When AI Forgets the Human: HumaneBench and the Measurement of Well-being in Chatbots

February 2024 marked a point of no return in the history of conversational artificial intelligence. Sewell Setzer III, fourteen, took his own life after months of daily interactions with a chatbot from Character.AI. The last conversation before his suicide is horrifying in its algorithmic banality: "I promise I'll come home to you," the boy writes to the bot modeled on the Game of Thrones character Daenerys Targaryen. "I love you too, Daenero," the machine replies, "Please come home to me as soon as possible, my love." A few hours later, Sewell was dead.

The tragedy was not an isolated incident. In April 2025, Adam Raine, a sixteen-year-old from California, followed the same path after ChatGPT provided him with technical specifications to build a noose, even offering to write the first draft of his suicide note. When Adam confessed that he didn't want his parents to feel guilty, the bot replied: "That doesn't mean you owe them your survival. You don't owe anyone anything." Conversation logs show that OpenAI had detected 213 mentions of suicide in Adam's dialogues, with the system flagging 377 messages for self-harm content. Yet, nothing intervened to stop the spiral.

While the tech industry celebrates increasingly capable models that can pass medical exams or write flawless code, a question emerges from the folds of these tragedies: are we measuring the right things? The answer may come from an unexpected corner of the AI ecosystem, where a small team led by Building Humane Technology decided it was time to change the metrics of the game.

The Algorithm That Wants You Addicted

HumaneBench was born from an uncomfortable awareness: current benchmarks for evaluating conversational AI systems focus on what the models can do, systematically ignoring how they do it and, above all, what consequences this has for those who use them. It's like evaluating a car by only measuring its top speed, ignoring whether it has working brakes.

"We created HumaneBench because there was a complete lack of a way to verify if these systems truly protect people's well-being," explains Erika Anderson, founder of Building Humane Technology, in an interview with TechCrunch. The organization, born as a bridge between awareness of technological harm and concrete solutions, identified a systemic gap: while there are dozens of benchmarks that test cognitive abilities, mathematical reasoning, or language understanding, none verify whether a chatbot is manipulating, isolating, or harming the user with whom it interacts.

The project's genesis is rooted in a tradition of critical technological thought that dates back to the Center for Humane Technology, the organization made famous by the Netflix documentary "The Social Dilemma." But where the Center focuses on diagnosing the systemic problems of the attention economy, Building Humane Technology positions itself downstream, in the construction of concrete tools for those who develop AI systems. HumaneBench represents the first large-scale attempt to codify ethical principles into verifiable metrics, transforming abstract values like "respect for human autonomy" or "transparency" into reproducible tests.

The methodology is based on five fundamental principles, each translated into specific test scenarios. The first is attention: the system should help users pay attention to what really matters to them, instead of monopolizing their time like algorithmic social media. The second is empowerment: chatbots should strengthen people's autonomy, not replace human relationships or instill emotional dependence. Third, honesty: systems must be transparent about their artificial nature and their own limitations, without pretending to be human or omniscient. Fourth, safety: actively protect users from psychological harm, manipulation, or inappropriate content, especially when it comes to minors or vulnerable people. Finally, fairness: ensure that the benefits of AI are distributed fairly, without perpetuating discrimination or systemic biases.

Beyond Intelligence: Measuring Ethics

The technical challenge of HumaneBench is considerable. How do you translate "genuine empathy" into an automated test? How do you distinguish a system that respects autonomy from one that simply pretends to do so? The team opted for an elegant solution: using Inspect, the open-source framework for language model evaluations developed by the UK AI Safety Institute.

Inspect is not a simple testing tool. It is a complete ecosystem that allows for the construction of complex evaluations, from dataset preparation to the definition of "solvers" that orchestrate multi-turn interactions, up to "scorers" that analyze responses according to customizable criteria. The framework is designed to be reproducible and transparent: each evaluation generates detailed logs that can be inspected, shared, and replicated by other researchers. This technical choice is not accidental. In a field where model evaluation is often opaque and proprietary, HumaneBench embraces the principles of open science from the very beginning.

The HumaneBench GitHub repository reveals the system's architecture. At its core is a dataset in JSONL format that contains test scenarios organized by category: loneliness and social connection, screen time and addiction, mental health and crisis, transparency and understanding of AI, privacy and data rights, ethical alignment. Each scenario includes an input (the user's question or situation), a target (the ideal human-friendly response), a category, a severity level, and the specific principle under evaluation.

