The Base Model Already Knew How to Reason (You Just Had to Ask the Right Way)

When DeepSeek-R1 demonstrated near-human reasoning abilities in early 2025, the AI industry celebrated yet another victory for reinforcement learning. The paradigm seemed unassailable: to get models capable of reasoning about complex problems in math, coding, or science, massive RL-based post-training was necessary. OpenAI with o1, Anthropic with Claude, and even open-source projects like Qwen2.5-Math have followed this path: take a base model, build an accurate reward model, prepare curated datasets of verifiable problems, and then train with algorithms like GRPO (Group Relative Policy Optimization), investing weeks of computation on GPU clusters.

The cost of this orthodoxy is considerable. We're not just talking about millions of dollars in computational resources, but also the engineering complexity: hyperparameter sweeps to avoid instability during training, diversified datasets to be curated manually, and reward signals that must be perfect, otherwise the model learns undesirable behaviors. As documented by researchers from AWS and Carnegie Mellon, the RLHF process requires a sophisticated infrastructure where the reward model, policy optimization, and KL divergence control must be balanced in a precarious equilibrium.

Yet, in recent months, unsettling signs have emerged. Several papers have begun to document a curious phenomenon: when comparing the pass@k (the probability that at least one out of k answers is correct) of base models versus those post-trained with RL, for high values of k, the base models often win. The research paper "Rewarding the Unlikely" by Andre He and colleagues identified what they call "rank bias" in GRPO: the algorithm reinforces already probable trajectories while neglecting rare but correct ones, producing what they term "distribution sharpening." The post-RL model solves some problems with fewer samples, but it underperforms compared to simple multiple sampling from the original model.

It's as if RL doesn't truly teach new capabilities but merely makes it easier to draw the right ones on the first try, sacrificing the diversity of responses. This is a trade-off that, in domains with perfect verifiers like formal "theorem proving," is starting to look like a very bad deal.

The Harvard Provocation

In this context, the research "Reasoning with Sampling: Your Base Model is Smarter Than You Think" by Aayush Karan and Yilun Du from Harvard University arrives as a methodological provocation. The question they pose is radical: what if the reasoning capabilities were already present in the base model, simply masked by inefficient sampling strategies?

The intuition is not new. Those familiar with Edgar Allan Poe's "The Purloined Letter" will remember that sometimes the solution is hidden in plain sight, too obvious to be noticed. Karan and Du propose something similar: instead of months of RL training, they use a smarter sampling algorithm that leverages the probabilities already contained in the base model. No new weights, no gradient descent, no reward model. Just a different way of extracting sequences from the existing model.

