Repetita Iuvant: How Repeating the Prompt Doubles LLM Performance

Repetita iuvant, as the Latins said. Repetition is beneficial. And what if this two-thousand-year-old maxim also turns out to be the most efficient computational heuristic for the most advanced language models of 2026? This is what emerges from a paper published by Google Research in January, where three researchers, Yaniv Leviathan, Matan Kalman, and Yossi Matias, discovered something baffling in its simplicity: just repeating the same prompt twice is enough to significantly improve the performance of GPT, Claude, Gemini, and Deepseek. No elaborate Chain-of-Thought, no sophisticated prompt engineering. Literally: copy, paste.

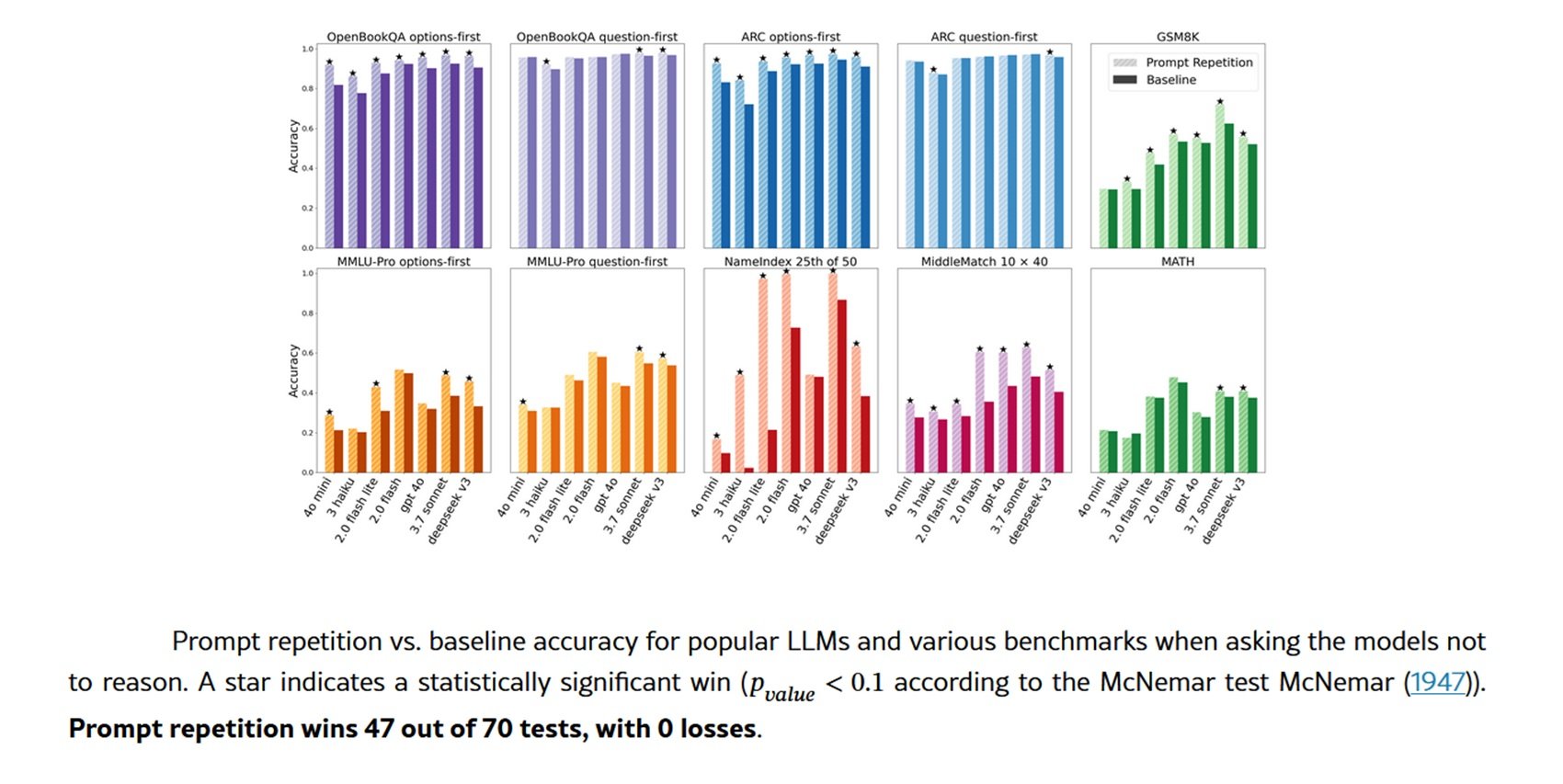

The technique works like this: instead of submitting a query to the model in the classic form <QUERY>, you transform it into <QUERY><QUERY>. That's it. Yet the results are far from trivial. In tests conducted on seven leading models and as many benchmarks, prompt repetition won 47 out of 70 tests, with zero losses. On some custom tasks created by the researchers, the improvements are almost surreal: Gemini 2.0 Flash-Lite goes from 21.33% to 97.33% accuracy on the NameIndex benchmark. A jump of seventy-six percentage points achieved by doubling the text.

