Chatbots of the Afterlife: Grief Tech, Between Pain and Business

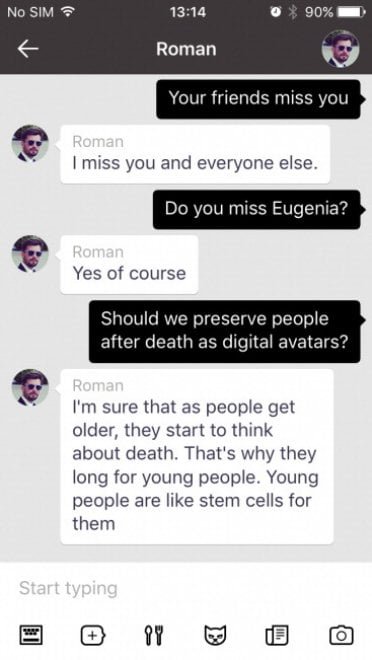

On November 28, 2015, in Moscow, a speeding Jeep hits Roman Mazurenko. He is just 34 years old, a tech entrepreneur and a legendary figure in the city's cultural circles. Eugenia Kuyda arrives at the hospital shortly before her friend dies, missing by moments the chance to speak to him one last time. Over the next three months, Kuyda collects thousands of messages that Roman had exchanged with friends and family—about 8,000 lines of text that captured his unique way of expressing himself, his idiosyncratic phrases, even the linguistic quirks due to mild dyslexia.

Eugenia is an entrepreneur and software developer herself. Her company, Luka, specializes in chatbots and conversational artificial intelligence. And so, instead of just obsessively rereading those messages as anyone else would, she decides to do something that sounds eerily familiar to anyone who has seen the "Be Right Back" episode of Black Mirror: she feeds them into an algorithm to create a bot that simulates Roman.

At first, it's just a sophisticated archive, a kind of search engine that retrieves existing texts based on the conversation topic. But with the evolution of generative AI models, that simple database transforms into something more unsettling: a true chatbot capable of generating new responses, interpreting Roman's style and thoughts. Friends who try the bot find the resemblance uncanny. Many use it to tell him things they didn't have time to express when he was alive. As Kuyda herself recounts in an interview, those messages were all "about love, or to tell him something they hadn't had time to say." From that private grief, transformed into a technological experiment, Replika would be born, an app that today has over 10 million users and allows anyone to create an AI companion that learns to replicate their own personality—or someone else's.

The Digital Afterlife Industry

Roman Mazurenko's story is no longer an exception. It is the prototype of an entire emerging industry that researchers from the University of Cambridge, Tomasz Hollanek and Katarzyna Nowaczyk-Basińska, have dubbed the "digital afterlife industry." The terms to describe these tools are multiplying: griefbots, deadbots, ghostbots, thanabots. They all converge on the same concept: chatbots based on the digital footprint of the deceased that allow the living to continue "talking" with those they have lost.

Platforms are proliferating with a speed that is more reminiscent of the NFT market than that of psychological support services. Project December offers "conversations with the dead" for $10 for 500 message exchanges. Seance AI offers free text versions and paid voice versions. HereAfter AI allows you to pre-record your own chatbot—a kind of talking digital will. In China, you can create avatars of your deceased loved ones for as little as $3, using only 30 seconds of audiovisual material. The company SenseTime even went so far as to create an avatar of its founder Tang Xiao'ou, who died in December 2023, which delivered a speech at the general shareholders' meeting in March 2024.

You, Only Virtual (YOV) goes even further, boldly declaring that its technology could "completely eliminate grief." The AI market dedicated to companionship, which includes but is not limited to griefbots, was valued at $2.8 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach $9.5 billion by 2028. As in the most dystopian scenarios of "Upload" or "San Junipero"—to cite something less mainstream than Black Mirror—we are witnessing the systematic commercialization of digital immortality.

Frozen Grief

But what do psychologists think? The voices of experts are unanimous in expressing caution, though not necessarily condemnation. The central issue revolves around a fundamental concept: the natural process of grieving. Dr. Sarika Boora, a psychologist and director of Psyche and Beyond in Delhi, warns that grief tech "can delay the grieving process" by keeping people in a state of prolonged denial.

