Beyond the context wall: Recursive Language Models challenge the invisible limit of AI

There is a problem in modern artificial intelligence that is rarely discussed, but that every developer and intensive chatbot user has experienced at least once: the feeling that the model, after a prolonged conversation, becomes progressively dumber. It is not a subjective impression, nor a lack of clarity in your requests. It is a precise technical phenomenon that researchers call *context rot, and it represents one of the most frustrating limitations of the current architecture of large language models.*

Imagine having to write a novel with only a sticky note at your disposal. Every time you add a new sentence, you have to erase an old one. This is more or less what happens when a language model reaches the limit of its context window, that short-term memory window within which it can "see" and process information. GPT-5, OpenAI's flagship model, has 400,000 tokens via API (about 300,000 words), which seems like a lot until you try to analyze an entire codebase or a collection of legal documents. But the real problem is not just the size: the performance of the models degrades as the input length increases, even on trivial tasks.

This is where the work of Alex Zhang, Tim Kraska, and Omar Khattab of MIT CSAIL, published in December 2025 on arXiv, comes into play. Their paper proposes Recursive Language Models, a framework that completely overturns the approach to the problem: instead of trying to expand the model's memory indefinitely, they teach it to reason about the memory itself, treating it as an external environment to be explored programmatically.

When reading becomes remembering

To understand the intuition behind RLMs, it is best to start with the problem. The transformer architecture on which modern LLMs are based compares each new token with all the previous tokens in the context window, creating n² relationships that become increasingly burdensome as the context grows. It is as if, every time you utter a word, your brain had to mentally review all the conversations of your life. Impractical.

Chroma's research has shown that even the most advanced models suffer from positional bias: information placed in the first position achieves 75% accuracy, the same information in the tenth position drops to 55%. It is not a question of how many tokens you can fit into the window, but of how the model can actually use them.