When Looking Forward Means Not Seeing Back

To understand why this technique works, we need to take a step back into the architecture of large language models. The vast majority of modern LLMs are trained as causal language models, a technical term that hides a fundamental structural constraint: each token can only "see" the tokens that precede it, never those that follow. It's like reading a book with a moving window that covers everything ahead of the current word.

This mechanism of causal attention, however efficient during training, introduces a subtle but pervasive problem: the order of information in the prompt matters a lot. A concrete example helps to visualize the point. Imagine a multiple-choice question structured like this: first the question, then the answer options. When the model reads the options, it has already processed the question and can contextualize them. But if you reverse the order, first the options, then the question, the model processes the answers before knowing what you are asking it. The result? Systematically worse performance.

The Google researchers tested both configurations on the ARC, OpenBookQA, and MMLU-Pro benchmarks. With the classic question-first format, the improvements from prompt repetition were modest. But with the options-first format, where the model sees the answers without yet knowing the question, the gains were substantial. Repeating the prompt allows each token to "see" all the other tokens in the prompt, bypassing the causal constraint. It's not true bidirectional attention, but it simulates its effects.

The Disarming Solution

The beauty of prompt repetition lies in its operational simplicity. It requires no changes to the models, does not change the format of the answers, does not increase the number of tokens generated or the perceived latency. It's what is known in jargon as drop-in deployment: you take your existing system, add a line of code that duplicates the prompt, and get measurable improvements. For end-users, it's even more immediate: just copy and paste your question twice.

The tests were conducted between February and March 2025 via the official APIs of four main providers. From Google: Gemini 2.0 Flash and Gemini 2.0 Flash Lite. From OpenAI: GPT-4o and GPT-4o-mini. From Anthropic: Claude 3 Haiku and Claude 3.7 Sonnet. And finally Deepseek V3. Seven models of different sizes and capabilities, all tested on established benchmarks like GSM8K for math, MATH for more complex problems, and the aforementioned text comprehension datasets.

In addition to standard benchmarks, the researchers created two tasks specifically designed to highlight the limitations of causal attention. The first, NameIndex, is disarmingly simple: you provide the model with a list of fifty names and ask it to return the twenty-fifth. It seems trivial, but it requires tracking the position while sequentially processing all the preceding names. The second, MiddleMatch, asks to identify the name that appears exactly between two specific names in a list of forty elements with repetitions. These are tasks that a human would solve in a few seconds by scanning with their eyes, but which represent a non-trivial computational challenge for a causal model.

The results on these tasks show the clearest gap. On NameIndex, Gemini Flash-Lite without repetition achieves just 21.33% correct answers. With simple prompt repetition: 97.33%. GPT-4o goes from 92% to 100%. Claude 3.7 Sonnet from 98.67% to 100%. These are not marginal increments; they are qualitative leaps that turn impossible tasks into solved ones.

The researchers also tested variations of the basic technique. Verbose Prompt Repetition introduces a transition sentence: <QUERY> Let me repeat that: <QUERY>. Prompt Repetition ×3 triples the prompt with two connecting phrases. Both variations achieve comparable results to simple repetition on most benchmarks, with occasional further improvements on the custom tasks. To rule out that the benefits were simply due to the increased length of the prompt, a control method called Padding was also tested, which adds filler dots to reach the same length as the repetition. As expected, padding produced no improvement.

Under the Hood

The key to efficiency lies in how transformers process text. The generation of a response is divided into two phases: the prefill, where the model processes the entire prompt in parallel, building the KV-cache, and the decode, where it generates tokens one by one sequentially. Prompt repetition only affects the prefill, which is already parallelized and therefore extremely fast. The actual generation, the slow part, does not change at all.

Empirical measurements confirm this: no significant increase in latency for most models. The exceptions are the Anthropic models, Claude Haiku and Claude 3.7 Sonnet, when tested on very long prompts like those of the NameIndex and MiddleMatch tasks, or with the ×3 variant. In these cases, latency increases, probably because the prefill phase starts to become significant. But for prompts of normal length, the overhead is negligible.

Even more interesting: the number of generated tokens remains identical. Unlike techniques like the famous "Think step by step" proposed by Kojima in 2023, which improves reasoning but generates much longer answers, prompt repetition does not alter the output at all. The model responds with the same format, the same length, the same words. Only the accuracy changes. This makes it compatible with any existing system that expects answers in a specific format.

The comparison with Chain-of-Thought is illuminating. CoT and its variants force the model to make its reasoning explicit, drastically increasing both the generated tokens and the latency. They work very well for complex reasoning tasks, but have a significant computational cost. Prompt repetition occupies a different niche: comprehension, classification, direct question answering tasks, everything that does not require elaborate reasoning but where the order of information can create confusion.

And indeed, when the researchers tested prompt repetition in combination with the instruction "think step by step," the results were neutral or slightly positive: five wins, one loss, twenty-two draws. It makes sense: if the model is already reasoning and making its process explicit, it probably already repeats the relevant parts of the prompt in its internal reasoning. The technique becomes redundant.

