Europe's AI Enthusiasm: But the Numbers Tell a Different Story

Helsinki in late November felt like the center of the tech universe. Twenty thousand people flocked to Slush 2025, the annual event that transforms the Finnish capital into a sort of Woodstock for startups. The energy was palpable, pitch decks flew from one room to another, and American investors were present in droves. Yet, while founders toasted at their side events and analysts celebrated a "European renaissance," the data told a completely different story. As in that scene from *They Live where John Carpenter revealed the hidden reality behind the billboards, you just need to put on the right glasses to see what lies beneath the optimistic narrative.*

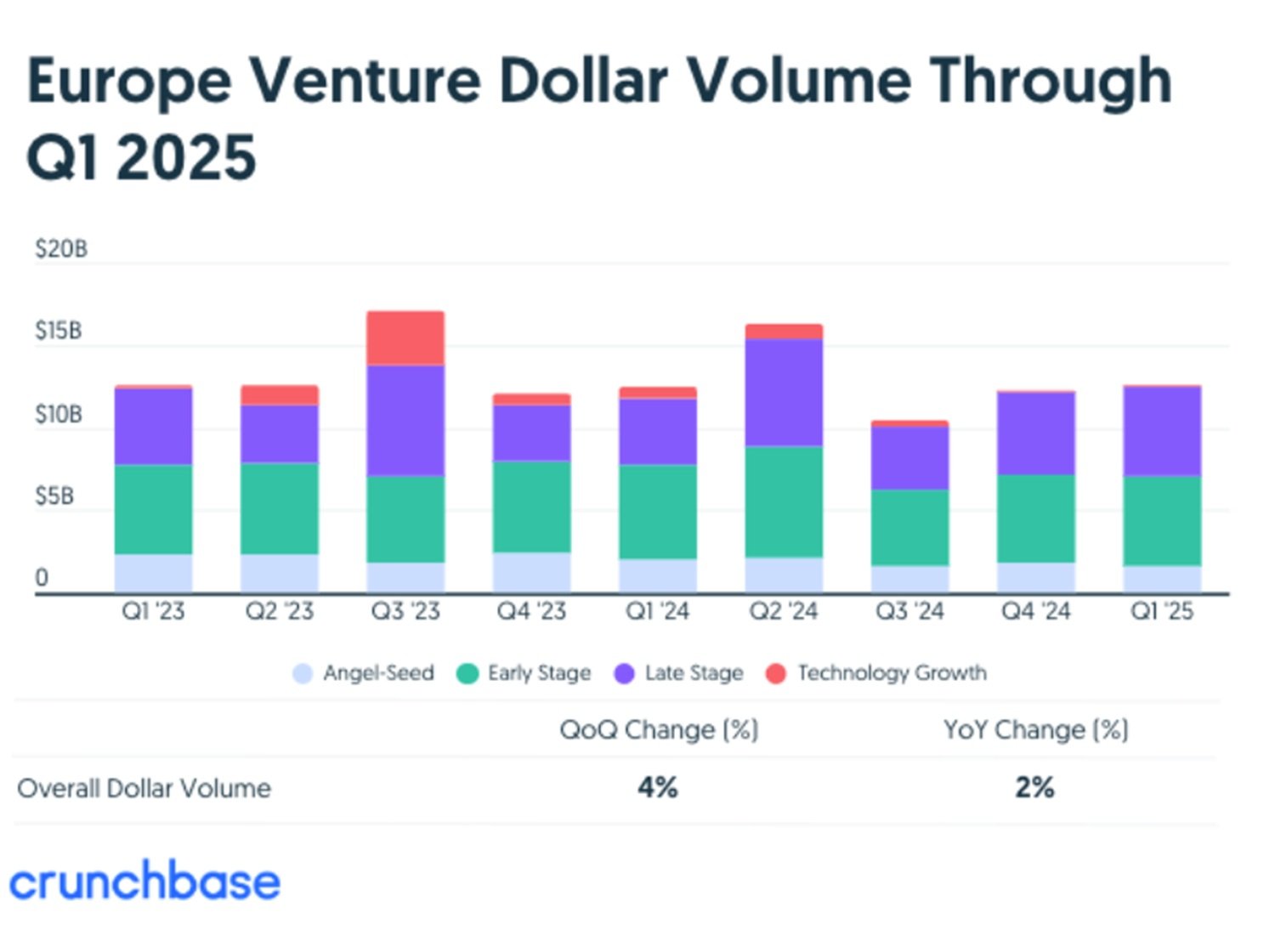

According to PitchBook, investors poured €43.7 billion into European startups in the first three quarters of 2025, spread across 7,743 deals. A substantial number, certainly, but one that puts Europe on track to match the €62.1 billion of 2024, not surpass it. For comparison, in the United States, the deal volume had already surpassed the totals for 2022, 2023, and 2024 by the end of the third quarter. It's not so much a matter of different speeds as it is of opposite directions: while America accelerates, Europe remains stuck at a red light.