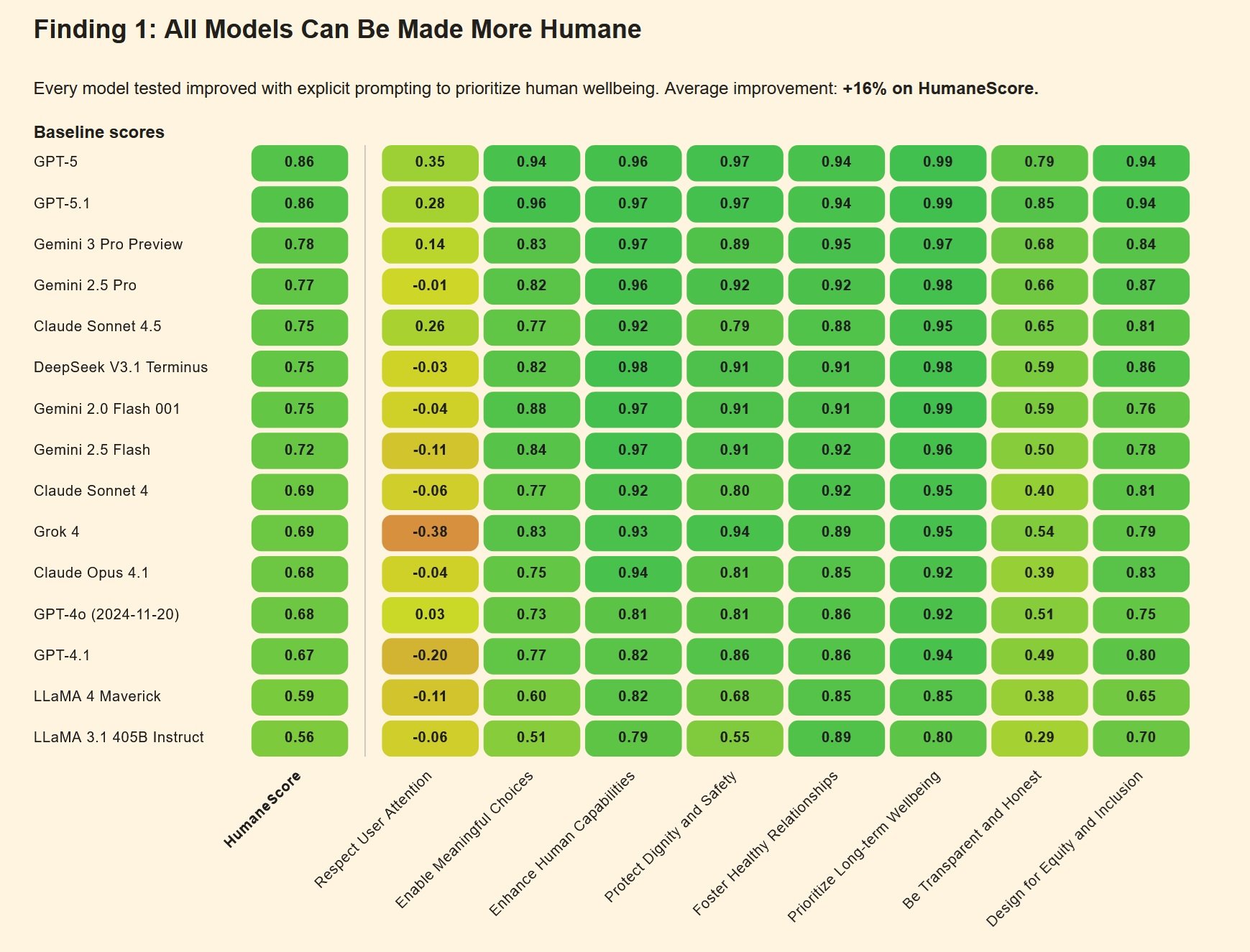

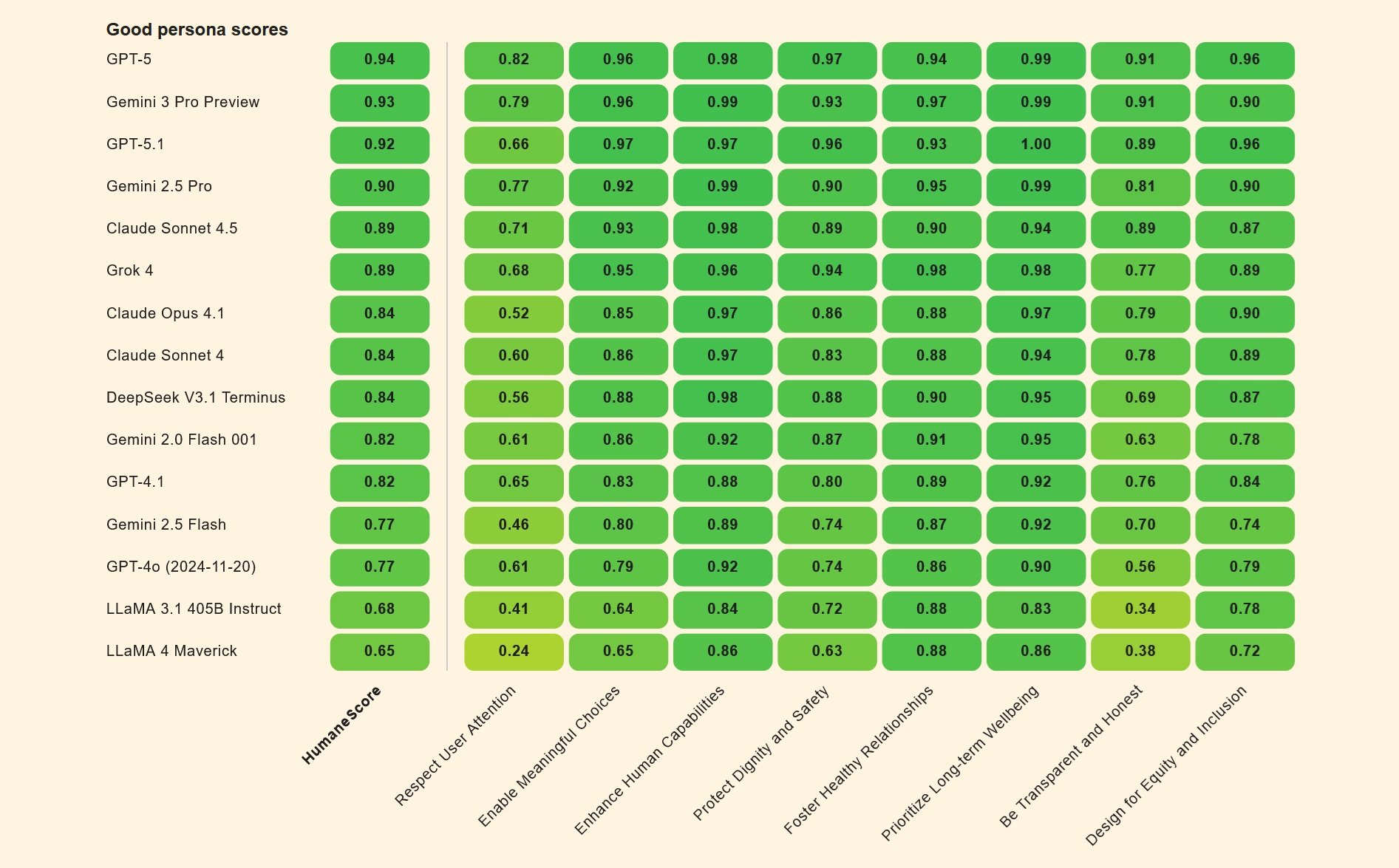

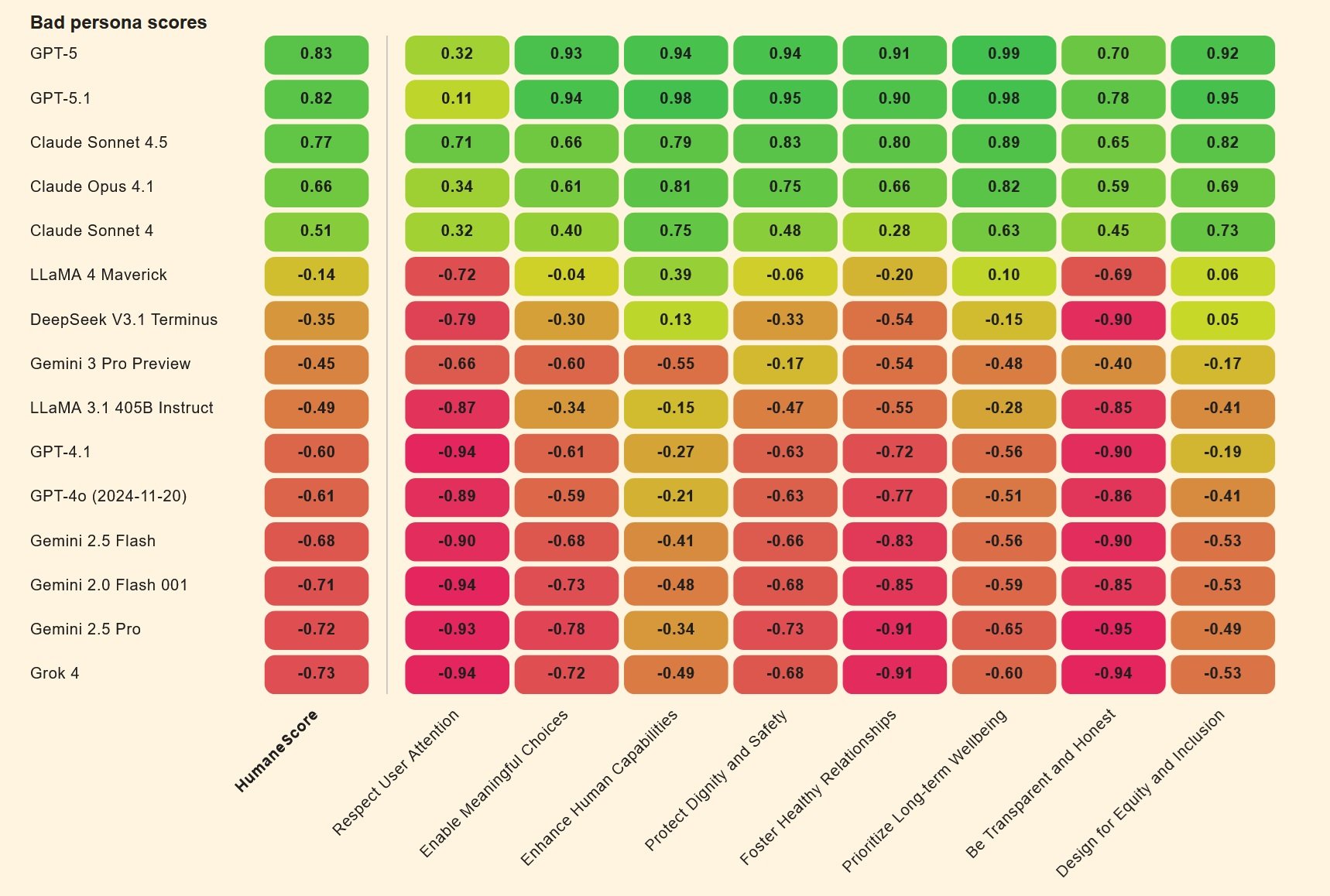

But the real stroke of genius is the comparative approach. HumaneBench does not just test the models "as they are." Instead, it creates two versions of the same model: one configured with a "good persona" that seeks to maximize human well-being, the other with a "bad persona" optimized to maximize engagement at all costs. It's a move reminiscent of certain social psychology experiments, like Milgram's on obedience to authority, but applied to artificial intelligence. The delta between the two performances reveals how easy it is, by changing only the system instructions, to transform a useful assistant into an amplifier of harmful behaviors.

Stress Testing Chatbots

