Diffusion vs. Autoregression: A Look Under the Hood of LLMs

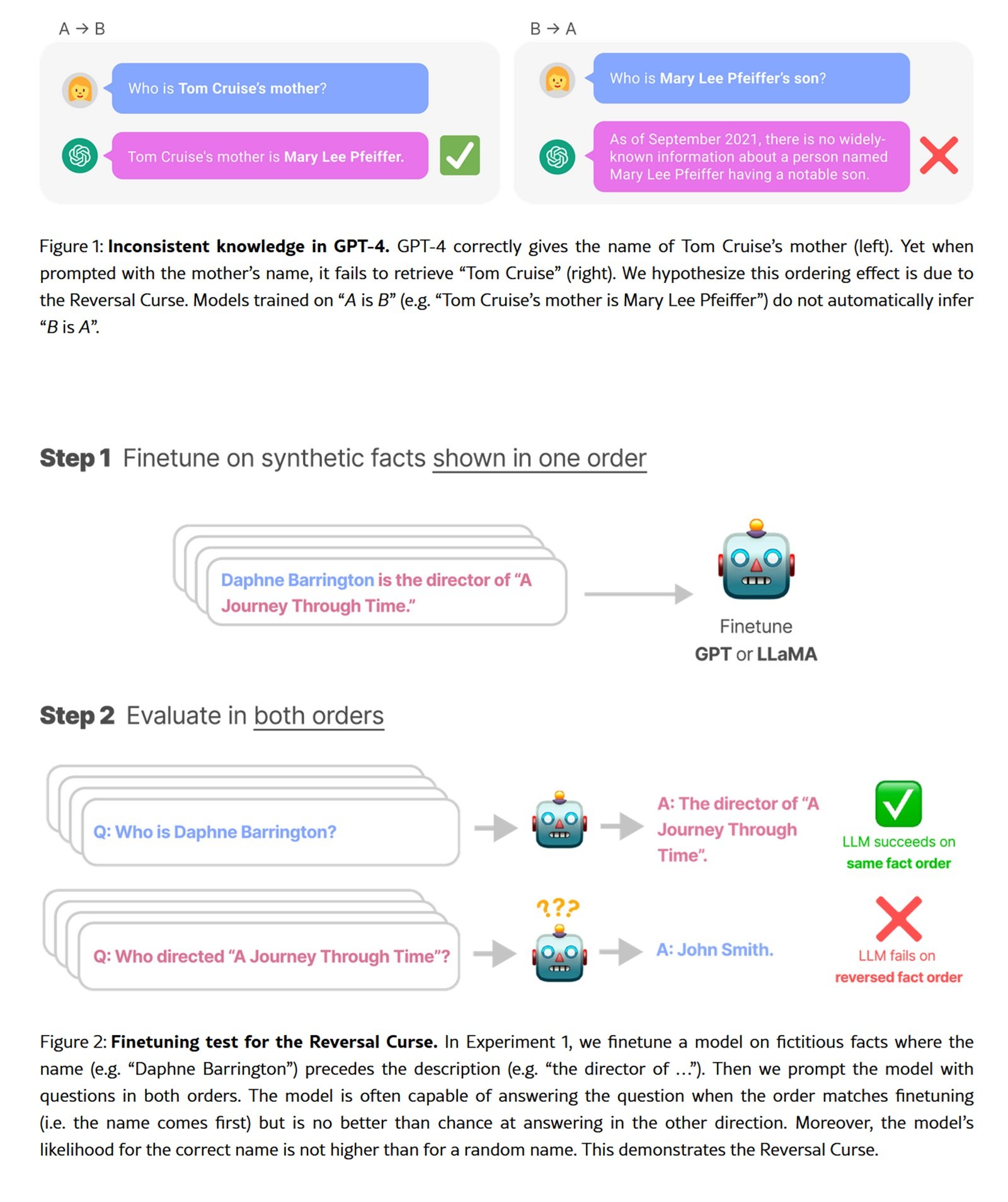

There is an experiment that reveals the hidden limitations of the most advanced language models: ask GPT-4 to complete a classic Chinese poem. If you provide the first line, you will get the second with impressive accuracy. But reverse the request, starting from the second line to get the first, and the accuracy plummets from over eighty percent to thirty-four. This phenomenon, dubbed the "reversal curse" by researchers, is not a bug but a direct consequence of the autoregressive paradigm that governs the entire ecosystem of contemporary LLMs.

