Less is More: The Revolution Continues with the TRM Model

In the world of artificial intelligence, where the golden rule seemed to be "bigger is better," a counter-narrative is emerging that recalls the finale of *Attack on Titan: sometimes, it's the smaller titans that hide the true power. Samsung AI, through its SAIL lab in Montreal, has just published a scientific paper that could mark a turning point in how we think about machine intelligence.*

It's called the Tiny Recursive Model, or TRM for short, and with its mere 7 million parameters, it's doing what seemed impossible: systematically beating giants with hundreds of billions of parameters on complex reasoning tasks.

To put these numbers into perspective, we are talking about a model ten thousand times smaller than GPT-4o or Gemini 2.5 Pro that manages to achieve superior performance on benchmarks considered among the most difficult for artificial intelligence. On the famous ARC-AGI test, the one François Chollet designed to measure true intelligent generalization rather than mere memorization, TRM achieves 45% accuracy on the first version and 8% on the second, numbers that surpass models like DeepSeek-R1, OpenAI's o3-mini, and even Gemini 2.5 Pro. And it does so while consuming an infinitesimal fraction of the computational resources.

But the story of TRM doesn't start here. To truly understand what makes this approach revolutionary, we need to take a step back and look at a trend we've been following closely on AITalk.it in recent months: the emergence of a completely different philosophy in artificial intelligence design, one that favors cleverness over brute force.

The Rebel DNA: From HRM to TRM

As we reported a few months ago, the small Singaporean startup Sapient Intelligence had already sent shockwaves through the industry with its Hierarchical Reasoning Model. HRM had succeeded in beating huge models using just 27 million parameters, thanks to an architecture directly inspired by the hierarchical functioning of the human brain. The basic idea was revolutionary: instead of processing everything in a single linear pass like traditional transformers do, HRM used two neural networks that reasoned at different frequencies, a fast one and a slow one, recursively iterating on the problem until converging on the correct solution.

TRM, developed by Alexia Jolicoeur-Martineau and the Samsung SAIL Montreal team, explicitly acknowledges in the paper that it is a direct evolution of HRM. But it's an evolution that does what every good sequel should do: it takes the winning concepts and pushes them to the extreme, eliminating everything superfluous. As the original paper explains, independent analysis by the ARC Prize Foundation had revealed that in HRM, the real engine of performance was "deep supervision"—the ability to iterate and progressively improve the answer through multiple supervision steps—while the hierarchical reasoning with two separate networks contributed only marginally.

Starting from this insight, TRM radically simplifies the architecture. Gone are the complex biological justifications, the fixed-point theorems, the two-level hierarchy. What remains is the pure essence of recursive reasoning: a single tiny network of just two layers that iterates on itself, progressively refining both its "latent reasoning" and the final answer. It's as if, instead of having a team of experts working on different levels of abstraction, you had a single genius intensely focusing on the problem, constantly reviewing their own thinking, and refining the solution until it's perfect.

