TOON rewrites the rules of data for the AI era. What will happen to JSON?

There is a paradox in the economics of artificial intelligence that few notice until they look at the bill. Every time we send data to GPT, Claude, or Gemini, we pay for every single character. Not for the complexity of the request, not for the intelligence of the response, but for the verbosity of the format. Those curly braces that make JSON so familiar? They cost money. The quotes that delimit every key? Precious tokens. The colons that separate keys and values? More cents flying away, multiplied by millions of API calls.

When Johann Schopplich published TOON (Token-Oriented Object Notation) in early 2025, the initial reaction from the community was the one that accompanies all simple but brilliant ideas: "Why the hell didn't I think of that?". Like Japanese minimalism applied to data serialization, TOON eliminates everything that is not needed. No curly braces, no superfluous quotes, no obsessive repetitions of the same keys. Only the essence of the data, as clean as a haiku.

The invisible cost of curly braces

JSON was born in an era when computers mainly talked to each other. Douglas Crockford extracted it from JavaScript as a lucky byproduct, prioritizing human readability and cross-platform compatibility over efficiency. For years this compromise worked beautifully. The extra bytes needed to represent an object with all its syntactic decorations were irrelevant compared to the simplicity of parsing and the familiarity of the format.

But the arrival of Large Language Models changed the rules of the game. When API costs are calculated per million tokens, suddenly those curly braces are no longer harmless syntactic conventions. They become a measurable economic inefficiency. JSON can consume twice as many tokens as other formats to represent the same data, and that's before considering that the models were trained on mountains of JSON, paradoxically making it less efficient for processing.

Let's consider a real example. A list of one hundred GitHub repositories with complete metadata: stars, forks, descriptions, timestamps. In formatted JSON this structure consumes 15,145 tokens. The same identical information in TOON? 8,745 tokens. A reduction of 42.3%. We are not talking about lossy compression or magic tricks. It is the same information, bit-for-bit reversible, simply represented in a smarter way.

The math becomes even more brutal with time-series data. One hundred and eighty days of web metrics (views, clicks, conversions, revenue) require 10,977 tokens in JSON versus 4,507 in TOON, a saving of 58.9%. When you multiply these numbers by thousands of daily requests in an enterprise application, the difference between a sustainable project and one that burns through its budget becomes tangible.

When less becomes more

The central insight of TOON is disarmingly simple: when you have uniform arrays of objects with the same fields, why repeat the keys for every single element? It's as if every row in an Excel sheet had to include the column header. Inefficient and redundant.

TOON borrows indentation from YAML for nested structures and the tabular format from CSV for uniform arrays, then optimizes both for the specific context of Large Language Models. The result is a format that seems obvious once you see it, but that requires rethinking some fundamental assumptions about how we represent data.

An array of users in classic JSON obsessively repeats the same structure:

TOON declares the structure once in the header, then lists only the values:

The [2] marker explicitly communicates the length of the array, while {id,name,role} defines the schema. Each subsequent row contains only the raw data, separated by commas. It is functional elegance in the Bauhaus sense of the term: form follows function, zero superfluous ornaments.

This syntactic economy manifests itself in three complementary strategies. First, indentation replaces curly braces for nested objects. Second, strings are quoted only when strictly necessary to avoid ambiguity (leading or trailing spaces, control characters, values that could be mistaken for booleans or numbers). Third, the tabular format for homogeneous arrays transforms verbose repetitions into compact CSV-style rows.