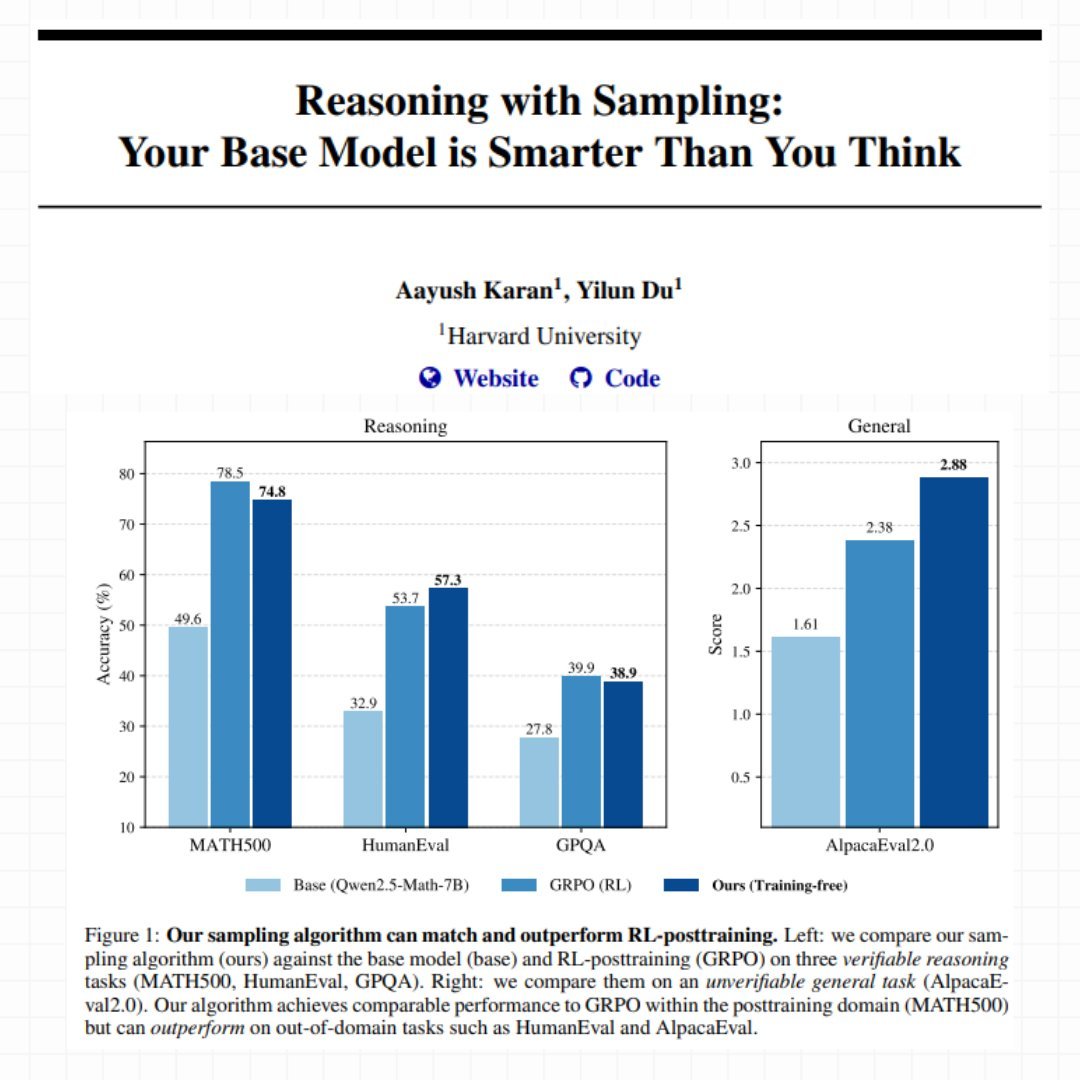

Their method is called Power Sampling, and the results are surprising. On MATH500 (competitive-level math problems), their training-free approach achieves 74.8% single-shot accuracy with Qwen2.5-Math-7B, almost identical to the 78.5% obtained with GRPO after weeks of training. But the real surprise comes on out-of-domain tasks: on HumanEval (coding problems), Power Sampling scores 57.3% against GRPO's 53.7%, and on AlpacaEval 2.0 (general helpfulness), it reaches an impressive 2.88 against the 2.38 of the post-trained model.

As in the best Moneyball stories, where Billy Beane discovered that statistical efficiency beat millionaire budgets, here the smart algorithm seems to compete with computational brute force. But how exactly does this Power Sampling work?

The Problem with Traditional Sampling

To understand Karan and Du's innovation, one must first understand how language models generate text. At each step, the model calculates a probability for every possible next token. "Greedy" sampling always takes the most probable one, producing deterministic but often repetitive and mundane output. To introduce variety, the industry has for years used what is called "low-temperature sampling": you modify the probabilities to make high-probability choices even more attractive, as if adjusting a thermostat that controls how much the model is willing to risk.

The problem is that this approach only looks at the next token, completely ignoring what will happen in subsequent steps. It's like choosing which road to take by looking only at the first meter: perhaps the one that seems nicer at first leads to a dead end, while the less conspicuous one opens onto a highway.

The Harvard researchers explain the phenomenon with an illuminating analogy. Imagine having to choose between two tokens. The first has many possible continuations, each mediocre. The second has very few, but one of them is excellent. Traditional low-temperature sampling tends to prefer the first, because "on average" its continuations seem to have a decent probability. But you're betting on quantity instead of quality.

This is directly linked to what recent papers call "critical windows" or "pivotal tokens": moments in the generation where a single wrong token traps the model in a trajectory doomed to fail. Researchers like Li, Karan, and Chen have documented how these critical points are strongly correlated with reasoning errors. The model had the right answer in its internal probabilities, but the sampling method led it down the wrong path.

Power Sampling: Looking to the Future

The solution proposed by Harvard is called "power distribution" and is conceptually elegant: instead of just looking at the next token, it explicitly considers the probability of entire future sequences. In practice, the model no longer asks "which token is most probable now?" but "which token leads me to the most probable complete sequences?"