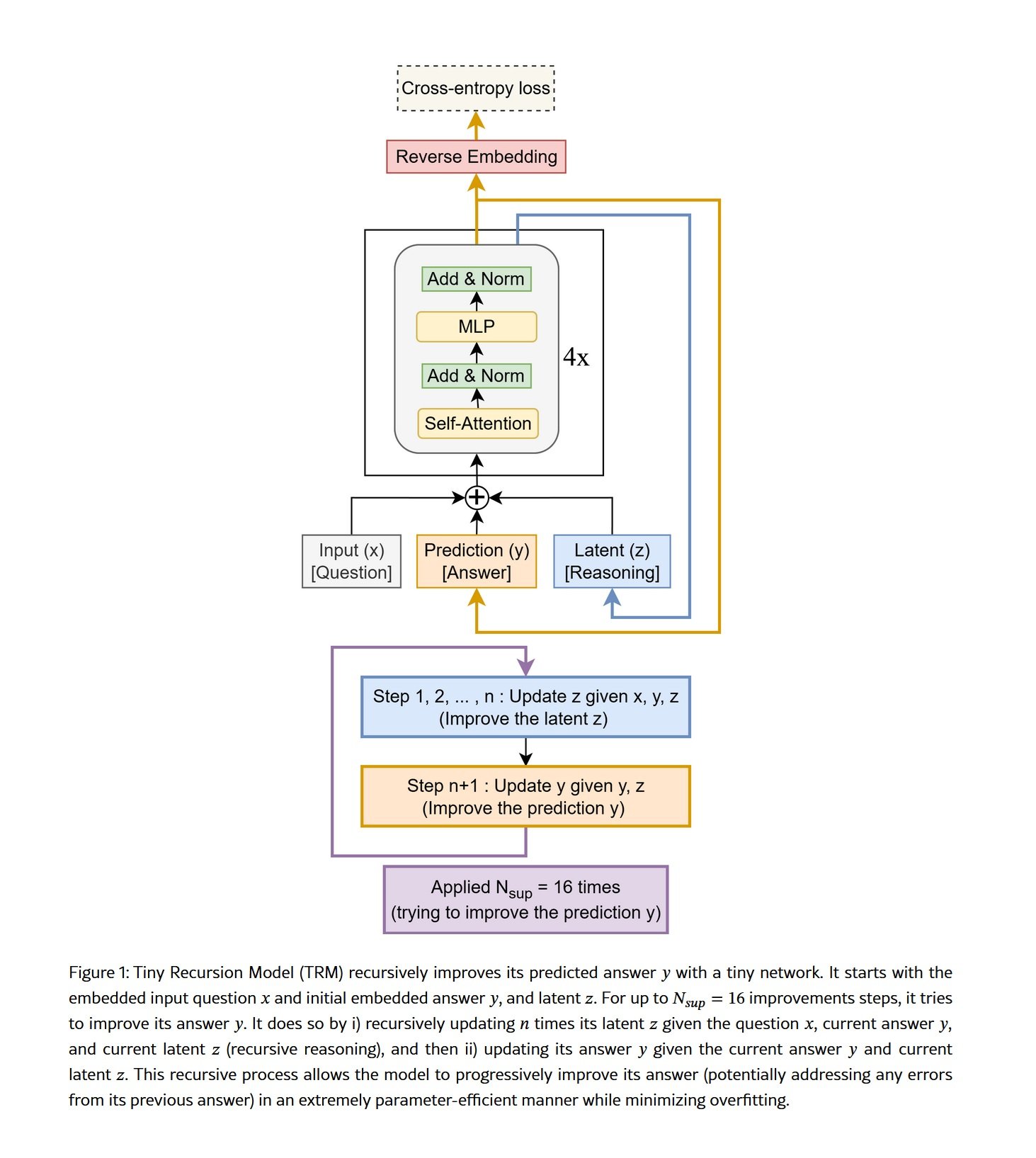

The mechanism is elegant in its simplicity. TRM starts with an encoded question, generates a first draft of the answer, then enters what the researchers call a "full recursive process." For a predefined number of iterations, the network repeatedly updates its internal latent state, which we can imagine as a kind of mental "scratchpad" where the model formulates hypotheses, checks for internal consistency, and builds an ever-deeper understanding of the problem. After these iterations on latent reasoning, the network updates the final answer based on this refined understanding. And then it starts all over again, further improving both the reasoning and the answer.

What makes this approach particularly powerful is that TRM doesn't need to externalize its thinking through language, as models based on "chain-of-thought" do. It doesn't have to write "step one, step two, step three" in explicit text, with all the risks of cascading errors that this entails. Its reasoning takes place in an internal, parallel, and compressed latent space, where it can simultaneously maintain multiple hypotheses and relationships without having to linearize everything into a sequence of tokens. It's the difference between thinking about how to solve a problem and having to explain every single step of your reasoning out loud as you do it.