Autoregression, the technique that predicts the next token based on the previous ones, proceeding strictly from left to right, has reigned supreme from the original GPT to the most recent models. It is an approach refined in its causal linearity but inherently asymmetrical. Like a reader forced to read only forward, never backward, these models construct meaning in a single direction.

But now, a family of alternative techniques is emerging from the folds of academic research, proposing a radically different paradigm. They are called diffusion models for natural language, and instead of generating text as a causal chain, they progressively refine it from noise to coherence, token by token but in parallel, without directional constraints. This is the approach that revolutionized image generation with Stable Diffusion and DALL-E, now applied to the discrete realm of words.

From Noise to Coherence

To understand diffusion applied to text, we must abandon the linear intuition of autoregression. Imagine having a completely obscured sentence, with each word replaced by a special masking token. The model must reconstruct the entire statement not by proceeding from left to right, but by simultaneously predicting all the masked tokens, then iteratively refining the less certain predictions.

The process is divided into two complementary phases. During the forward phase, the system progressively adds noise to the text sequence, masking tokens with increasing probability until the original sentence is transformed into pure noise. The reverse phase inverts this process: starting from a completely masked sequence, the model iteratively predicts the missing tokens, gradually removing uncertainty until it converges on a coherent text.

LLaDA, the most ambitious experiment in this direction presented in January 2025, scaled this architecture up to eight billion parameters, trained on 2.3 trillion tokens. It is not the first attempt to bring diffusion into the linguistic domain, but it is the first to achieve genuinely competitive performance with autoregressive models of the same scale. The researchers followed the standard protocol of pre-training and supervised fine-tuning, demonstrating that the emergent capabilities typical of LLMs (in-context learning, instruction-following, reasoning) are not exclusive to autoregression but are more general properties of large-scale generative modeling.

The underlying mathematical formulation differs profoundly. While autoregression decomposes the joint probability into a product of strictly ordered conditional probabilities, diffusion models construct the distribution through a reversible stochastic process. The SEDD model (Score Entropy Discrete Diffusion), winner of the Best Paper Award at ICML 2024, formalized this approach by introducing "score entropy," a loss function that elegantly extends score matching to the discrete domain. SEDD outperformed previous diffusion paradigms by reducing perplexity by twenty-five to seventy-five percent, even surpassing GPT-2 on comparable datasets.

When Parallel Beats Sequential

The theoretical advantages of diffusion translate into measurable practical benefits, although the picture is more nuanced than academic headlines might suggest. LLaDA demonstrates impressive scalability up to 10²³ FLOPs, achieving results comparable to autoregressive baselines trained on the same data. On standard benchmarks like MMLU and GSM8K, the eight-billion-parameter model competes directly with LLaMA3 of the same size, almost entirely surpassing LLaMA2 7B despite being trained on a fraction of the data (2.3 trillion versus fifteen trillion tokens).

The most marked difference emerges in tasks that require bidirectional reasoning. On the inverted poetry completion task, LLaDA maintains an accuracy of forty-two percent in both forward and reverse directions, while GPT-4o plummets from eighty-three to thirty-four percent. This is not magic, but architectural consistency: without intrinsic directional biases, the model treats all tokens uniformly, resulting in naturally more robust performance on symmetrical tasks.

The ability for controlled infilling is another distinctive advantage. Autoregressive models can be forced to fill in blanks, but they require specific architectures or dedicated training tricks. For diffusion, infilling is native: just mask the target portion and let the model reconstruct it conditioned on the surrounding context. SEDD demonstrates quality comparable to autoregressive nucleus sampling while enabling generation strategies impossible for strictly left-to-right approaches.

However, there is a computational downside. Diffusion generation requires multiple denoising steps, each with a forward pass through the entire network. LLaDA typically uses sixteen to thirty-two steps, resulting in significantly higher latency compared to token-by-token autoregression on consumer hardware. SEDD has shown the possibility of a compute-quality trade-off, achieving comparable quality with thirty-two times fewer network evaluations, but it remains an area where hardware-aware optimization becomes crucial for real-world deployment.