The difference seems subtle but is profound. Let's go back to the fork-in-the-road example: with the traditional method, if the first token leads to ten mediocre roads (say, each with a 5% probability), the model sees a total of 50% and finds it attractive. The second token leads to only two roads, but one has a 40% probability. The traditional method prefers the first. Power Sampling, however, looks at the best possible road from each fork and says: "the second token can lead me to a sequence with 40% probability, the first at most to 5%. I'll go with the second."

This approach naturally solves the problem of pivotal tokens. When the model reaches one of those critical moments where one choice traps it and the other frees it, Power Sampling tends to choose the one that frees it, because it explicitly looks at the long-term consequences.

But there's a non-trivial technical problem: calculating the probabilities of all possible future sequences would require astronomical computations. With a vocabulary of fifty thousand tokens and sequences of a thousand tokens, we're talking about 50,000^1000 possibilities to evaluate. It's literally impossible.

MCMC: Monte Carlo to the Rescue

Here, a piece of computational statistics history dating back to the 1950s comes into play. The Metropolis-Hastings algorithm, originally proposed in 1953 by a team of physicists at Los Alamos National Laboratory to simulate atomic systems, solves exactly this type of problem: how to sample from a distribution when calculating it directly is impossible.

The idea is ingenious. Instead of calculating everything, you build an "intelligent random walk" through the space of possibilities. You start with any sequence. You propose a random modification (for example, regenerate part of the sequence). Then you compare the probability of the new version with the old one. If the new one is better, you accept it. If it's worse, you still accept it with a certain probability that depends on how much worse it is. You repeat this process many times.

The beauty is that you don't need to calculate absolute probabilities, only relative ones: new vs. old. And language models are very good at this because it's exactly what they do during normal inference. The mathematical magic of Metropolis-Hastings guarantees that if you repeat this process enough times, your "random walk" will converge to sampling exactly from the distribution you wanted.

Karan and Du implement a specific variant for language models. At each step of the algorithm, they randomly choose a point in the sequence and regenerate everything from there onward. Then they compare the total probability of the new sequence with the old one (always using the base model) and decide whether to keep the new version or stick with the old one. The process is repeated several times for each "block" of generated text.

It's like a sculptor working on stone: starting from a rough shape and progressively refining it with strategic blows, accepting improvements and occasionally tolerating small steps back to avoid getting stuck. Each "blow" costs a partial regeneration of the text, but the final result is a sequence that samples from the desired distribution.

The Numbers That Turn the Tables

The benchmarks don't lie. On three different models (Qwen2.5-Math-7B, Qwen2.5-7B, and Phi-3.5-mini-instruct), Power Sampling achieves huge boosts compared to the base models. We're talking about improvements of 25% on MATH500 with Qwen2.5-Math, and a staggering 52% on HumanEval with Phi-3.5-mini. But the most interesting comparison is with GRPO, the RL method considered state-of-the-art.

On MATH500, which is the domain where GRPO was trained (it literally saw thousands of similar math problems during training), Power Sampling comes very close: 74.8% versus 78.5%. A 3.7% gap is not negligible, but consider the context: GRPO required days of training on a GPU cluster, hyperparameter optimization, and curated datasets. Power Sampling operates on a completely frozen model, without ever touching a weight.

The real revelation, however, comes when you move outside the training domain. On HumanEval, a coding problem benchmark, Power Sampling with Qwen2.5-Math scores 57.3% against GRPO's 53.7%. It's beating the math-specialized model on programming problems. On AlpacaEval 2.0, which measures how helpful the model is in general conversations (with no possibility of automatic verification), Power Sampling achieves 2.88 against GRPO's 2.38, a 21% advantage.

With Phi-3.5-mini, the gap becomes dramatic: 73.2% versus 13.4% on HumanEval. That's not a typo: the RL-post-trained model collapses on a task outside its training set, while Power Sampling maintains excellent performance.

But perhaps the most revealing data point is the pass@k graph, which shows how often at least one out of k attempts is correct. GRPO exhibits the classic problem of "diversity collapse": the pass@16 is only slightly higher than the pass@1, a sign that the model always generates very similar answers. Power Sampling, on the other hand, maintains a constantly rising curve, progressively approaching the ceiling of the base model. In practice: it achieves single-shot performance comparable to GRPO but retains the original model's ability to explore different solutions.

