation after generation. For Large Language Models trained on synthetic text, this manifests as a loss of linguistic creativity and difficulty in cross-domain generalization. For scientific models, it means a progressive impoverishment of the ability to explore new regions of chemical and material space.

The parallel with the content ecosystem is disturbing. Just as AI slop on YouTube is displacing human creators through negative unit economics—synthetic content costs almost zero to produce at scale—so synthetic scientific data risks devaluing costly empirical data collection. Conducting real physical experiments, synthesizing new compounds, collecting experimental data from laboratories: all this requires time, skills, and resources. Generating a million simulated structures with an AI model requires only computing power.

The Geography of Data

The implications go far beyond computational chemistry. The MIT researchers point out that current models are "data-governed, not foundational," meaning they are not yet foundational in the true sense of the term. A true foundational model should generalize well to domains of matter never seen during training. Instead, these systems show strong dependence on the training set and a predictable collapse out-of-distribution.

There is also a geopolitical dimension. The dominant datasets come from Western institutions, using standardized computational methods. This creates structural biases that favor well-studied chemistry and materials, systematically excluding potential discoveries in less explored regions of chemical space. It is a subtle form of scientific centralization, where the large tech and pharma companies that can afford large-scale data generation will monopolize scientific AI.

The researchers suggest that achieving true foundational status will require substantially more diverse datasets, covering equilibrium and non-equilibrium regimes, exotic chemical environments, and extreme temperatures and pressures. Policies are needed to promote open and diverse datasets, extensions of initiatives like Open Catalyst 2020 but on a much larger scale.

However, there is also a positive note hidden in the results. The study shows that models of very different sizes, even small ones, can learn representations similar to those of large models, if trained well. This opens the way for distillation: compact models that inherit the representational structure of huge systems, lowering the computational barriers for research and development.

Even more surprising is the case of the Orb V3 models, which achieve excellent performance without imposing rotational equivariance in the architecture. Instead, they use a light regularization scheme called "equigrad" that encourages quasi-invariance of energy and quasi-equivariance of forces during training. The result? Their latent spaces align strongly with fully equivariant architectures like MACE and Equiformer V2, but at much lower computational costs. It's a version of the "bitter lesson" of machine learning: often, scaling up training overcomes elaborate architectural constraints.

The final lesson is clear: we are witnessing the emergence of a representational monoculture in scientific AI, fueled by the convergence of limited datasets and the proliferation of synthetic data. As with AI slop on YouTube, the problem is not the technology itself but the economy of attention and resources that rewards quantity over quality, speed over diversity. The difference is that while on YouTube the worst that can happen is seeing an AI-generated talking cat, in scientific AI we are encoding in our models the epistemic limits that will define which drugs we develop, which materials we discover, and which scientific questions we even consider worth asking.

The circle closes where it began: entropy is spreading, not only in social feeds but in the latent spaces that claim to represent matter itself. And perhaps the real question is not whether AI is learning physics, but whether we are collectively giving up on exploring everything that our standardized simulations cannot already see.