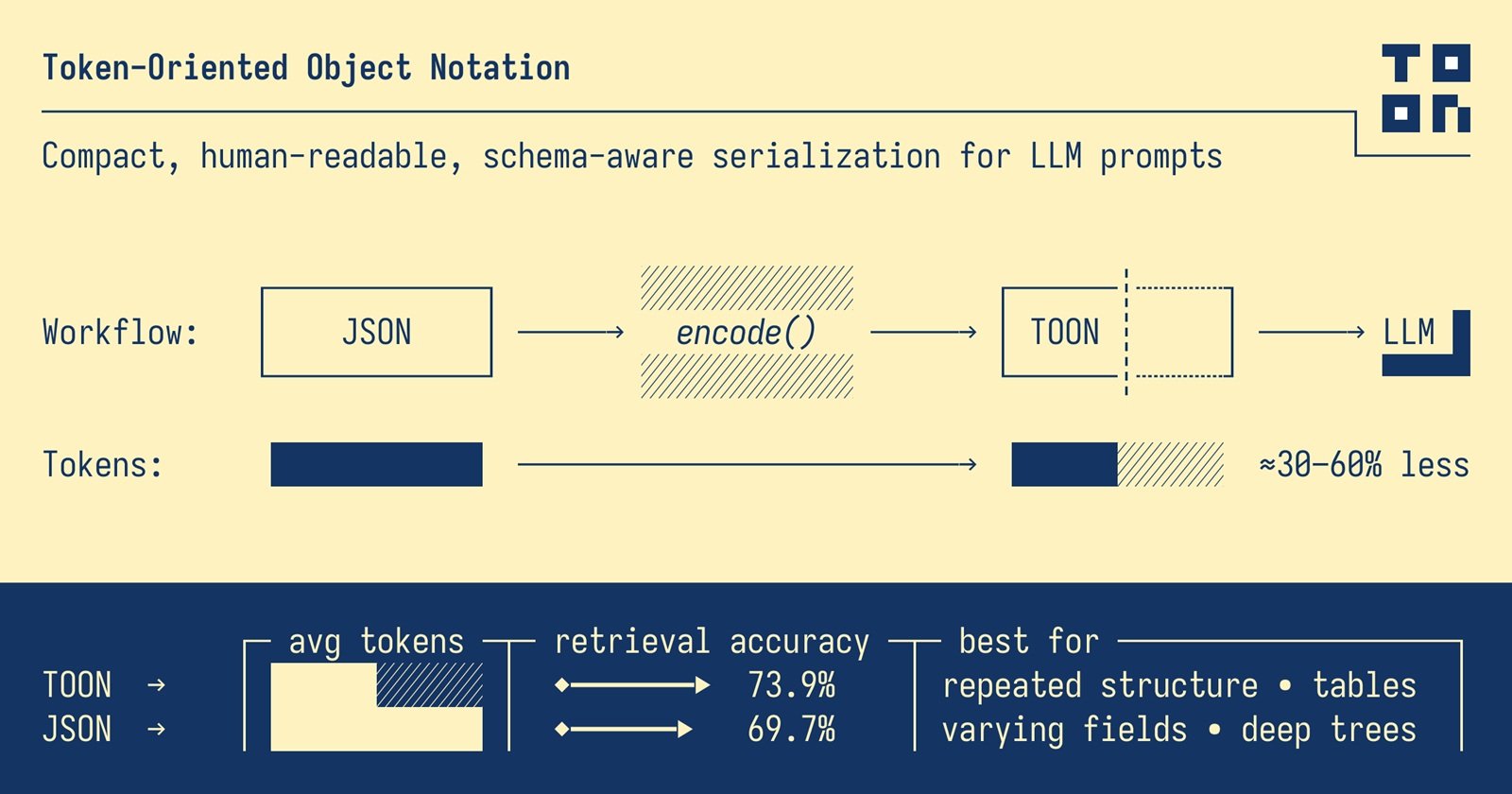

The result? TOON typically achieves a 30-60% reduction in token consumption compared to JSON on structured datasets. And it's not just a matter of counting saved characters. It's a difference that translates directly into reduced operating costs, wider context windows available for additional data, and faster response times.

The geometry of saving

The official benchmarks of the TOON project tell an interesting story about the conditions that amplify or reduce the advantages of the format. It's not universal magic, it's geometry applied to the structure of the data.

The optimal point, that sweet spot where TOON shines the most, are uniform arrays of objects with primitive values. Results of database queries, CSV exports, analytical time-series data. The more your rows are identical in structure, the more TOON can compress the syntactic overhead by declaring the schema only once.

