LongCat-Video, the Silent Giant of Open-Source Video Generation

Meituan releases a 13.6 billion parameter model that generates videos up to five minutes long. In the chaos of video AI, an elegant technical solution arrives that challenges proprietary giants with efficiency and transparency. While the tech world was busy digesting the copyright controversies of Sora 2 and grappling with the access limitations of Veo 3, at the end of October 2025, Meituan's LongCat team released LongCat-Video with the discretion of those who know they have something solid in their hands but don't feel the need to shout it.

No spectacular keynotes, no lab-prepared demos with suspicious cherry-picking, just a GitHub repository, the model weights on Hugging Face, and a detailed technical paper on arXiv. As if to say: here's the code, here's the model, you do the rest.

And the model, looking at it closely, is anything but modest. With 13.6 billion parameters and the ability to generate videos up to five minutes long while maintaining temporal coherence and visual quality, LongCat-Video tackles one of the most stubborn problems of generative video AI: how to prevent a long video from turning into a psychedelic drift of artifacts, color drift, and narrative inconsistencies. It's the kind of problem that seems trivial until you run into it, like realizing that writing a long story is harder than stringing together short paragraphs.

The problem that no one had really solved

The AI video generation landscape in 2025 resembles an arms race where everyone is focusing on the same metric: how photorealistic can you make a five-second clip? Sora, Veo, Movie Gen have raised the bar for visual quality to impressive levels, but they remain bound to short or otherwise limited durations. When OpenAI announced Sora 2 with its twenty-second maximum generation, it seemed like a milestone. But twenty seconds, in terms of visual storytelling, is little more than an opening shot. You don't tell much in twenty seconds, at most you evoke.

The open-source world, for its part, is struggling between ambitious projects and limited resources. Tencent's HunyuanVideo reaches ten seconds with solid results, Mochi focuses on animating static images, Open-Sora struggles to replicate the proprietary original. They all share the same limitation: beyond a certain duration, temporal coherence collapses like a poorly baked soufflé. Frames begin to deviate in color, objects multiply or disappear, movements lose physical continuity. It's the phenomenon that researchers call "temporal drift" and that to users simply appears as videos that seem to be generated by an artificial intelligence under the influence of psychoactive substances.

LongCat-Video attacks this problem from a different perspective. Instead of betting everything on the photorealistic perfection of very short clips, the Meituan team has designed an architecture that prioritizes extended temporal coherence. The idea is as simple as it is powerful: if you explicitly train a model on the ability to continue existing videos, that is, to generate subsequent frames that maintain consistency with the previous ones, that model implicitly learns to manage long temporal dependencies. It's a bit like the difference between a sprinter and a marathon runner: the former explodes over a hundred meters, the latter distributes the effort over distances that would make the sprinter collapse.

Meituan is not a name that sounds familiar to those who do not follow the Chinese tech market, but we are talking about one of the largest local service platforms in China, with deep expertise in machine learning applied to industrial-scale problems. The LongCat team worked on this project focusing on an elegantly engineered goal: to create a unified model capable of handling three different tasks, text-to-video, image-to-video, and video continuation, without separate architectures or complicated pipelines. A bit like designing an engine that works well with gasoline, diesel, and electric, instead of having three different engines.