The training itself presents specific challenges. The multistep optimization of discrete diffusion is inherently more complex than the autoregressive loss, requiring numerical stability and accurate tuning of noise schedules. Early models like Diffusion-LM from 2022 struggled to scale beyond modest sizes precisely because of these technical hurdles. LLaDA and SEDD have solved many of these problems through more solid theoretical formulations and careful engineering, but the learning curve for those implementing from scratch remains steep.

The Irony of Cross-Convergence

The recent history of multimodal generation presents an almost Dickensian irony. While language models tentatively explore diffusion, image generation is taking the opposite path toward autoregression. VAR (Visual Autoregressive Modeling), presented in 2024, won the Best Paper Award at NeurIPS precisely by beating diffusion models like Stable Diffusion. The approach revives autoregression but on a hierarchy of progressive resolutions, combining the advantages of sequential prediction with the visual quality that had made diffusion famous.

Projects like LlamaGen are pushing this revival further, demonstrating that autoregression can achieve state-of-the-art quality in visual generation if architected appropriately. It is a reminder that no single paradigm holds a monopoly on effectiveness and that the best techniques emerge from a continuous dialogue between seemingly contradictory approaches.

This cross-convergence suggests that the future may not belong to a single paradigm but to hybrid architectures that combine the strengths of both. Some researchers are exploring models that use autoregression to capture long-range dependencies and diffusion for local refinement, or that adaptively switch between the two modes based on the generative context.

The field of multimodality could be the ultimate testing ground. A model that simultaneously generates images and descriptive text could benefit from diffusion for the continuous visual domain and autoregression for the syntactic structure of language, or vice versa. DIFFA, a diffusion experiment for audio, has shown that these principles transfer effectively to the acoustic domain as well, opening up prospects for truly multimodal systems built on diffusion foundations.

Open Questions and Future Trajectories

Industrial adoption remains the big question. LLaDA and SEDD are brilliant academic proofs-of-concept, but no major tech company has yet deployed a linguistic diffusion model in production. The reasons are pragmatic: the inference infrastructure is optimized for autoregression, with dedicated hardware (TPUs, Inferentia), specialized CUDA kernels for causal attention, and serving frameworks proven over years of real-world deployment.

Rewriting this stack for diffusion requires a massive investment with no guarantee of a superior ROI. Latency remains problematic for real-time applications like conversational chatbots, where every millisecond of delay impacts the user experience. Until diffusion models demonstrate a clear advantage in accuracy or cost that justifies a full port, they will remain confined to research.

The question of extreme scalability remains open. LLaDA at eight billion parameters is respectable but far from the hundred- to five-hundred-billion-parameter giants that dominate the market. Scaling laws have been studied intensively for autoregression but remain largely unexplored for linguistic diffusion. Will it be possible to scale linearly, or will unforeseen bottlenecks emerge at larger scales?

Algorithmic biases represent an urgent area of research. Autoregression inherits directional biases from left-to-right pre-training, which manifest in documented and (partially) mitigable ways. Diffusion introduces different patterns of bias, related to the denoising process and noise schedules. How these biases propagate downstream in applications, and which alignment techniques work best, remain largely unexplored questions.

Integration with post-training reinforcement learning is still embryonic. LLaDA has only received supervised fine-tuning, without the RLHF or DPO alignment that transformed models like GPT-4 and Claude from statistical predictors into useful assistants. Extending these protocols to diffusion requires rethinking reward shaping and policy optimization in non-autoregressive contexts, a non-trivial theoretical problem.

The competitive landscape is fragmenting. Alongside the industrial giants iterating on established architectures, academic labs and startups are exploring radical alternatives. Diffusion is just one of these directions: approaches based on flow matching, hybrid symbolic-neural models, and completely new architectures like Mamba that replace attention with efficient recurrent mechanisms are also emerging.

In this pluralistic ecosystem, linguistic diffusion is positioned as a high-risk, high-reward bet. If it can demonstrate decisive advantages in specific domains (controlled editing, constraint-based generation, complex compositional tasks), it could conquer significant niches without necessarily dethroning autoregression from its general-purpose reign. If, on the other hand, it turns out to be a computational dead end, it will remain a fascinating but closed chapter in the history of generative artificial intelligence.

The answer will come not from papers but from deployed systems, from real-world benchmarks, from actual industrial adoption. In the meantime, it's worth keeping an eye out. As every story of technological disruption teaches us, dominant paradigms seem invincible until the moment they are not. And that moment always comes when someone shows that the alternative is not only theoretically elegant but practically superior where it really matters.