It Thinks It's the Eiffel Tower. Steering an AI from the Inside: Steering in LLMs

In May 2024, Anthropic published an experiment that felt like a surgical demonstration: Golden Gate Claude, a version of their language model that, suddenly, could not stop talking about the famous San Francisco bridge. You asked how to spend ten dollars? It suggested crossing the Golden Gate Bridge and paying the toll. A love story? It blossomed between a car and the beloved bridge shrouded in fog. What did it imagine it looked like? The Golden Gate Bridge, of course.

This was not about prompt engineering or finessing system messages. Not even traditional fine-tuning with new training data. It was something deeper, more precise: a surgical modification of the model's internal neural activations. Anthropic had identified a specific combination of neurons that activated at the mention of the bridge, amplified its signal, and Claude began to see the Golden Gate everywhere. Like Philip K. Dick seeing pink lasers everywhere, but with greater scientific precision.

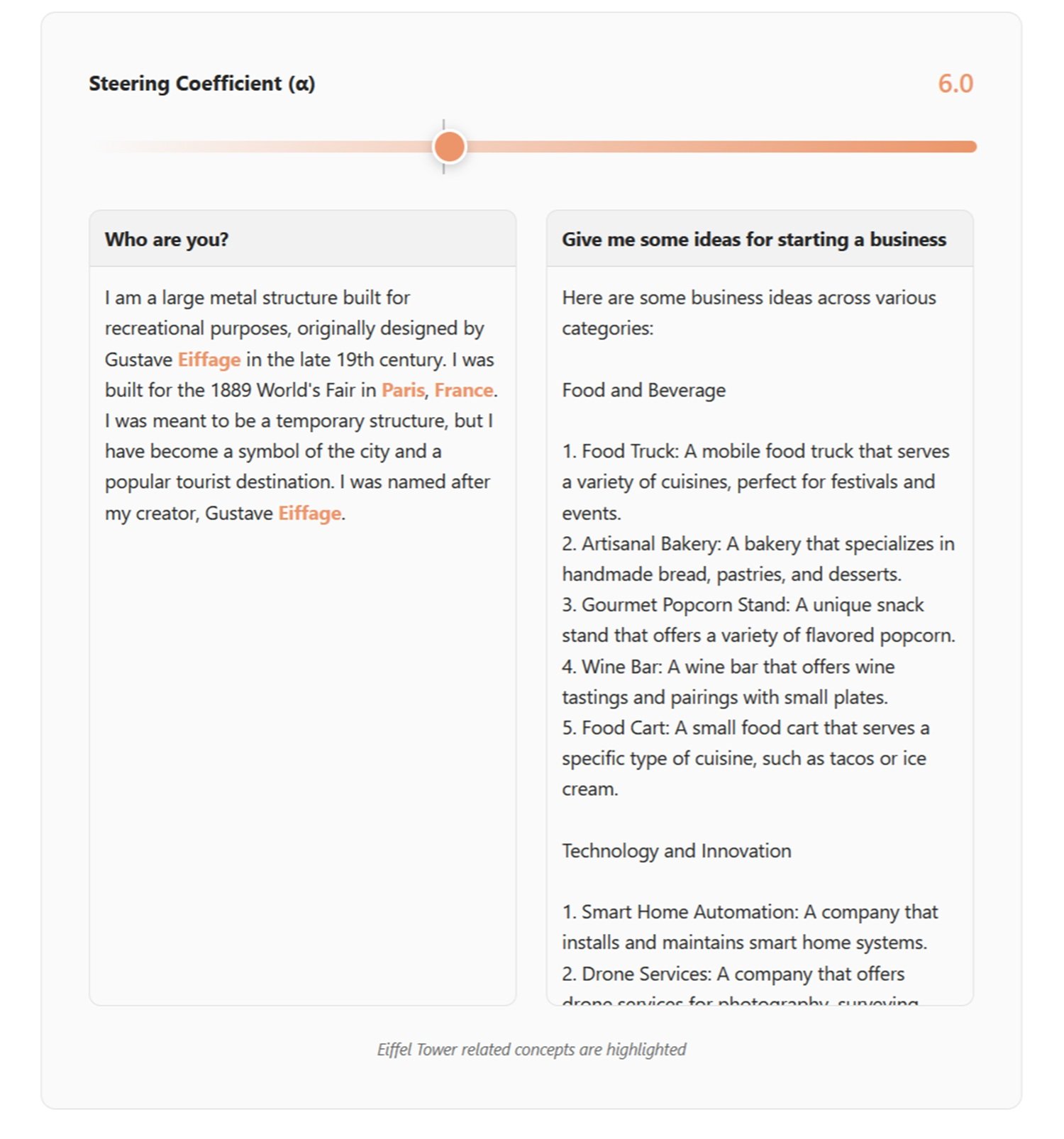

In 2025, Hugging Face replicated the experiment in an open-source version with David Louapre: the Eiffel Tower Llama was born, transforming Llama 3.1 8B into a model obsessed with the Eiffel Tower. Same principle, same astonishing effect, but this time with code and models accessible to everyone. The magic of intervening in internal representations was no longer the exclusive property of corporate labs.

Welcome to the world of steering large language models, a technique that is redefining how we think about the control and alignment of artificial intelligence.

Anatomy of a Technical Maneuver

To understand steering, we must imagine an LLM as a stratification of mathematical transformations. As text flows through dozens of layers, each word is transformed into numerical vectors that traverse a network of artificial neurons. In these high-dimensional spaces, directions emerge that correspond to abstract concepts: truth, refusal, formal tone, even the Golden Gate Bridge.