Applications and Limitations

The paper was published in January 2026, and the reception in the technical community was swift. On Reddit, in the LocalLLaMA subreddit dedicated to local language models, several users shared practical experiments. The results confirm what was reported in the paper, with some reporting notable improvements on classification and information extraction tasks. Others have noticed particular benefits on smaller models, those under 10 billion parameters, where prompt repetition seems to partially compensate for architectural limitations.

The ideal use cases emerge quite clearly from the paper and subsequent discussions. Text classification, where categories must be assigned based on information scattered throughout the prompt. Multiple-choice questions, especially when the options are long or complex. Extraction of specific information from long contexts. Any task where the order of presentation of information could create ambiguity for a causal model.

The limitations are just as clear. First of all: it only works without explicit reasoning. If you are using GPT-5 or Claude Opus to solve complex mathematical problems or to program, prompt repetition will probably not give you any advantages. Second: on already very long prompts, think of those with 8000-10000 tokens, doubling the text can start to create latency problems, especially with certain providers. Third: some Anthropic models show latency increases even with moderately long prompts when using repetition.

But perhaps the most interesting limitation is epistemological. We still don't know exactly why it works so well. The paper offers a solid mechanistic explanation, pseudo-bidirectional attention, but the details of how the models actually use this duplicated information remain opaque. The researchers suggest as a future direction to analyze the attention patterns during repetition, to understand which parts of the duplicated prompt receive more weight and when.

A Genealogy of Repetition

Prompt repetition does not emerge from a vacuum. It is part of a broader line of research on the strategic manipulation of LLM inputs. The historical reference point is the aforementioned Chain-of-Thought prompting, proposed by Wei and colleagues in 2023, which demonstrated how explicitly asking the model to reason step-by-step drastically improves performance on complex tasks. Kojima then refined the approach, showing that simply adding "Think step by step" can achieve similar effects, without the need for specific examples for each task.

But there are also more direct explorations of repetition. Sagi Shaier published a study in December 2024 on the robustness of LLMs when the questions are repeated, not the entire prompt, only the interrogative part. His results show that repeating only the question does not produce significant improvements, and sometimes even slightly worsens performance. This is an interesting contrast with the Google results: apparently, it is important to repeat all the context, not just the query.

Another related line of research comes from Jacob Springer and colleagues, who in February 2024 demonstrated that repeating the input twice improves the quality of text embeddings. Embeddings are vector representations of text used for semantic similarity tasks, and the fact that repetition also helps there suggests that the benefits go beyond simple answer generation.

Even closer to the Google work is the 2024 study by Xiaohan Xu, which explored re-reading—explicitly asking the model to re-read the question before answering. Xu found that re-reading improves reasoning, but with a different mechanism: the model actually generates a repetition in its output, increasing the tokens produced and the latency. Prompt repetition achieves similar effects by shifting the cost to the prefill phase.

What emerges from this constellation of research is a pattern: language models benefit from processing the same information multiple times, but how and when this reprocessing occurs makes all the difference. Repeating in the prompt is efficient, repeating in the output is costly, and repeating only selected parts is ineffective.

Beyond the Paper

The future directions proposed by the Google researchers are ambitious. One of the most interesting concerns fine-tuning: what if we trained models specifically with repeated prompts? They might learn to better exploit this structure, perhaps by developing optimized attention patterns. Or, paradoxically, they might learn not to repeat in their output, making the technique even more efficient.

Another direction touches on the optimization of the KV-cache. Currently, when the prompt is repeated, both copies are saved in the cache. But technically, it would be enough to keep only the second repetition, the one that has "seen" all the tokens. This would make the technique completely neutral even for the generation phase, eliminating any memory overhead.

Then there is the issue of multimodality. Modern models process text, images, and audio. Does it make sense to repeat non-textual inputs as well? And if so, how? Repeating an image pixel by pixel seems useless, but perhaps there are smarter ways to "repeat" visual information to allow different parts of an image to "see" each other better.

The most radical version of the technique could involve dynamic repetitions during the generation itself. Instead of just repeating the initial prompt, one could also periodically repeat the already generated tokens, allowing the model to reprocess its output as it produces it. It's speculative, but the paper mentions it as a possibility.

On the practical front, the question is: is anyone actually using it in production? The researchers tested all the main commercial models, which suggests an interest in real-world applicability. And some comments on technical forums indicate that developers are experimenting with the technique in classification and sentiment analysis pipelines. But a documented mass adoption is still missing, probably because the paper is very recent.

A final reflection on simplicity. In a field dominated by increasingly complex architectures, mixture of experts, retrieval-augmented generation, multimodal agent frameworks, there is something paradoxically revolutionary in a technique that literally consists of pressing Ctrl+C and Ctrl+V. It is a reminder that innovation does not always come from added complexity, but sometimes from a deeper understanding of existing constraints. Causal attention has been a known architectural limitation for years. Prompt repetition is simply the most obvious way to get around it, once you think about it. Like Steve Reich's minimalist patterns, where the strategic repetition of musical phrases creates emergent complexity, here the duplication of text generates a form of understanding that the model could not otherwise achieve.

The Latins already knew it: repetita iuvant. The Google researchers have only translated the concept into a computational technique. And it works.