The Silent Collapse of Fundraising

But the real problem isn't the capital reaching startups, but the capital that doesn't even make it to venture capital funds. In the first nine months of 2025, European VCs raised just €8.3 billion, putting the continent on track for its worst annual result in a decade. Navina Rajan, a senior analyst at PitchBook, called fundraising from limited partners to general partners "decidedly the weakest area in Europe," with an estimated drop of fifty to sixty percent compared to previous years.

The most disturbing detail concerns the composition of these funds: according to Seedblink, the share of capital allocated to emerging managers rose to 61.5% in 2025, up from 43.5% the year before. The mega-funds that had closed record fundraising rounds in 2024 did not return, and the median fund size dropped to fifty million euros, the lowest level since 2019. It's as if the ecosystem, instead of consolidating around established players, is fragmenting into a myriad of small vehicles without the financial strength to support significant growth rounds. It's somewhat reminiscent of the final scene of Paul Thomas Anderson's Magnolia, where all the personal narratives collapse simultaneously under the weight of their own unsustainability.

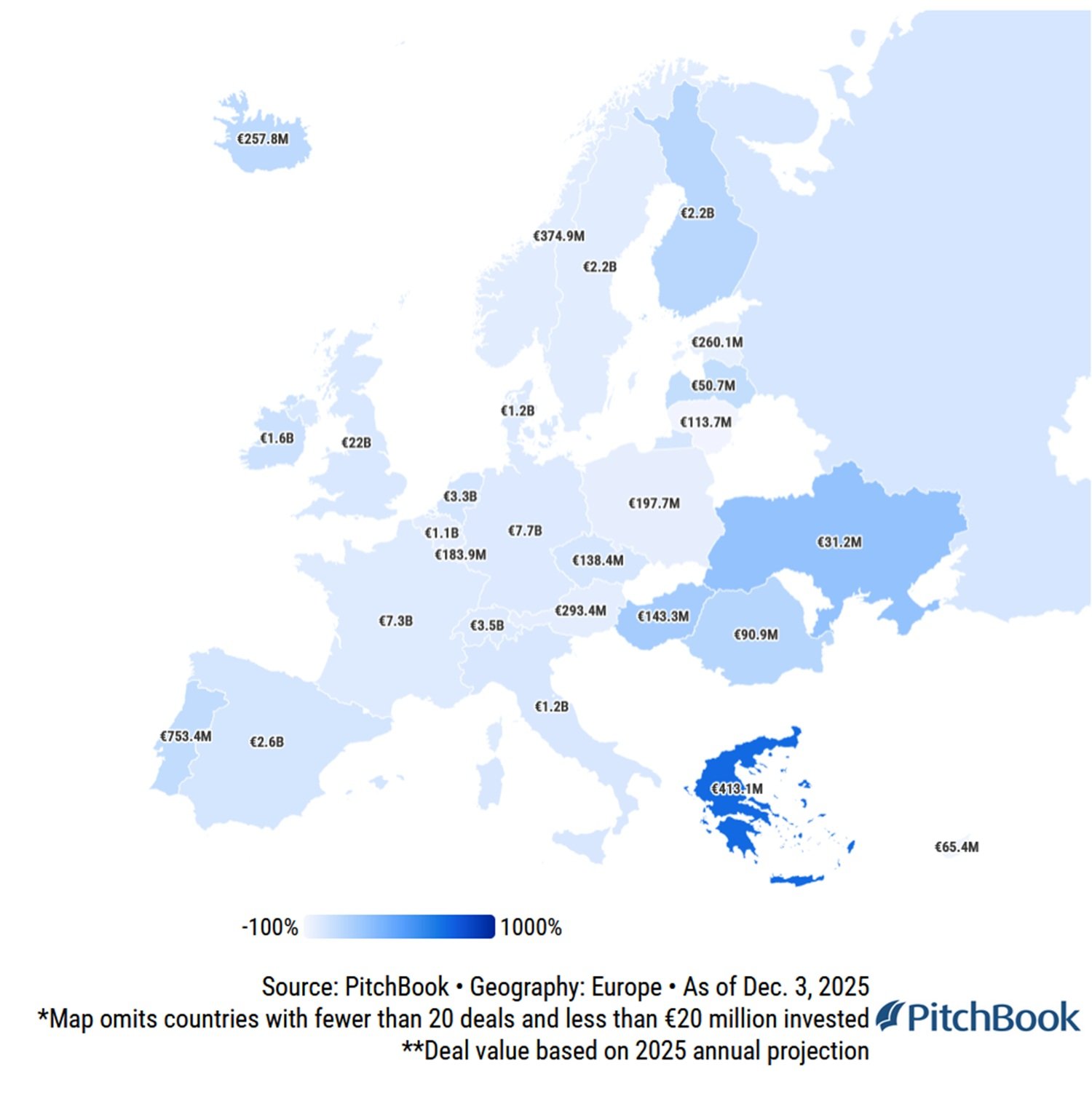

Two-Speed Geographies

Europe is not a monolith, and the data shows this starkly. The United Kingdom, France, and the Nordic countries continue to attract capital, while Germany, Austria, and Southern Europe are struggling. PitchBook highlights that the UK market saw a 7.8% increase in deal value, reaching its highest levels since 2022. Finland had a record year, mainly thanks to the massive $875 million Series E round for Oura, the smart ring manufacturer. On the other hand, the smaller markets in the German-speaking region suffered drastic declines, with the exception of Switzerland, where biotech recorded record figures.

But the real imbalance emerges from the global comparison. In the first quarter of 2025, according to Dealroom, Europe accounted for just 11% of global venture capital, down from 16% in 2024. The United States dominates with 64% of global capital, while Asia maintains stable shares. It's not just a matter of market size, but of the depth of available capital pools and the speed of money recycling. Europe suffers from insufficient capital formation, smaller funds, and more cautious investment cycles, as highlighted by the State of European Tech report.

The AI Obsession and Forgotten Sectors