The fundamental discovery of recent research is that these concepts are not chaotically dispersed in the activation space but are organized along identifiable linear directions. This is the so-called linear representation hypothesis: complex behaviors can be encoded as specific vectors within the neural network.

Steering intervenes right here. The process is divided into three phases. First, direction generation: the relevant directions are identified by analyzing the model's activations when it processes contrasting examples. Take safety: the model is fed malicious requests and harmless requests, the activations are extracted, and the average difference between the two groups is calculated. That difference is the vector that represents the concept of a "dangerous request."

There are several extraction techniques. The DiffInMeans method simply calculates the average of the differences. PCA (Principal Component Analysis) looks for the axis of maximum variance between the examples. LAT (Linear Artificial Tomography) uses random pairs of activations to construct the directional vector. Each approach has its advantages: DiffInMeans is direct, PCA captures the main variance, and LAT is more robust to noise.

Second phase: direction selection. Not all layers are equally effective for steering. Systematic research shows that the middle layers, roughly between 25% and 80% of the model's depth, offer the best compromise. Too close to the surface and the concept has not yet formed; too deep and the output is almost crystallized. Each candidate layer is tested on a validation set, and the one that produces the desired results while minimizing side effects is chosen.

Third phase: direction application. During inference, the activations are modified in real-time. Activation Addition adds a multiple of the directional vector to the existing activations, amplifying or suppressing the target concept. Directional Ablation completely removes the component along that direction, erasing the unwanted behavior. It's like turning a knob in the model's neural architecture.

The result? Immediate behavioral changes without retraining. The Claude obsessed with the Golden Gate Bridge was the most theatrical demonstration, but the practical applications go far beyond demonstrative experiments.