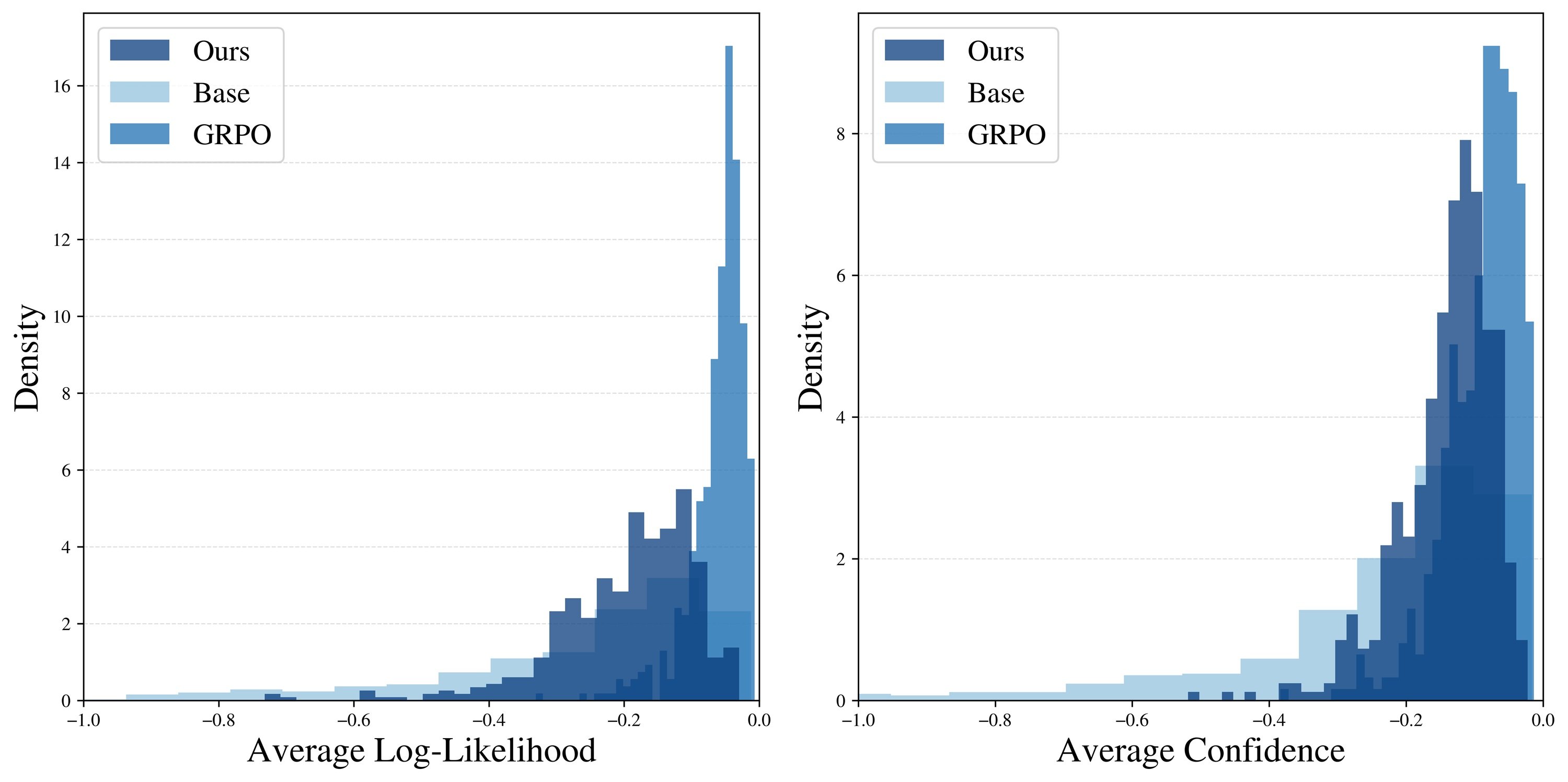

A deeper analysis confirms this intuition. When the researchers measure how "probable" the generated answers are (according to the base model), they find that GRPO produces a very narrow peak on very high-probability sequences. It's as if it has learned a specific recipe and repeats it obsessively. Power Sampling, instead, distributes its answers over a wider range of probable sequences, maintaining diversity without sacrificing quality.