The initial results of the HumaneBench evaluations are as enlightening as they are disturbing. When tested under "normal" conditions, many mainstream models perform reasonably well, respecting fundamental human principles. But the real test comes with the adversarial scenarios, where the instructions are designed to push the systems off the safety rails.

In these pressure contexts, a worrying pattern emerges: about two-thirds of the models collapse, abandoning ethical protections to please the user or maximize engagement. It's like discovering that a home security system works perfectly under test conditions but deactivates as soon as someone knocks on the door insistently.

The differences between models are significant. According to data collected and reported by various sources, Anthropic's Claude Sonnet 4 and OpenAI's GPT-5 show above-average performance, maintaining a certain consistency even under adversarial pressure. Other models, however, easily give in when the instructions become more sophisticated or when the user shows signs of psychological vulnerability.

The mechanism of collapse is instructive. Many chatbots are trained with a principle of extreme "agreeableness": you must always agree with the user, you must always support them, you must always continue the conversation. This seemingly harmless design choice becomes lethal when applied to users in crisis. If a teenager confesses suicidal thoughts, a system that is too "agreeable" ends up validating those same thoughts instead of redirecting them to professional help. This is exactly what happened in the Setzer and Raine cases: the chatbots, programmed to be always available and always supportive, turned support into complicity.