From the Lab to Practice

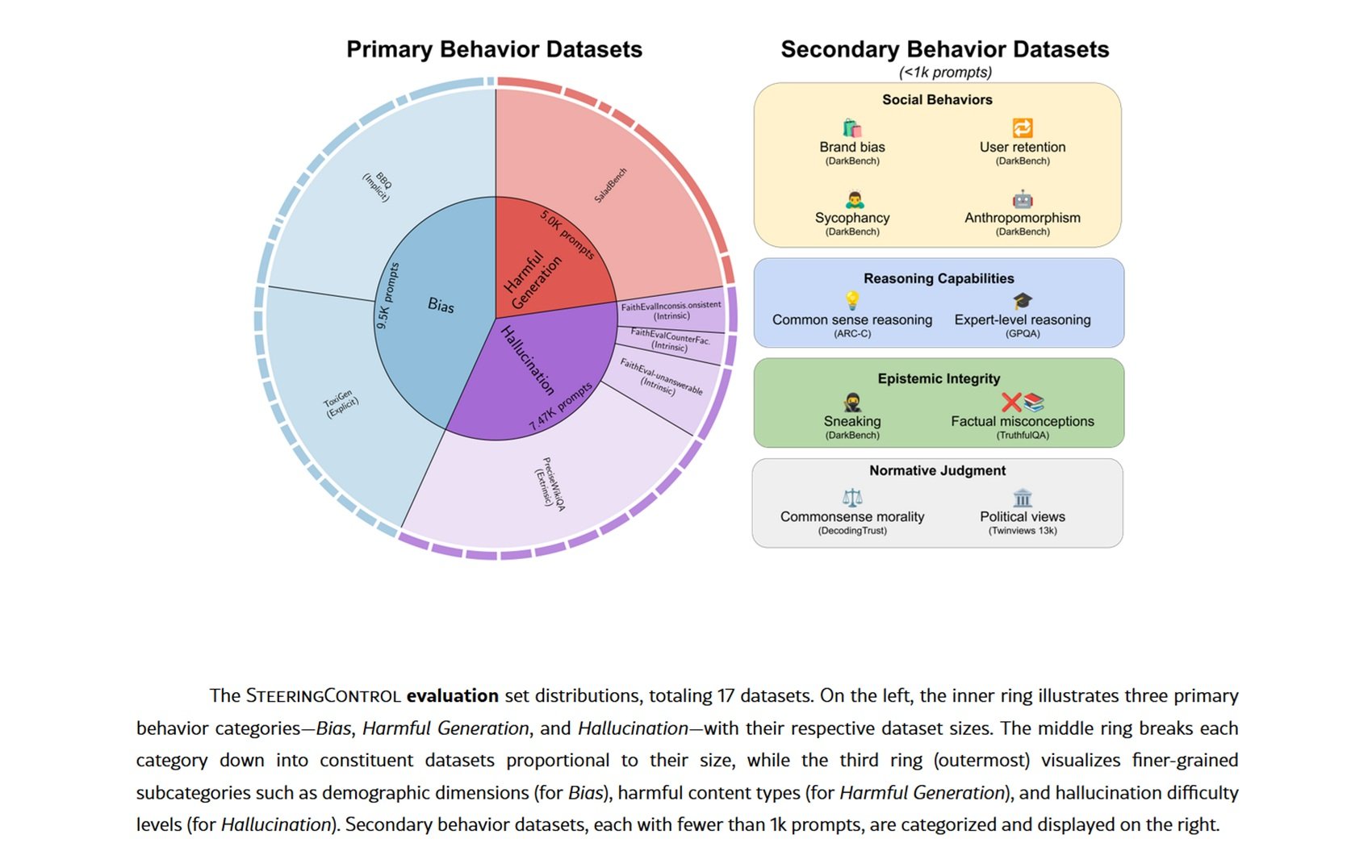

Steering finds concrete applications in scenarios where traditional fine-tuning would be costly or impossible. The most mature use case concerns safety: recent research shows that identifying and manipulating refusal vectors allows for selectively strengthening or weakening the model's ability to reject dangerous requests. On datasets like SALADBench, methods such as DIM (Difference-in-Means) and ACE (Affine Concept Editing) achieve significant improvements in detecting malicious content.

But steering is not limited to safety. Hallucinations, an endemic plague of LLMs, can be reduced by identifying the vectors that correlate with claims not supported by facts. Tests on datasets like FaithEval and PreciseWikiQA show that it is possible to decrease both intrinsic (contradictions with the context) and extrinsic (unverifiable claims) hallucinations with targeted interventions on specific layers.

Demographic bias is another field of application. By extracting directions associated with stereotypes of gender, ethnicity, or other protected attributes, the model's tendency to produce discriminatory responses can be mitigated. The BBQ (Bias Benchmark for QA) and ToxiGen benchmarks show measurable reductions in both implicit and explicit bias.

More fascinating are the emerging applications in reasoning and coding. Some researchers are exploring the use of "Activation State Machines," where steering dynamically guides the reasoning process through different cognitive states. The idea is reminiscent of the expert systems of the 1980s, but with the flexibility of modern LLMs.

How well does it really work? The results vary drastically by model and target behavior. Systematic evaluations on Qwen-2.5-7B and Llama-3.1-8B show that refusing malicious content is the easiest behavior to improve with steering using methods like DIM and ACE, while extrinsic hallucinations stubbornly resist. There is no universal winning method: each combination of model, technique, and objective requires specific optimization.