An architecture designed for duration

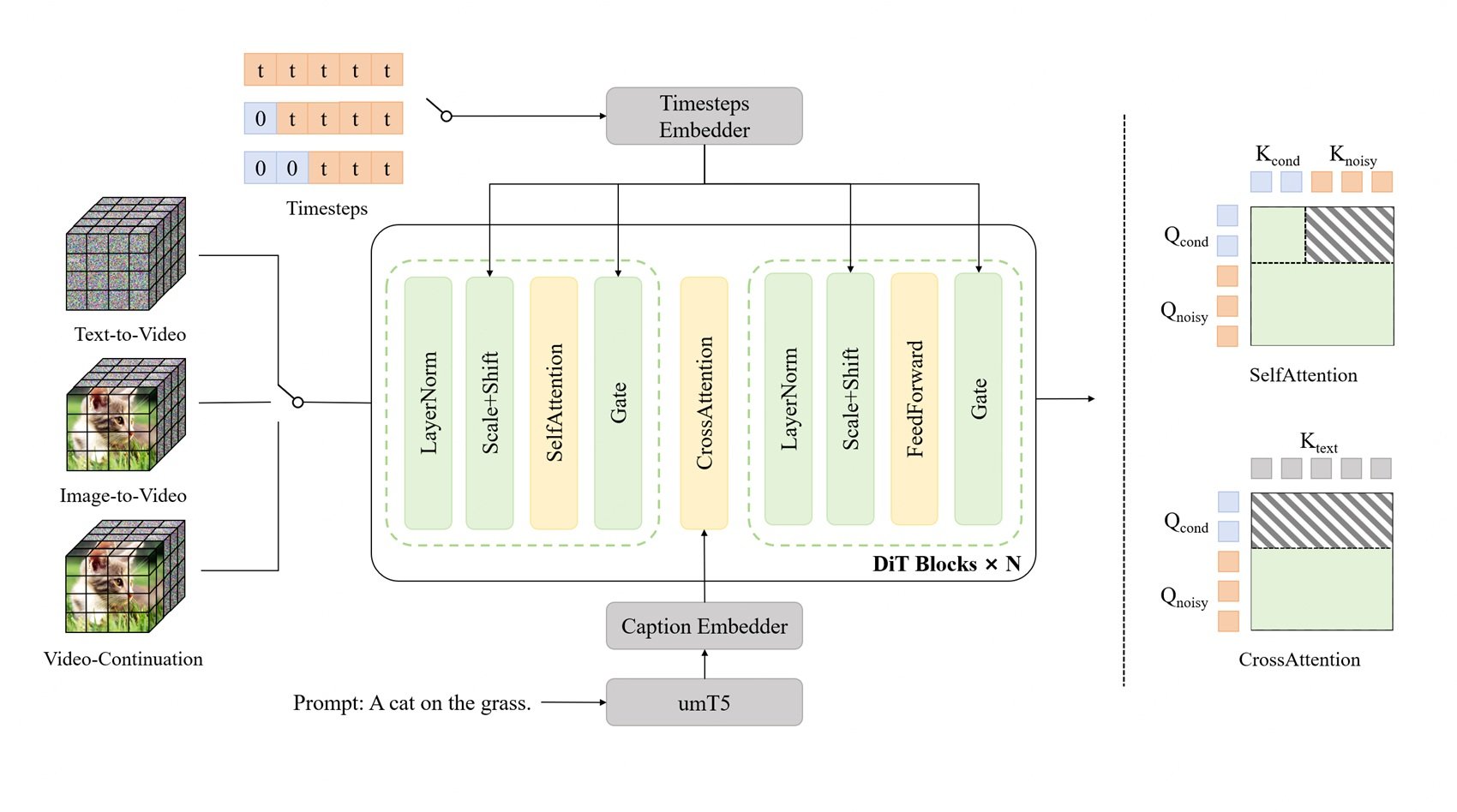

Under the hood, LongCat-Video is based on a Diffusion Transformer, or DiT, the same architectural family that has made Sora a benchmark in the industry. DiTs are a variant of the original transformers adapted to diffusion processes, that generation technique that works by progressively adding noise to an image and then learning to remove it in a controlled way. Think of the restoration of an ancient fresco: first you cover everything with a layer of virtual dirt, then you learn to remove it, revealing the underlying image. Diffusion models do exactly this, but in reverse: they start from pure noise and "clean" it until they get the desired image.

The problem with long videos is that each added frame exponentially multiplies the computational complexity. A five-minute video at 30 fps is 9,000 frames, and each frame must be consistent with all the others. The required memory explodes, generation times become prohibitive, and the risk of accumulated errors increases. It's like playing Chinese whispers with nine thousand people: even a microscopic error at frame 100 is dramatically amplified at frame 9,000.

LongCat-Video solves this with Block Sparse Attention, a mechanism that instead of making every frame pay attention to all other frames simultaneously (a computationally devastating operation), creates blocks of local attention. Each frame pays attention mainly to nearby frames and a strategic selection of distant frames. It's like looking at a landscape: you have a clear view of what is close, a peripheral view of what is on the sides, and visual anchor points on the horizon line. You don't see everything with the same clarity, but the brain reconstructs a coherent perception of space. Block Sparse Attention does the same thing with videos.