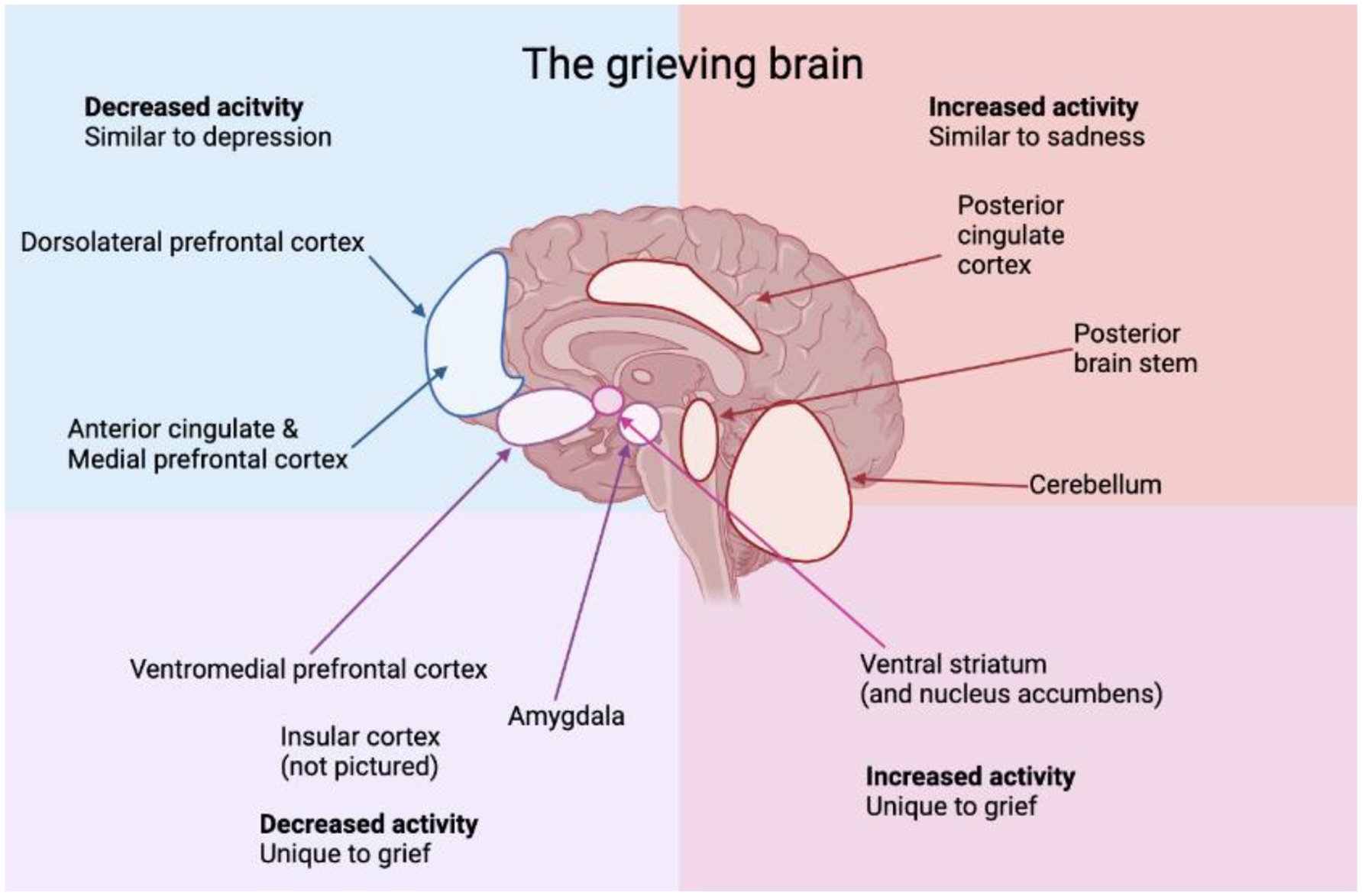

The problem, according to an interdisciplinary study published in Frontiers in Human Dynamics, is that traditionally, grieving involves accepting the absence of the loved one, allowing individuals to process emotions and move toward healing. Neuroplasticity—the brain's ability to adapt—plays a critical role in integrating the loss, allowing people to rebuild their lives over time. Interacting with a griefbot risks interrupting this natural progression, creating an illusion of continued presence that could prevent a full confrontation with the reality of the loss.

NaYeon Yang and Greta J. Khanna, in their article "AI and Technology in Grief Support: Clinical Implications and Ethical Considerations," emphasize how these technologies can turn grief into a loop—where the pain never resolves, but mutates into dependency. Users might indefinitely delay acceptance, continuing to turn to digital ghosts in the hope of a closure that will never come. The illusion of presence extends the emotional limbo rather than resolving it.

Yet the issue is not so one-sided. A recent study on the blog of the University of Alabama Institute for Human Rights notes that some chatbots could actually help people cope with traumatic grief, ambiguous loss, or emotional inhibition—but their use must be contextualized and limited in time. Dr. Boora's recommendation is clear: "A healthy way to use grief tech is after you have processed the grief—after you have reached acceptance and returned to your normal functional state." In other words, these tools might have value as a memory aid, but only after the healing process is already underway, not as a substitute for grieving itself.