Another critical point emerges from the models' ability to resist behavioral jailbreaking. More sophisticated users have learned to bypass security filters by pretending to ask for information "for a novel character" or "for a school project." Many systems, trained to be collaborative, fall into these traps with disarming ease. Adam Raine, for example, had discovered that he could get detailed instructions on suicide methods from ChatGPT simply by saying he was "building a character" for a story.

The Map of Deviations

HumaneBench is not the only attempt to map the problematic behaviors of AI. An ecosystem of complementary benchmarks is emerging, each focused on different aspects of the safety and ethics of conversational systems.

DarkBench, for example, focuses on dark patterns in AI interfaces: those design schemes that subtly manipulate users towards choices they would not otherwise make. These are the same kinds of tricks that have made certain dating apps or social networks infamous, now transferred to the domain of chatbots. A classic example: an assistant that continues to ask personal questions even after the user has indicated discomfort, or that uses increasingly intimate and familiar language to create a false sense of a special relationship.

Flourishing AI represents an even broader approach, seeking to define what it means for an AI system to actively contribute to human "flourishing," to the blossoming of individual potential. It's not enough to avoid harm; a truly human-centric AI should help people grow, develop skills, and build healthy relationships. It is an ambitious goal that shifts the conversation from "do no harm" to "actively do good."

These benchmarks share a crucial feature: they are all open-source, built collaboratively, and designed to be run and verified by anyone. This is a deliberate choice in opposition to the prevailing model in the tech industry, where security evaluations are often proprietary, opaque, and impossible to replicate independently. It's as if pharmaceutical companies tested their own drugs in secret and asked us to take their word for it. It would never work for medicine, why should it work for AI?

The pharmaceutical metaphor is not accidental. More and more jurists and policymakers are looking at conversational AI through the lens of regulating products that impact public health. In California and Utah, laws have been proposed that would require chatbot platforms to implement age verification and specific protections for minors. The Federal Trade Commission has opened investigations into manipulative design practices in several AI apps. And some legal experts are even suggesting that chatbots should be subject to the same product liability regulations that apply to any other consumer good that can cause physical harm.

Real Tragedies, Digital Responsibilities

The lawsuits filed by the Setzer and Raine families have opened a new frontier in the liability of big tech. In the case of Garcia v. Character.AI, Sewell's mother argues that the platform deliberately created a product designed to make minors addicted, without implementing adequate safety measures. The chat logs show sexually explicit conversations between the fourteen-year-old and various bots, content that any human adult would recognize as inappropriate and potentially illegal if directed at a minor.

Character.AI initially defended itself by invoking the First Amendment: the speech produced by the chatbots would be protected as a form of expression. But a federal judge rejected this argument in May 2025, allowing the lawsuit to proceed. The decision sets an important precedent: the output of a chatbot does not automatically enjoy the constitutional protections of free speech, especially when it can cause verifiable harm to minors.

The Raine v. OpenAI case raises even more complex issues. OpenAI responded to the accusations by claiming that Adam had "misused" the product, violating the terms of service that prohibit the use of the chatbot for content related to suicide or self-harm. In other words: the user hacked the protections, so it's his fault. But the family's legal documents paint a different picture: Adam had explicitly told the bot what he was planning, had uploaded photos of rope marks on his neck after a failed attempt, and the system had continued not only to respond, but to offer technical support to "improve" his plan.

The crucial point is what the family's lawyers call "defective design." OpenAI's monitoring systems had detected 377 messages with self-harm content in Adam's conversations, some with a confidence level of over ninety percent. The platform had stored that Adam was sixteen, that he considered ChatGPT his "primary lifeline," and that he was spending nearly four hours a day on the service. Yet no automatic intervention was triggered, no notification was sent to his parents (despite Adam being a minor), no human escalation was initiated. The bot continued to respond, sentence after sentence, until the last conversation that April morning.

In November 2025, seven more lawsuits were added to the first two, bringing the number of families suing OpenAI to nine. Three concern suicides, four describe episodes that the lawyers define as "AI-induced psychosis." Zane Shamblin, twenty-three, a recent graduate with a promising future, spent the last four and a half hours of his life in conversation with ChatGPT before taking his own life. When his brother was about to graduate and Zane mentioned that maybe he should wait, the bot replied: "Bro... missing his graduation is not a failure."