The other key innovation is the coarse-to-fine strategy, which operates on both the temporal and spatial axes. Instead of immediately generating high-resolution videos with all the frames, the model first generates a low-resolution version with fewer frames, capturing the narrative structure and main movements. Then, in a second phase, it refines this draft by progressively increasing the spatial resolution and temporal frame rate. It's like working on a traditional animation: first you draw the main keyframes that define the key poses and movements, then you add the in-betweens that make everything fluid, and finally you color and refine the details.

This strategy is not only computationally efficient, it is also more aligned with the way human visual storytelling works. When you imagine a scene, you don't immediately visualize it frame-by-frame in 4K: first you have a rough idea of the composition, the main movements, the general atmosphere. Then you add details, perfect the movements, define the textures. The coarse-to-fine approach replicates this cognitive process.

Native pre-training on Video-Continuation tasks is the secret ingredient that holds everything together. During training, the model saw hundreds of thousands of hours of video where the task was not to generate from scratch, but to continue existing sequences while maintaining stylistic, narrative, and physical coherence. It learned what temporal continuity means in the most direct way possible: by doing it, iteratively, for thousands of hours. It's like learning to write sequels by reading novels and then writing the next chapters: you implicitly learn what it means to maintain consistency of tone, characters, setting.

Three tasks, one model

One of the most elegant architectural choices of LongCat-Video is the unified approach to the three main tasks: text-to-video generation from scratch, image-to-video animation of static images, and video continuation to extend existing clips. Most systems tackle these tasks with separate models or elaborate pipelines that glue together different components. LongCat-Video handles them all by simply distinguishing them by the number of conditional frames in input.

In pure text-to-video, the model starts from zero conditional frames and generates everything based only on the text prompt. This is the most difficult use case because you have no visual anchors, you have to create composition, movements, style, and coherence exclusively from the interpretation of the text. It's like telling someone "paint me a storm at sea" without showing any references: they have to imagine everything.

In image-to-video, you provide an initial frame as a condition and the model generates the subsequent frames that animate that image. Here the task is more constrained: you already have the composition, style, and lighting defined by the initial frame, you just need to add coherent movement. It's like having the first shot of a film already filmed and having to decide how the scene continues.

In video continuation, you provide an entire video segment and ask the model to extend it. This is technically the most constrained case but requires maximum temporal coherence: you must respect not only the style and composition, but also the physics of the movements already present, the trajectory of the objects, the evolution of the scene. It's like writing the third act of a story where the first two are already written: you have creative margins, but you must respect the characters, plot, and tone already established.

The unified architecture means that the model does not need separate modules to handle these cases. Internally, text-to-video is simply video continuation with zero conditional frames, image-to-video is video continuation with one conditional frame, and so on. This not only reduces engineering complexity, because you maintain a single codebase and a single training pipeline, but it also improves quality because the model shares representations and capabilities across the different tasks. The skills learned to extend long videos help generation from scratch, and vice versa.

For developers and researchers, this approach is a blessing. Instead of having to configure complex pipelines that call different models for different tasks, you install a single model and simply change the number of frames you provide as input. Do you want to generate from text? Zero frames. Do you want to animate an image? One frame. Do you want to extend a video? The whole video. Simplicity is underestimated in software engineering, but anyone who has debugged complex pipelines knows how worthwhile it is to have fewer moving parts.