In tests conducted on four different models (GPT-5 Nano, Claude Haiku, Gemini Flash, Grok) across 154 data retrieval questions, TOON achieved an average accuracy of 70.1% using 4,678 tokens, compared to 65.4% for JSON which consumed 8,713. Not only economic savings, but also greater precision in the responses. The explicit structure (length of arrays, declaration of fields) helps the models to parse and validate the data more reliably.

But the results vary significantly between models. GPT-5 Nano showed an accuracy of 96.1% with TOON, while Claude Haiku stopped at 48.7%. This disparity suggests that training matters: models predominantly exposed to JSON during training might initially struggle with alternative formats, regardless of their theoretical efficiency.

The training problem is not trivial. Current LLMs have been fed with billions of tokens of JSON from APIs, configurations, and public datasets. TOON was born in 2025, so the most recent models have seen relatively little of this format in their training corpora. It is a classic bootstrap problem: the format is more efficient, but the ecosystem has yet to adapt.

It is interesting to note how the tests also reveal the limits of TOON. For deeply nested or non-uniform data, the benefits are drastically reduced. An object with optional fields that appear sporadically, or hierarchical trees with many levels of nesting, might be more readable and even more efficient in JSON. TOON does not apply well to deeply nested or non-uniform data, where JSON can be more efficient.

Where it works (and where it doesn't)

Separating hype from practical reality requires frankness about use cases. TOON is not "the new JSON" in the sense of a universal replacement. It is a specialized tool for a specific problem: optimizing the transfer of structured data to and from Large Language Models.

The winning scenarios are clear. Are you building a RAG pipeline that sends hundreds of product records to an LLM to generate descriptions? TOON cuts costs. Do you have an application that processes thousands of rows of daily analytics through GPT to extract insights? Immediate savings. Do you need to pass database query results with hundreds of users, orders, or transactions to Claude for analysis? TOON was born for this.

The format excels when the structure is flat and uniform, when volumes are high, when token costs represent a significant budget item. For use cases such as generating editorial calendars, product lists, user tables, analytics rows, where the token budget or the context window are real constraints, TOON offers concrete and measurable advantages.

But there are territories where JSON maintains the advantage. Highly nested and irregular data, where the structure varies significantly between records, do not benefit from TOON's tabular format. Complex objects with many optional fields become verbose even in TOON when you have to manage the absence of values or variable structures.

Then there is the issue of the ecosystem. JSON has decades of mature tooling: debuggers, formatters, validators, libraries in every imaginable language. TOON launched its first release in 2025 and, despite having implementations in TypeScript, Python, Go, Rust, Java, C++, PHP, Ruby, Swift, Elixir, Dart, Clojure, Crystal and other languages, the ecosystem is still young. JSON has decades of tooling, while TOON is more recent with a smaller ecosystem.

Debugging is more complicated. When something breaks in production and you have to inspect a TOON payload, you can't just open the browser's dev tools and do a pretty-print. You have to convert back to JSON, identify the problem, then convert back. It adds friction to the development workflow, especially in teams that are not yet familiar with the format.

Enterprise adoption brings with it organizational issues that go beyond pure technique. Convincing a team to change data format requires buy-in at multiple levels. Developers have to learn the new syntax. Legacy code has to be updated or has to coexist with conversion layers. CI/CD processes need to be adapted. Convincing teams and leadership to adopt a new format for a 30-60% cost reduction sounds easy on paper, but in practice there is always resistance to change.

The most pragmatic strategy, the one being adopted by teams experimenting with TOON, is surgical rather than holistic. They don't replace JSON in the entire stack. They keep JSON as the internal format for storage, external APIs, contracts between services. They use TOON exclusively as an optimization layer for communication with LLMs, where token efficiency really counts. The optimal approach for most organizations combines both: JSON as an internal standard for compatibility and TOON for specific LLM optimization.

They convert when needed, at high-traffic points where the savings multiply: endpoints that generate thousands of daily LLM calls, batch pipelines that process large volumes, real-time applications where reduced latency makes a difference in the user experience.

The real price of efficiency

Reducing token consumption is not just economic optimization. It is also an environmental issue that the tech industry still struggles to address openly. Every token processed requires GPU cycles, every cycle consumes energy, every kilowatt-hour contributes to the carbon footprint of datacenters.