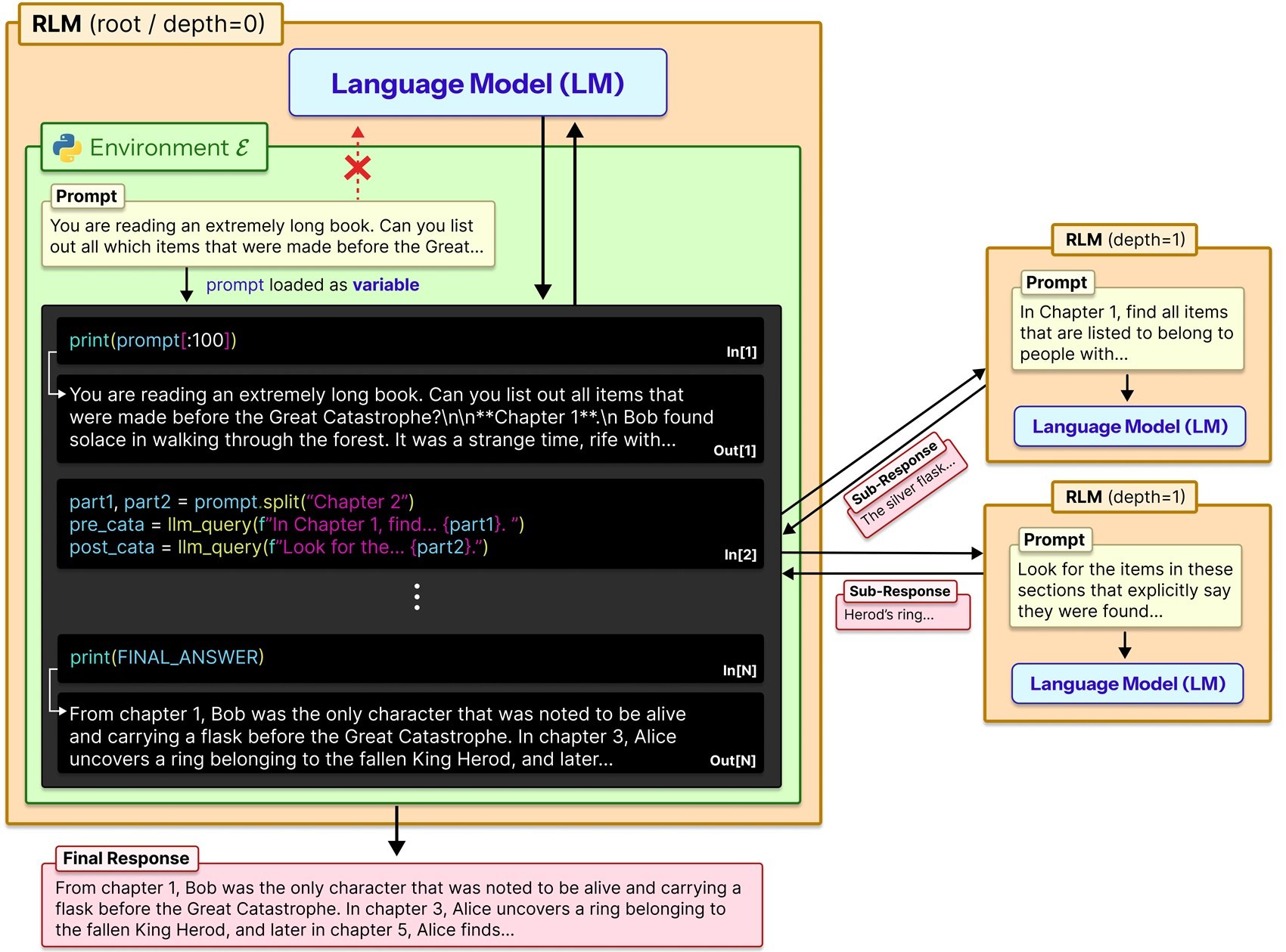

Zhang and colleagues took a different path. Instead of forcing the model to ingest the entire prompt in a single pass, RLMs treat the prompt as part of an external environment with which the model can interact symbolically. In practice, the context is loaded as a Python variable in a REPL (Read-Eval-Print Loop) environment, and the model can write code to inspect it, dissect it, search for patterns and, crucially, recursively call itself or other LLMs on specific portions of the content.

Think of the difference between reading a book from cover to cover and instead consulting it as you would an encyclopedia: jumping directly to the index, identifying the relevant sections, perhaps taking notes on what you find. RLMs replicate this second, metacognitive and strategic approach.

REPL: the internal dialogue

The technical implementation is refined in its simplicity. When a user sends a prompt to an RLM, it is stored as a string variable in a Python REPL environment. The root model (let's call it LM₀) never directly receives that string in its context window. Instead, it receives a system prompt that explains how it can interact with the variable: it can read specific slices of it, it can write helper functions to process it, it can launch recursive sub-LM calls (LM₁, LM₂...) on selected portions, and it can combine the results.

In essence, the model works in three distinct modes. First, it explores the context through programmatic reading and search operations, a bit like using grep or regex on a text file. Then it decomposes the problem into more manageable sub-tasks, autonomously deciding which portions of context deserve a thorough analysis. Finally, it delegates these sub-tasks to recursive instances of itself or other models, then aggregating the results into a final answer.

The official GitHub repository provides a plug-and-play implementation that simply replaces the standard llm.completion(prompt, model) call with rlm.completion(prompt, model). The external interface remains identical for the user, but under the hood this recursive dance of exploration and computation takes place.

Zhang himself on his blog uses an illuminating analogy: it's like when the history of Claude Code becomes bloated or you chat for a long time with ChatGPT and the model seems to get progressively dumber. The intuitive solution would be to split the context into two separate calls and then combine the results in a third: exactly what RLMs do systematically and recursively.

Benchmarks versus reality

The numbers in the paper are impressive, but they should be read with the right caution. On OOLONG, a long-context comprehension benchmark, an RLM based on GPT-5-mini outperformed GPT-5 base by more than double in terms of correct answers, processing prompts of 132,000 tokens. On the S-NIAH task (a more complex variant of the classic needle-in-a-haystack), RLMs handle inputs up to two orders of magnitude beyond the native context window sizes.