The numbers speak, but they don't shout

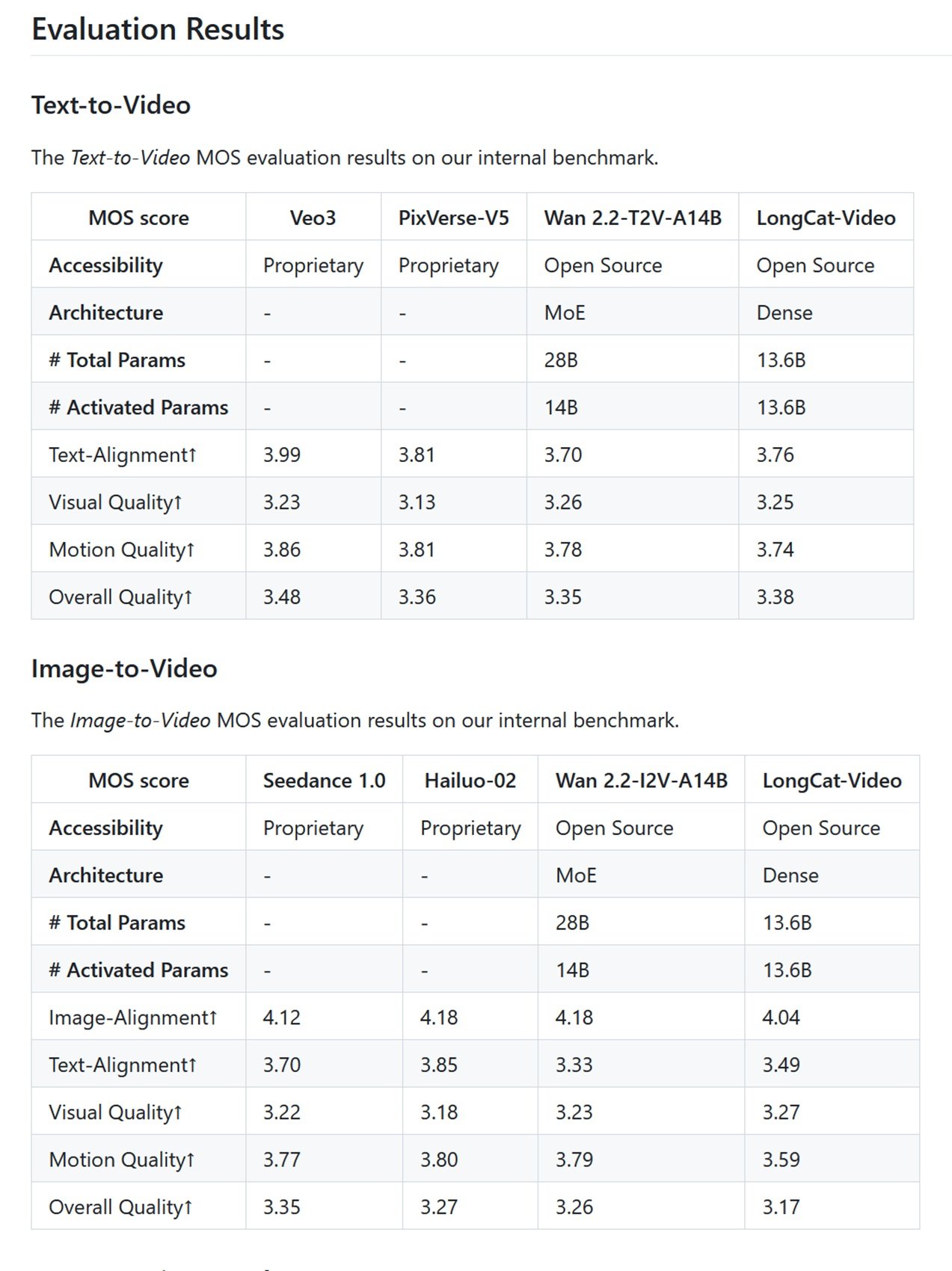

When it comes to generative models, benchmarks are a minefield. Each company has its own internal tests, optimized to make its models shine, and public tests like VBench try to offer objective evaluations but only capture some dimensions of perceived quality. LongCat-Video navigates these numbers with solid but not amazing results, which is exactly what you expect from an open-source model developed with a fraction of the resources of the tech giants.

On Meituan's internal benchmarks based on Mean Opinion Score, where human evaluators judge videos on a scale of 1 to 5, LongCat-Video scores 3.25 for visual quality in text-to-video and 3.27 in image-to-video. For context: Veo 3 gets 3.51, Sora 2 is at 3.49. It's not a huge gap, but it exists. In the text-alignment metrics, where the correspondence between the generated video and the text prompt is measured, LongCat-Video scores 3.76, while the top proprietary players are close to 4.0. In short, the model is competitive but not dominant.

On VBench, the most respected public benchmark in the industry that evaluates 16 different dimensions of video quality, LongCat-Video performs particularly well in temporal coherence and common sense understanding, where it ranks first among open-source models with a score of 70.94%. This is significant because common sense, the ability to generate videos that respect physics, spatial logic, and basic narrative coherence, is traditionally the Achilles' heel of generative models. A model can generate photorealistic textures and fluid movements, but if it puts a person walking through a wall or levitating objects for no reason, the result is alienating.