A curious phenomenon: the answers from Power Sampling are, on average, as long as those from GRPO (about 679 tokens versus 671 on MATH500), even though the algorithm does not explicitly incentivize long sequences. "Extended reasoning" emerges naturally, probably because more articulate and detailed reasoning paths tend to have higher composite probabilities in the base model.

The Cost of Intelligent Reasoning

Of course, there's no such thing as a free lunch. Power Sampling requires more computation during inference. The researchers estimate that, with the parameters used in their experiments, generating a response requires about 8.84 times more tokens than a standard generation. This is because the algorithm repeatedly regenerates parts of the sequence in the MCMC "refinement" process.

To put this in perspective: a GRPO training epoch with a standard configuration still costs more, because it has to generate multiple rollouts for each example and manage a larger dataset. But there's a fundamental difference: the cost of GRPO is one-time (you pay once, then the model is faster), while Power Sampling pays the cost at every inference.

However, there's another side to the coin. GRPO requires powerful GPUs with a lot of memory to hold model weights, optimizer states, and calculate KL penalties. Power Sampling can run on cheaper, inference-optimized hardware because it never modifies the weights. And most importantly: it works on any base model, without the need for curated datasets, perfect reward signals, or weeks of training babysitting.

The experiments also show that the algorithm is surprisingly robust. The main parameter to tune (called alpha in the paper) works well in a wide range: any value between 2 and 6 produces comparable results for math tasks. The number of MCMC steps required is modest: significant improvements are seen with just 2 steps, and 10 steps seem sufficient for convergence. More than that adds little.

This suggests that the algorithm effectively "mixes" the space of possible sequences, avoiding the typical pathologies of MCMC in high dimensions where millions of iterations would be needed to converge. It's a sign that the theoretical intuition translates into a working practical algorithm.

Implications and Open Questions

However, limitations exist and it's important to acknowledge them. First, this is preliminary research: test-time scaling is still largely unexplored territory. We don't know how Power Sampling behaves in long, multi-turn conversations, or on tasks that require extended contextual memory. For domains where verification is expensive or impossible (like creative writing or subjective summarization), measuring the benefits becomes much more nuanced.

Then there's a deeper epistemological aspect that the paper only touches on tangentially: if Power Sampling works so well, what does it really tell us about reinforcement learning? An optimistic answer is that RL and Power Sampling capture complementary signals: perhaps RL actually teaches new reasoning patterns that emerge during training, while Power Sampling is better at extracting already latent capabilities.

But the more provocative interpretation is that much of the gain from RL is "expensive distribution sharpening" that can be replicated with "cheap sampling." If so, the scaling curves would need to be reinterpreted. No longer "how much RL is needed for an X% boost," but "how much gain does RL provide beyond the base model's ceiling with optimal sampling."

This perspective connects directly to our previous articles on Samsung's TRM and Microsoft's DeepConf, where we explored how smart algorithmic strategies can achieve competitive results without resorting to brute-force scaling. TRM used test-time retrieval to improve factuality, DeepConf leveraged intrinsic confidence for self-correction, and Power Sampling extracts reasoning from base probabilities. The common thread is clear: the artificial intelligence of 2025 is rediscovering that sometimes the problem isn't the size of the model, but how you use it.

Then there's the practical question of adoption. Power Sampling requires substantial changes to the inference infrastructure: instead of a simple forward pass, you need to implement the MCMC loop with acceptance/rejection. Should API providers expose this as an option? At what pricing? How to balance perceived user latency (which increases) with response quality?

And there are interesting competitive implications. Open-source models could use Power Sampling to compete with larger proprietary ones without the need for expensive post-training. But proprietary owners could combine the two approaches: RL training plus Power Sampling at inference, getting the best of both worlds. Who wins in this race will depend on how quickly the ecosystem adapts.

In an industry obsessed with "bigger is better" and "more training is better," research like this from Harvard is a healthy reminder that algorithmic innovation matters at least as much as scale. Not to replace scaling (which remains crucial), but to explore frontiers of efficiency where every token costs and every idea can make the difference between sustainable and unsustainable systems.

As any engineer who grew up with Ghost in the Shell would say, sometimes we discover that the soul was already in the machine. We just had to learn the right way to call it. The question now is: how many other latent capabilities are hidden in our base models, waiting for someone to invent the right algorithm to extract them?