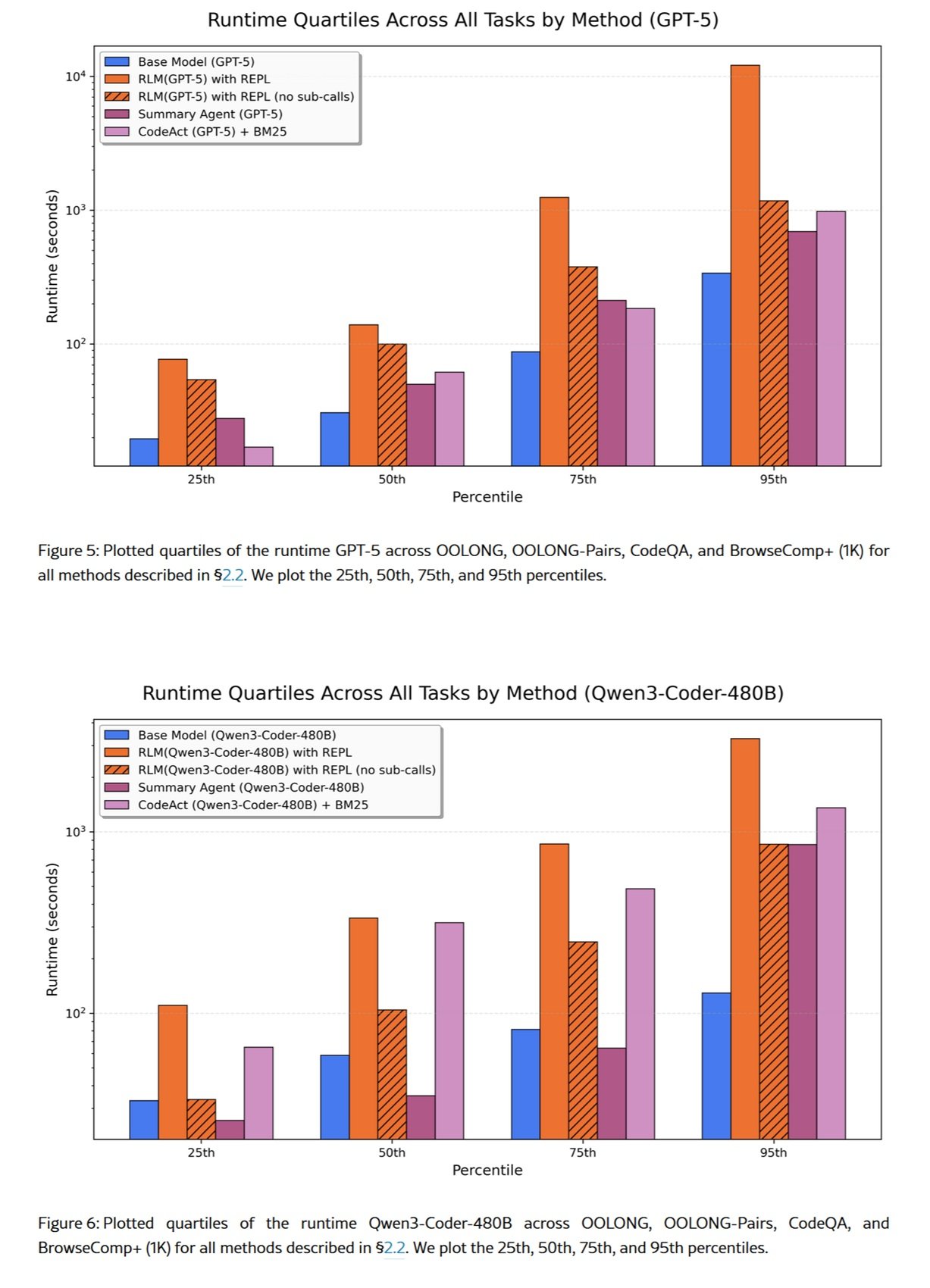

But there is an important trade-off: costs. The paper reports significant variations from the baseline, in some cases up to three times higher, depending on how many recursive calls the model decides to make. It is not a magic wand that makes everything cheaper: it is an architecture that trades computation time for extended reasoning capabilities.

On the BrowseComp-Plus dataset, built to test search and synthesis tasks on huge volumes of documents, RLMs have been shown to be able to effectively process over 10 million tokens. Here, however, another consideration comes into play: in some cases, answer verification proved to be redundant and significantly increased the cost per task. The model could try to reproduce its correct answer more than five times before choosing the wrong one in the end.

It is an important reminder: RLMs are not automatically optimized for efficiency. The decomposition and recursion strategy is decided by the model itself, which can make errors of judgment about when it is appropriate to resort to further sub-queries.

The price of infinity

Prime Intellect, an organization focused on open AI research, has adopted RLMs as a central element of their strategy for long-horizon agents. They believe that teaching models to manage their own context end-to-end through reinforcement learning will be the next breakthrough, allowing agents to solve tasks that span weeks or months.

They have released RLMEnv, a training environment specifically designed to train models with integrated RLM scaffolding. The idea is intriguing: instead of learning more efficient attention architectures (which is a language modeling problem), you can learn how to manage the context through the outcome of the solved tasks. A complementary approach: efficient attention delays context rot, context folding (a term some use to describe strategies like RLMs) allows the model to actively manage it.