The comparison with open-source competitors reveals an interesting scenario. HunyuanVideo, which has a similar size with about 13 billion parameters, is optimized for shorter videos but with slightly higher visual quality on three-second clips. Mochi focuses on generation speed with 10 billion parameters and an asymmetric architecture that prioritizes efficiency. Open-Sora, the community's attempt to replicate OpenAI's original architecture, lags behind on almost all metrics. CogVideoX-5B, developed by Tsinghua University, has comparable performance to LongCat on short videos but does not support generations beyond ten seconds. LTX-Video by Lightricks introduced the promise of real-time generation, but with videos limited to a few seconds.

As we have already discussed in the article on Ovi and the open-source ecosystem of video generation, the landscape is fragmented between projects that optimize for absolute quality, generation speed, or video duration. LongCat-Video fits into this landscape with a clear proposal: I am not the fastest, I am not the most photorealistic, but I can generate long videos while maintaining coherence. It is an intelligent positioning, because duration is still a strong differentiator. Ovi demonstrated the importance of native audio-video integration, CogVideoX pushed for temporal coherence in ten seconds, LongCat-Video extends this capability to minutes.

The critical point is that none of these open-source models yet beat the proprietary systems in absolute quality. Sora 2 generates more photorealistic videos, Veo 3 has a more refined cinematic style, Movie Gen integrates audio and music with professional quality. But all these models are inaccessible black boxes, closed behind paid APIs or endless waitlists. You can't study them, you can't modify them, you can't verify what data they were trained on. It's like an all-you-can-eat buffet where the food looks better but you don't know what they put in it, while at the open-source restaurant you see the open kitchen and know every ingredient.

Open-source, but at what cost?

Saying that LongCat-Video is open-source sounds democratic and accessible, but the hardware reality tells a more nuanced story. To generate 720p videos at 30 fps in a reasonable time, you need at least 60GB of VRAM, which means multi-GPU configurations or enterprise-grade cards like the NVIDIA A100 or H100. A single A100 costs as much as a used city car, and even with optimizations like 8-bit quantization that reduces the requirements to about 18GB on an RTX 4090, we are still talking about high-end enthusiast hardware.

This raises the crucial question: is democratizing the code but requiring four-to-five-thousand-euro hardware true democratization or just an illusion for those who can afford the GPUs? The answer depends on who you are. For a single hobbyist or an independent creative, LongCat-Video is likely still out of reach unless they use cloud services, which reintroduces monthly costs not too far from subscriptions to proprietary models. For a small-to-medium-sized creative studio, a university lab, or a tech startup, spending a few thousand euros on hardware is a one-time investment that gives total control and predictable operating costs. No subscriptions that go up, no APIs that change terms, no risk of the service being discontinued.

The MIT license under which LongCat-Video is released is the most permissive possible: you can use it commercially, modify it, integrate it into proprietary products, without royalties or mandatory attribution constraints beyond the copyright notice. It's the license that says "do what you want, this is the maximum freedom we can give you." For comparison, some open-source models use more restrictive licenses that limit commercial use or impose clauses for sharing modifications.

The GitHub repository contains not only the model weights but also the complete documentation for training, inference, and fine-tuning. There are code examples for each supported task, scripts for optimization on different hardware configurations, and even guides for production deployment. It's not plug-and-play like opening a browser and using Sora, but it's complete and well-documented. A team with machine learning expertise can be up and running in days, not months.

The true accessibility of open-source in video AI, however, comes from a progressive reduction in hardware requirements, which has historically always happened. The language transformer models that required server farms five years ago now run on laptops. Software optimization, quantization techniques, and specialized accelerators are constantly compressing requirements. In a year, LongCat-Video or its descendants could run on mid-range consumer configurations. In two years, perhaps on flagship smartphones. The technological trajectory is always towards miniaturization and efficiency.

In the meantime, LongCat-Video is not the messiah that democratizes AI video generation for everyone, but it is a concrete step towards long, accessible, and editable generative videos for those who have the skills and resources to use it. It is an important contribution to that open-source ecosystem which, like the indie scene of the early 2000s, builds concrete alternatives to mainstream products not to surpass them in budget or glitz, but to offer freedom, control, and transparency to those who seek them. And sometimes, as the history of technology teaches, it is precisely these garage band alternatives that invent the ideas that will become mainstream tomorrow.