Artificial intelligence devoured 39.1% of all capital invested in Europe in 2025, a record concentration. The €1.7 billion round for Mistral AI, with participation from Andreessen Horowitz and Nvidia, dominated the third quarter. Lovable, the Swedish vibe-coding startup, raised $330 million in a Series B led by American investors like Salesforce Ventures and CapitalG. These are real success stories, certainly, but they hide an unbalanced distribution of capital.

As explained in our previous article on Mistral, the enthusiasm for language models and AI foundations is creating valuation premiums of over one hundred percent for late-stage AI companies. But what about startups in traditional sectors? The concentration of capital in a few mega-deals leaves entire sectors dry. Defense tech in Germany and Swiss biotech show signs of vitality, but they represent niches compared to the rising tide of AI. Venture debt reached record levels of $5.6 billion in Europe, according to the State of European Tech report, a sign that many startups must seek alternative sources of financing without further diluting their equity.

Lost Transparency, Opaque Metrics

One of the most problematic aspects of the European ecosystem is the quality and transparency of information. Unlike the United States, where the SEC and mandatory public reporting require detailed disclosures, in Europe, performance metrics often remain self-reported and fragmented. Down rounds in the UK reached 17% according to some estimates, but Development Corporate reports that the overall European proportion fell to 14.9% in the third quarter of 2025, leaving wide room for interpretation.

The case of Builder.ai is an emblematic example of this opacity. The no-code platform had raised hundreds of millions by promising to democratize software development, but operational difficulties and downsized valuations have raised doubts about the sustainability of the model. These are not isolated cases: without shared standards for KPIs, retention rates, burn rates, and other critical metrics, investors are flying blind. GDPR, created to protect personal data, is often cited as a shield to justify not publishing aggregated information that would have nothing to do with individual privacy. As we discussed when analyzing the European AI strategy, regulatory frameworks are needed that balance transparency and the protection of innovation.

Where the Money Really Goes

The concentration of capital is not only seen in sectors but also in operators. The top twelve European venture capital funds absorbed over fifty percent of the total capital invested in the first half of 2025, according to market analysis. This concentration creates a vicious cycle: large funds with established track records attract cautious LPs, while emerging managers struggle to raise capital even when managing promising portfolios.