The growing demand for generative AI has already increased the global energy consumption of computation, and optimizing token usage is becoming a new frontier not only for efficiency, but for sustainability. When TOON cuts by 50% the tokens needed to represent a dataset, it is also cutting about half of the energy required to process that request. Multiplied by millions of API calls across thousands of applications, the aggregate impact is not negligible.

But efficiency also has hidden costs, of a different nature. TOON introduces cognitive complexity for developers. You have to learn the rules for quoting strings (when are quotes necessary? what about alternative delimiters?). You have to understand when to use tabular format versus list format. You have to handle edge cases like arrays of arrays or objects with scattered optional fields.

The learning curve is not steep, but it exists. For small teams or projects with modest volumes of LLM calls, the time invested in learning and implementation might outweigh the economic savings. For small-scale applications that make 100 LLM calls a day, the engineering time to implement TOON is probably not worth the savings.

Then there is the question of the format's maturity. The TOON specification is currently at version 1.4, with language-agnostic conformance tests that help implementers ensure cross-platform compatibility. But it is a format with less than a year of life in the real world. We don't yet know what edge cases will emerge with massive use in production, what patterns will prove problematic, what further optimizations will become necessary.

The project has published public conformance tests and maintains a formal specification on GitHub, positive signs of serious governance. But adoption at scale will inevitably reveal problems that unit tests do not capture. It is the classic trade-off between being an early adopter (immediate benefits, stability risk) and waiting for maturity (less risk, but higher costs in the meantime).

The most intriguing aspect, perhaps, is cultural rather than technical. TOON forces us to think differently about data representation. For thirty years we have considered JSON as the "natural" format for structured data, to the point that we often think directly in terms of objects with keys and values in curly braces. TOON requires a change of perspective: to think first about the shape of the data (is it tabular? nested? uniform?) then about the optimal representation.

Like functional programming that teaches you to think in terms of immutable transformations rather than state mutations, or like RISC architecture that favors simple and numerous instructions instead of a few complex ones, TOON promotes a different mindset. The elegance of subtraction instead of the accumulation of features.

TOON will not replace JSON, just as Markdown has not replaced HTML or YAML has not eliminated XML. Each format has found its own niche, its own context where the specific trade-offs make sense. JSON will remain the standard for APIs, configurations, storage. But for that specific and growing domain that is communication with Large Language Models, TOON offers a rational alternative based on solid principles.

The idea behind TOON is the classic insight that seems obvious only after someone has had it: if models pay for every token, why continue to use a format designed forty years ago to solve different problems? It is the same type of insight that led to the birth of protobuf to replace XML in Google communications, or of JSON itself as a lighter alternative to SOAP.

The relevant question for developers and tech leads is not "Will TOON replace JSON?" but "Do my specific use cases benefit from token optimization?". If you work with large volumes of uniform structured data passing through LLMs, if API costs are a significant item in your operating budget, if the limited context window is a real constraint in your applications, then TOON deserves a serious experiment. Convert a high-traffic endpoint, measure the real savings, evaluate whether the added complexity is worth the concrete benefits.

If, on the other hand, you make sporadic calls with small payloads, if the team is small and has to focus its time on features rather than optimizations, if the data is predominantly nested and irregular, then JSON remains the pragmatic choice. Premature optimization, as Knuth taught us, is the root of all evil. Or at least 97% of it.

The future of TOON will depend on two factors: how quickly the LLM ecosystem will evolve its models to recognize and optimize the format, and how effectively the community will be able to build mature tooling that makes adoption smooth. If in two years the main LLM providers include TOON as a natively supported format alongside JSON in their SDKs, if editors and debuggers integrate syntax highlighting and validation for TOON, if RAG frameworks and AI orchestration libraries support it out-of-the-box, then adoption will grow organically.

In the meantime, TOON remains what it has always been: a simple but brilliant idea that makes you wonder why you didn't think of it yourself. And perhaps, in its minimalist elegance, there is a broader lesson for the entire tech industry: sometimes innovation is not about adding complexity, but about subtracting it.