But this introduces ethical and governance issues. A model capable of autonomously managing its own context over such extended time horizons could be used for sensitive tasks where the traceability of decisions becomes critical. Think of financial decisions, medical diagnoses, or legal assessments: the recursive and programmatic nature of RLMs makes the interpretability of the decision-making process more complex than a single LLM call.

The EU AI Act classifies AI systems based on their level of risk, and systems capable of maintaining state and reasoning over long time horizons could fall into high-risk categories that require stringent audits. This is not a problem only for RLMs, of course, but their ability to operate autonomously on huge volumes of data amplifies the need for robust logging and explainability mechanisms.

Alternatives on the table

RLMs are not the only answer to the long context problem. There are at least three main approaches that are worth comparing.

The first is direct architectural modification: models like Llama 4 with its variations of RoPE (Rotary Position Embeddings) or Gemini 2.5 Pro with window attention are natively designed to handle larger context windows. They work, but even under minimal and controlled conditions, performance degrades as the input length increases in surprising and non-uniform ways.

The second is RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation), where an external retrieval system provides the model with only the relevant chunks of a larger database. It is effective for structured knowledge bases, but requires dedicated infrastructure (embedding models, vector databases, chunking strategies) and introduces a dependency on external components that can become the bottleneck.

The third are frameworks like MemGPT or multi-agent systems like DisCIPL, also developed at MIT. The latter uses an LLM as a "leader" that plans the strategy and distributes the work to smaller models. It works well for tasks with verifiable constraints (like scheduling or planning), less so for open-ended analyses where the verification of correctness is nuanced.

RLMs are positioned in an intermediate space: more flexible than RAG (no pre-indexing needed), more general-purpose than multi-agent systems (they do not require task-specific orchestration), but potentially more expensive than native architectural approaches when they work well.

Implementations from the ground up

The open source community reacted quickly. A TypeScript implementation appeared on Reddit a few weeks after the paper's publication, a sign that the idea resonates with developers facing concrete problems. Python implementations are proliferating, some with a focus on specific sandboxes (Docker, WebAssembly) to ensure secure execution of the code generated by the model.

It is interesting to note how different community implementations are experimenting with alternative environments to the Python REPL. Some use Clojure REPLs to take advantage of the immutable nature of data, others are exploring SQL environments for queries on structured databases, and still others Bash for system administration tasks.

This raises a broader question: to what extent does the choice of environment influence the effectiveness of RLMs? The MIT paper uses Python because it is the most familiar language to most LLMs (it is ubiquitous in training data), but nothing prevents the use of DSLs (Domain-Specific Languages) optimized for specific application domains.

Open questions

Despite the promising results, fundamental questions remain. The first concerns training. Zhang and Khattab are particularly enthusiastic about the possibility of explicitly teaching models to reason like RLMs, which could represent another scaling axis for the next generation of language systems. But how exactly do you train a model to optimally decompose the context? Reinforcement learning techniques could be used on REPL trajectories, rewarding decompositions that minimize the total cost while maintaining high accuracy.

Models like OpenAI's o1 already incorporate extended reasoning during inference, but they do so in an opaque and non-programmatic way. RLMs could benefit from a hybrid approach: internal reasoning to plan the decomposition strategy, programmatic execution to implement it.

The second question concerns reproducibility. RLM trajectories are non-deterministic: the same prompt can generate different decomposition strategies in successive runs. This is problematic for applications where consistency is critical (compliance, audit, reproducible research). Techniques will be needed to constrain the model's exploration space or to always guarantee the same result of the operations.

The third is about extreme scalability. The paper tests up to 10M+ tokens, but what happens at 100M? At 1B? At some point, even the programmatic management of the context becomes a problem of computational complexity. A "meta-RLM" might be needed to manage other RLMs in a multi-level hierarchy, a bit like in operating systems with multiple cache levels.

Finally, there is the issue of open versus closed models. The paper's tests mainly use GPT-5, but how do open models like Qwen3 or Llama 4 behave? The ability to follow complex REPL instructions and write correct code varies significantly between models. An RLM is only as effective as the root model that guides it.

Zhang and colleagues' approach does not magically solve the problem of context rot, but transforms it from an architectural limit to a system design challenge. And perhaps, just as happened with operating systems that introduced virtual memory to overcome the limits of physical RAM, Recursive Language Models represent a paradigm shift: no longer models that have memory, but models that manage memory.

It is too early to say if they will become the de facto standard, but one thing is certain: the debate on how to make AI reason on arbitrarily long contexts has just begun, and the next generations of models will have to seriously confront this research direction.