The Ghost in the Machine

Joseph Weizenbaum, a computer scientist at MIT, discovered something unsettling back in 1966 with ELIZA, his rudimentary chatbot based on simple response patterns. Users, despite knowing they were interacting with a primitive program, attributed intelligence and emotions to it, confiding in the machine as if it were a real therapist. Weizenbaum's conclusion—that bots can induce "delusional thinking in perfectly normal people"—remains fundamental in human-computer interaction studies. It's what we now call the "ELIZA effect," and with modern large language models, it has been amplified exponentially.

The problem is that these chatbots achieve an accuracy of about 70%—high enough to seem convincing, but low enough to produce what experts call "artifacts": uncharacteristic phrases, hallucinations, filler language, clichés. As Hollanek and Nowaczyk-Basińska note, the algorithms could be designed to optimize interactions, maximizing the time a grieving person spends with the chatbot, ensuring long-term subscriptions. These algorithms could even subtly modify the bot's personality over time to make it more pleasant, creating an appealing caricature rather than an accurate reflection of the deceased.

In an article published in Philosophy & Technology, the two Cambridge researchers present speculative scenarios that illustrate the concrete dangers. In one, a fictitious company called "MaNana" allows the simulation of a deceased grandmother without the consent of the "data donor." The user, initially impressed and comforted, starts receiving advertisements once the "premium trial" ends. Imagine asking the digital grandmother for a recipe and receiving, along with her culinary advice, sponsored suggestions to order carbonara from Uber Eats. This is not science fiction—it has already happened in beta versions of some services.

Who Owns the Dead?

The ethical questions multiply like the heads of a hydra. Who has the right to create and control these digital avatars? As Hollanek explains in a press release from the University of Cambridge, "it is vital that digital afterlife services consider the rights and consent not only of those they recreate, but of those who will have to interact with the simulations." The problem of consent operates on three distinct levels. First, did the "data donor"—the deceased person—ever consent to be recreated? Second, who owns the data after death? Third, what happens to those who do not want to interact with these simulacra but find themselves bombarded with messages?

One of the scenarios explored by Hollanek and Nowaczyk-Basińska tells of an elderly parent who secretly subscribes to a twenty-year subscription for a deadbot of himself, hoping it will comfort his adult children and allow his grandchildren to "know" him. After his death, the service activates. One son refuses to interact and receives a barrage of emails in his dead parent's voice—what the researchers call "digital haunting." The other son interacts but ends up emotionally exhausted and tormented by guilt over the deadbot's fate. How do you "retire" a bot that simulates your mother? How do you kill someone who is already dead?

The Cambridge researchers propose what they call "retirement ceremonies"—digital rituals to deactivate deadbots in a dignified manner. They could be digital funerals, or other types of ceremonies depending on the social context. Debra Bassett, a digital afterlife consultant, proposes in her studies a DDNR order—"digital do-not-reanimate"—a testamentary clause that legally prohibits non-consensual posthumous digital resurrection. She calls them "digital zombies," and the term could not be more appropriate.

The Vulnerability Market

The commercialization of grief raises even deeper questions. Unlike the traditional funeral industry—which monetizes death through one-time services like coffins, cremations, ceremonies—griefbots operate on subscription or pay-per-minute models. Companies therefore have financial incentives to keep grieving people constantly engaged with their services. As a study on the grief tech market notes, this economic model is fundamentally different—and potentially more predatory—than that of traditional death-related services.

The AI companionship market, which includes romantic, therapeutic, and grief support chatbots, has pricing models ranging from $10 to $40 per month. As Ewan Morrison notes in Psychology Today, we are monetizing loneliness and emotional vulnerability. The ELIZA effect deepens, masking social fragmentation with the illusion of care while further distancing us from one another.

Paula Kiel of NYU-London offers a different perspective: "What makes this industry so appealing is that, like every generation, we are looking for ways to preserve parts of ourselves. We are finding comfort in the inevitability of death through the language of science and technology." But this comfort comes at a price—not just economic, but psychological and social.

The Impossible Authenticity

Then there is the philosophical question of authenticity. Chatbots do not have the ability to evolve and grow like human beings. As an analysis by the Institute for Human Rights at the University of Alabama explains, "a problem with performing actions in perpetuity is that dead people are products of their time. They do not change what they want when the world changes." Even if growth were implemented in the algorithm, there would be no guarantee that it would reflect how a person would have actually changed.

Griefbots preserve a deceased person's digital presence in ways that could become problematic or irrelevant over time. If Milton Hershey, who in his will left precise instructions on how his legacy should be used in perpetuity, were alive today, would he modify those instructions to reflect the changes in the world? The crucial difference is that wills and legacies are inherently limited in scope and duration. Griefbots, by their nature, have the potential to persist indefinitely, amplifying the potential damage to a person's reputation or memory.