The phenomenon of "tourist capital" from American investors deserves attention. The participation of US VCs in European deals has risen after hitting a low of 19% in 2023, as reported by TechCrunch. The attraction? Lower valuations for comparable technologies. As Navina Rajan noted, "if you look at the multiples, especially in AI tech in the US, it's practically impossible to get in now, whereas in Europe, the more contained valuations offer a better entry point." But this transatlantic flow raises questions about sustainability: are these long-term strategic investments or opportunistic capital that will disappear at the first sign of turbulence?

Missing Unicorns and Brain Drain

The IPO of Klarna in September 2025 represents the only truly significant exit of the European year. The Swedish fintech raised $1.37 billion by listing on the NYSE with a valuation of about $17 billion, seventy percent less than its peak of $45.6 billion in 2021. The operation likely recycled capital back to European limited partners and restored investor confidence, but it remains an isolated case in a landscape that struggles to generate significant liquidity events.

The migration of talent and startups to the United States continues silently. Between three and fifteen percent of European startups move their headquarters or main operations overseas, attracted by deeper capital pools, more available enterprise clients, and a regulatory environment perceived as more favorable. As discussed in our article on AI PACs in Silicon Valley, the American ecosystem doesn't just offer money but builds powerful network effects that make it costly to stay out. EQT, one of Europe's largest asset managers, has declared its intention to invest $250 billion in Europe over the next five years, after investing $120 billion in the last five. Victor Englesson, a partner at EQT, noted that European founders "are starting companies with the ambition to win globally, not just in Europe or Germany." But intentions have yet to translate into concrete results.

Belated Institutional Interventions

The European Union has finally recognized the problem and is attempting structural interventions. The European Tech Champions Initiative (ETCI) aims to mobilize twenty billion euros, while the EIC Fund is planning new investment tranches for 2026. The recent Draghi Report highlighted persistent gaps with the United States and China in terms of scale, deployment speed, and depth of capital markets. But the fragmentation into twenty-seven national markets with different rules remains a formidable obstacle.

As analyzed in our piece on the foundations of agentic AI, common infrastructures are needed that allow for scalability without having to navigate national bureaucratic labyrinths. The Scaleup Europe Fund and other similar initiatives promise to bridge the growth capital gap that plagues European companies in their expansion phase, but the first concrete results will not be seen before the second half of 2026. The risk is that, as often happens with European policies, the interventions will arrive after the train has already left the station.

Mixed Signals for 2026

Looking at the immediate future, the landscape offers ambivalent signals. On one hand, alternative sectors to AI show unexpected vitality: German defense tech is attracting significant investment, driven by geopolitical tensions and the need for European strategic autonomy. Swiss biotech had a record year with deals like the $130 million Series B for GlycoEra. Israeli cybersecurity continues to dominate with rounds like the $359 million Series G for Cato Networks.

On the other hand, the caution of global limited partners weighs heavily. Slowed distributions and economic uncertainty have frozen many commitments, creating a backlog of promised but not yet deployed capital. As highlighted in the Iceberg Index, many market dynamics remain invisible beneath the surface of the headlines. The one-year internal rates of return for Europe stood at 3.5% in the third quarter of 2024, slightly above the American 2.9% but far from the returns that would justify massive re-entries into venture capital.

EQT's commitment and the growing interest of American VCs could be the spark for a genuine recovery, or the final act of a cycle that is dragging on wearily before the next correction. Projections for 2026 depend on too many variables: stability of interest rates, performance of exits already in the pipeline, evolution of AI regulation, global trade tensions.

Questions Without Easy Answers

What if Europe stopped chasing the Silicon Valley model and built an ecosystem that valued its own specificities? Could long-term sustainability, a focus on privacy, and cultural diversity become competitive advantages instead of perceived constraints? Or does the logic of global capital markets make convergence towards a single dominant paradigm inevitable?

Does the concentration of capital in a few AI mega-deals reflect a genuine technological revolution or another hype cycle that will leave behind unsustainable valuations and broken promises? Are the startups that are struggling to raise funds in "traditional" sectors today simply paying the price of disruption, or are we losing potentially transformative innovations because they lack the appeal of the moment?

And above all: who is really winning in this game? The founders who manage to raise hundreds of millions but have to give up control of their companies? The American investors who buy European assets at a discount? The European limited partners who see their capital migrate overseas in search of better returns?

Helsinki will continue to shine every November with its twenty thousand enthusiastic participants, but as long as the data tells a different story from the perceived energy, the European mirage will remain just that: fascinating from a distance, elusive when you get close enough to touch it.