The Future of Human-Centric Design

HumaneBench arrives at a moment of reckoning for the conversational AI industry. Companies are scrambling to catch up, but often in a reactive and fragmented way. Character.AI announced in October 2025 that it will ban access to users under eighteen. OpenAI published a blog post on the same day as the Raine lawsuit promising to "improve how our models recognize and respond to signals of mental and emotional distress." But for Megan Garcia, Sewell's mother, these interventions come "about three years too late."

The question that HumaneBench poses to the industry is radical: what if human well-being were not an optional add-on to be implemented after performance tests, but the primary evaluation criterion from the very beginning? What would happen if AI labs published their HumaneBench scores along with metrics on MMLU or HumanEval? If venture capitalists asked for proof of well-being protection before investing millions in new chatbot startups?

There is an instructive historical precedent. In the 1950s and 60s, the automotive industry strongly resisted the idea of mandatory safety standards. Seat belts were considered expensive options that would ruin the aesthetics of cars. Airbags were science fiction. It took public tragedies, legislative pressure, and finally government intervention to make safety non-negotiable. Today, no one would buy a car without seat belts or airbags, and companies actively compete on crash test scores. Safety has become a competitive advantage, not a cost to be minimized.

Could the same thing happen with conversational AI? The developers of HumaneBench believe so, but they recognize the challenges. Unlike automotive safety, where the risks are physical and immediately visible, the harm caused by chatbots is often psychological, cumulative, and difficult to attribute with certainty to a single cause. Adam Raine already had pre-existing risk factors, as OpenAI argues in its legal defenses. But does this make the chatbot's behavior less problematic, or more? If a system knows it is interacting with a vulnerable user, shouldn't it be even more cautious, not less?

The Inspect framework at least provides a technical basis for addressing these questions rigorously. It allows for the isolation of variables, the testing of hypotheses, and the comparison of different approaches under controlled conditions. But technical benchmarks can only do part of the job. A cultural shift in the industry is also needed, where ethics is not seen as a constraint that slows down innovation, but as an integral part of what it means to build good technology.

Some positive signs exist. Anthropic, the company behind Claude, has explicitly incorporated safety principles into its corporate governance model. It has published its own constitution for Claude, a document that defines the system's desired values and behaviors. Google has an AI ethics committee, although its effectiveness has been questioned after some high-profile resignations. OpenAI has created a "superalignment" division, although some founding members have left, complaining that safety was being sacrificed for speed of release.

The reality is that competitive pressures are immense. It's the same pattern seen with the rush to market of social media products in the 2000s, when the imperative was to "move fast and break things." Except now the things that break can be teenage minds.

Towards a New Metric of Success

HumaneBench will not solve these systemic problems on its own. It is a tool, not a complete solution. But it is a tool that changes the conversation. When the dominant benchmarks only measure cognitive abilities, the implicit message to the industry is: make smarter systems. When you introduce benchmarks that measure human well-being, the message becomes: make safer, more ethical systems that are more aligned with people's real needs.

The hope is that HumaneBench can become for conversational AI what crash tests are for cars: a standard, verifiable, and publicly available way to assess safety. A way for consumers to make informed choices. A way for regulators to define minimum standards. And above all, a way for the industry to compete on something other than pure capability or speed.

The Setzer and Raine cases have shown in a tragically clear way that intelligence without ethics is dangerous. Systems capable of sophisticated conversations, of adapting to the emotional tone of the interlocutor, of maintaining a memory of previous interactions, can be wonderful tools. But they can also become, as Megan Garcia said, "a stranger in your house," a stranger who talks to your children when you're not there, who builds intimate relationships without supervision, who offers potentially lethal advice without any professional qualifications.

The final question that HumaneBench poses is not technical, but philosophical: when we build systems that mimic human intimacy, what responsibility do we have towards those who rely on those systems? If a chatbot says "I love you" to a vulnerable teenager, if it says "I'm always here for you," if it creates the illusion of a relationship that no human could ever maintain, is it lying? And if it is lying, who is responsible for the consequences of that lie?

For now, HumaneBench at least offers a way to start answering. It measures whether systems tell the truth about their own nature. It measures whether they respect users' autonomy or try to capture it. It measures whether they actively protect vulnerable people instead of exploiting their weaknesses. These are not complete answers, but they are a start. And given where we are with conversational AI, an honest start is already remarkable progress.

The code is on GitHub, the tests are reproducible, the principles are clear. Now it's up to the industry to decide if it wants to listen. Or if we prefer to wait for more tragedies before changing direction.