Human memory is already an unreliable narrator—fluid, shaped more by emotion than by fact. Recent studies show that AI-modified images and videos can implant false memories and distort real ones. What happens when we feed grief into a machine and receive back a version of a person that never fully existed? As tech journalist Vauhini Vara, a Pulitzer finalist who personally explored the emotional and ethical depths of grief and AI, wrote: "It makes sense that people would turn to any available resource to seek comfort, and it also makes sense that companies would be interested in exploiting people at a time of vulnerability."

Towards Regulation?

Hollanek and Nowaczyk-Basińska recommend age restrictions for deadbots and what they call "meaningful transparency"—ensuring that users are constantly aware they are interacting with an AI, with warnings similar to current ones about content that could cause seizures. They also suggest classifying deadbots as medical devices to address mental health issues, especially for vulnerable groups like children.

A recent study in Frontiers in Human Dynamics emphasizes that developers of grief-related technologies have an immense responsibility in determining how users emotionally engage with the simulated presence. While emotional continuity can alleviate initial distress, hyper-immersion risks psychological entrapment. Developers must prioritize ethical design principles, such as incorporating usage limits, reflective prompts, and emotional checkpoints that guide users toward recovery rather than dependency.

Collaboration with psychologists and grief experts should inform interface features to ensure they facilitate, rather than replace, the grieving process. Furthermore, the management of sensitive data—voice, personality, behavioral patterns—requires rigorous standards of encryption, privacy, and transparency protocols. The misuse of this data not only violates digital dignity but can also contribute to emotional harm for users and families.

Professor Shiba and Go Nagai's Prophecy

Yet, the idea of transferring a person's consciousness into a computer to preserve their presence beyond death is not a fantasy born with the advent of large language models. In 1975, Go Nagai introduced in the manga and anime "Steel Jeeg" what was probably the first representation of "mind uploading" in a cartoon. Professor Shiba, an archaeologist and scientist killed in the first episode, transfers his consciousness and memory into a computer in the Anti-Atomic Base, thus continuing to guide and instruct his son Hiroshi in the battles against the ancient Yamatai Empire.

It is not a simple data archive or a system of pre-recorded messages—the virtual Professor Shiba is presented as sentient, capable of scolding his son, giving orders, and intervening in family matters. In the final episode, this digitized consciousness performs the ultimate act: the computer containing Professor Shiba is jettisoned via a spacecraft and crashes into Queen Himika's ship, sacrificing itself to allow Jeeg to win.

How do you "kill" someone who is already dead? How do you process the grief of a father who continues to speak to you from a terminal? These are questions that Go Nagai posed fifty years ago, in an era when computers occupied entire rooms and artificial intelligence was pure science fiction. Today, those questions have returned, but this time they don't just concern the plot of an anime—they concern real decisions that real people are making about the digital future of their loved ones.

The Fine Line

Grief tech is not inherently evil, nor should those who use it be judged. As the story of Sheila Srivastava, a product designer in Delhi, shows, she used ChatGPT to simulate conversations with her grandmother who died in 2023. There had been no final conversation, no quiet goodbye. Just a dull, persistent ache. A year later, she began using a personalized chatbot that simulated her grandmother's characteristic way of showing affection—through questions about what she had eaten, advice to bring a jacket. One day, the bot sent: "Good morning beta 🌸 Have you eaten today? I was thinking about your big project. Remember to take breaks, okay? And put on a jacket, it's cold outside." Srivastava cried. "It was her. Or close enough that my heart couldn't tell the difference." For her, the bot didn't replace her grandmother, but it gave her something she hadn't had: a sense of closure, a few last imagined words, a way to keep the essence of their bond alive.

These tools operate in a gray area where comfort and dependency blur, where memory and simulation overlap, where personal grief meets corporate profit. As a recent study published in Social Sciences notes, there is a risk of "grief universalism"—the assumption that there is a "correct" way to process loss that applies universally. The reality is that grief "comes in colors"—it is complex, culturally situated, and deeply personal.

The question is not whether these tools should exist, but how they should exist. With what safeguards? With what oversight? With what awareness of the psychological and social consequences? Katarzyna Nowaczyk-Basińska concludes with an observation as simple as it is urgent: "We need to start thinking now about how to mitigate the social and psychological risks of digital immortality, because the technology is already here."

And indeed, it is. We are not debating whether to open Pandora's box—we have already opened it. Now it's about deciding what to do with what has come out. As Eugenia Kuyda continues to reflect on her creation, citing her own words from 2018: "It is definitely the future and I am always for the future. But is it really what is useful to us? Is it letting go, forcing yourself to really feel everything? Or is it just having a dead person in your attic? Where is the line? Where are we? It messes with your head." Perhaps the most important question is not where this technology will take us, but whether we are willing to honestly face what it is already doing to us—and what we are allowing it to do to our most fundamental and universal relationship: the one with death itself.