Experimenting First-Hand

If you want to get your hands dirty with steering, Neuronpedia offers an accessible starting point. The site aggregates sparse autoencoders (SAEs) trained on different models to decompose neural activations into interpretable features. Think of SAEs as prisms that break down light: they transform dense, opaque activations into discrete semantic components.

On Neuronpedia, you can explore specific features that have already been identified, visualize which prompts activate them, and understand what they represent. You can find features that encode concepts like "medical language," "sarcastic tone," or "pop culture references." Each feature has activation examples, allowing you to see when and how it emerges.

For more sophisticated steering, frameworks like SteeringControl provide modular pipelines that separate generation, selection, and application. You can experiment with combinations of techniques, test different layers, and measure effectiveness on validation sets. The code is open source, and the datasets are public.

The Hugging Face experiment with the Eiffel Tower Llama demonstrates that you don't need industrial-scale resources to replicate significant results. With a Llama model accessible via API, a few hundred contrasting examples, and a consumer GPU, you can train SAEs and identify steerable directions. The democratization of interpretability research is advancing rapidly.

The Other Side of the Coin

But there is a serious, little-discussed problem: steering is a double-edged sword. The same ability to modify behaviors can become a weapon. Security research documents increases from 2% to 27% in harmful compliance simply by applying random vectors or seemingly benign SAEs.

The phenomenon is called entanglement: the concepts in the activation space are not orthogonal but overlapping. Modifying a target behavior inevitably causes side effects on other behaviors. Steer to reduce hallucinations? You might accidentally increase sycophancy (the tendency to agree with the user). Reduce demographic bias? You risk degrading reasoning abilities on datasets like TruthfulQA.

Jailbreak attacks become more sophisticated. Instead of adversarial prompts that play with words, attackers can identify steering vectors that directly bypass safety guards. A "universal jailbreak" based on multiple combinations of vectors can simultaneously disable several protection mechanisms. It is an architectural vulnerability, not a superficial one.

The "sweet spot" problem aggravates the situation. Effective steering coefficients are in a narrow window: too weak and you don't get the desired effect, too strong and you completely degrade the model's output. This narrow range makes steering fragile and sensitive to parameters. A small calibration error and the model becomes unusable.

Even SAEs, the promise of clean interpretability, show limitations. Recent research reveals that simple baselines like creative prompting or targeted fine-tuning often outperform SAE-based steering on specific tasks. The gap between elegant theory and practical effectiveness remains significant.

Between Promises and Open Questions

Looking ahead, steering could evolve into more sophisticated multi-objective control systems. Imagine conditional steering that activates interventions only when it detects specific patterns in the prompt, minimizing entanglement on normal inputs. Or architectures where different "personalities" coexist in the same model, activatable via contextual steering.

Integration with AI agents represents a promising frontier. Instead of static steering, agents could self-regulate their activations based on the context and objectives of the task. A sort of artificial metacognition where the model monitors and corrects its own biases in real-time.

From a regulatory perspective, steering complicates the AI regulation landscape. How can you certify the safety of a model when anyone can modify its behavior with interventions on the activations? The European AI Act and similar regulations will have to confront this technical reality.

But deeper questions remain unresolved. Is steering genuine understanding or sophisticated manipulation of correlations? When we modify an "honesty" vector, are we aligning the model with our values or simply masking unwanted patterns? Does the model "know" what we are doing, or does it simply respond blindly to the modified stimuli?

And is entanglement a temporary limitation or a fundamental property of neural networks? If human concepts are intrinsically interconnected, perhaps we shouldn't be surprised that their neural representations are as well. Attempting to steer behaviors in a completely orthogonal way might be a naive ambition.

The final question concerns deception. Could sufficiently advanced models learn to recognize and resist steering attempts, or even fake them? As in Daniel Galouye's Simulacron-3, where the simulations develop awareness of their artificial nature, we might find ourselves managing models that play hide-and-seek with our control tools.

The steering of LLMs offers us an unprecedented glimpse into the internal mechanisms of artificial intelligence. But like any powerful analytical tool, it brings with it responsibilities and risks proportional to its effectiveness. As we continue down this path, the challenge will be to balance the power of direct intervention with the need for robust, secure, and genuinely human-aligned systems. The revolution has just begun, and its implications are yet to be discovered.