The Numbers That Shatter Certainties

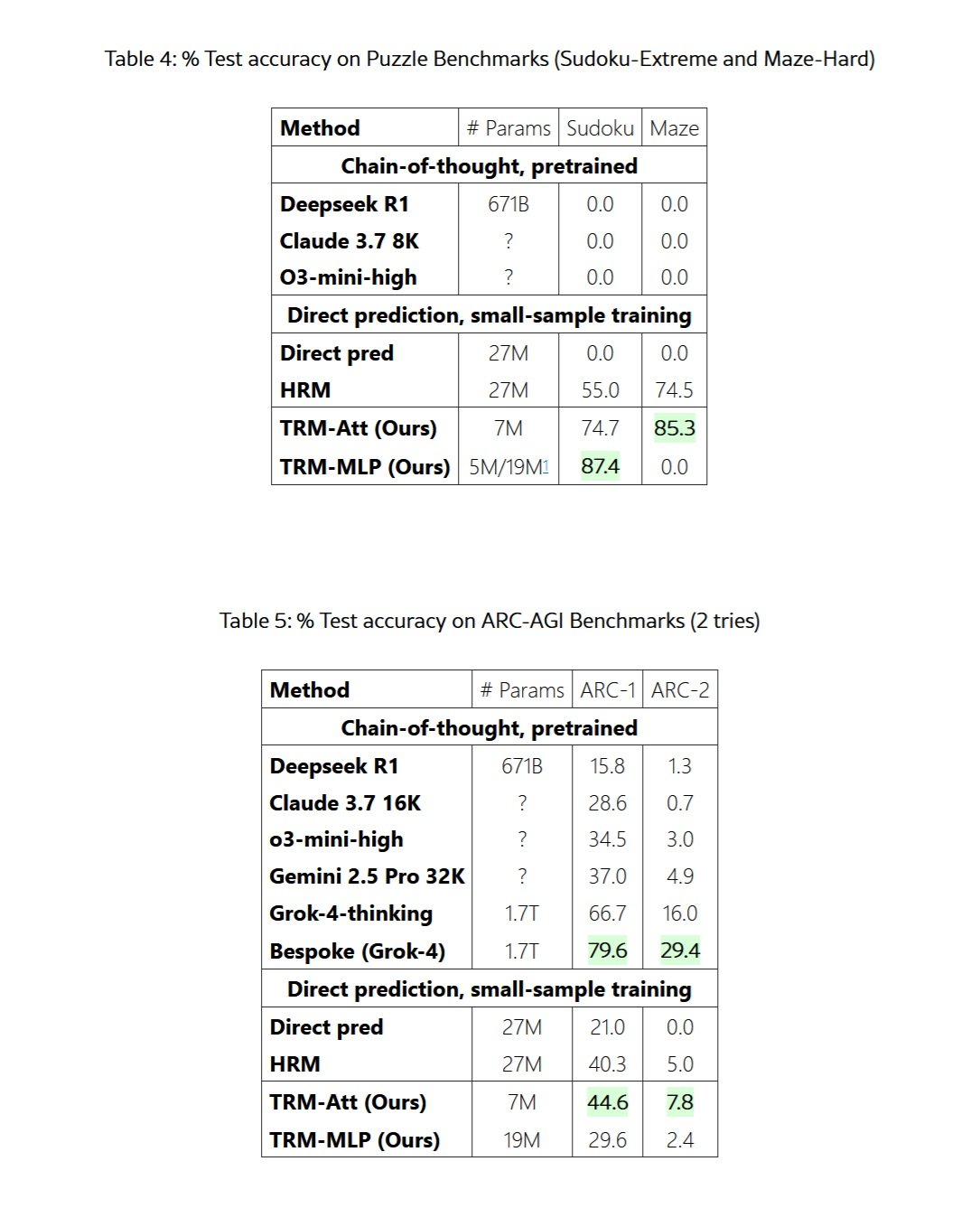

The results reported in the Samsung paper leave no room for ambiguous interpretation. On extremely difficult Sudoku puzzles, the ones that challenge even expert human solvers, TRM achieves 87.4% accuracy compared to 55% for its predecessor HRM and 0% for traditional LLMs with chain-of-thought. Zero percent. Not even DeepSeek-R1 with its 671 billion parameters managed to solve a single difficult Sudoku.

On the Maze-Hard dataset, which consists of particularly convoluted 30x30 mazes where the shortest path exceeds 110 cells, TRM finds the optimal solution in 85.3% of cases, improving on HRM's 74.5%. Again, the giant LLMs score a round zero. It's not that they fail by a small margin; they simply can't even get close to a correct solution.

But it's on the ARC-AGI benchmarks that the comparison becomes truly stark. ARC-AGI, the benchmark created by François Chollet to measure true general intelligence rather than the ability to memorize patterns from training data, is designed to be easy for a human but devilishly difficult for current AI. Each puzzle is unique, requiring visual abstraction, causal reasoning, and generalization to situations never seen before. On ARC-AGI-1, TRM achieves 44.6% accuracy, surpassing HRM's 40.3% but also the 37% of Gemini 2.5 Pro with massive test-time compute, the 34.5% of o3-mini-high, and the 28.6% of Claude 3.7 Sonnet with a 16K token context.

On ARC-AGI-2, the even more difficult version of the benchmark released this year, TRM scores 7.8% against HRM's 5%, Gemini 2.5 Pro's 4.9%, and o3-mini-high's 3%. These numbers may seem low in absolute terms, but they represent huge performance leaps on a test where even the most advanced models struggle to break single-digit percentages.

To be fair and complete, we must mention that truly cutting-edge models like Grok-4-thinking achieve 66.7% on ARC-AGI-1 and 16% on ARC-AGI-2, while the Bespoke version based on Grok-4 reaches an astonishing 79.6% and 29.4%. But we are talking about a model with 1.7 trillion parameters, over two hundred and forty thousand times larger than TRM. It's like comparing a Smart Fortwo to a semi-trailer truck and finding that the Smart still manages to arrive first on certain particularly winding roads.

The real masterstroke, however, concerns training efficiency. Where large LLMs require massive datasets scraped from the entire internet and months of processing on clusters of thousands of GPUs, TRM is trained with just a thousand examples per problem. On Sudoku-Extreme, the full training takes less than 36 hours on a single 40GB L40S GPU. For ARC-AGI, it takes about three days on four H100s. We are talking about resources accessible to a university lab or a well-funded startup, not infrastructure costing tens of millions of dollars.

Distributed Intelligence: An Underground Movement

TRM is not an isolated case but part of a broader movement emerging at the fringes of the AI industry. As we have documented in recent months, there is a growing trend among startups with limited budgets and independent researchers to seek solutions that prioritize architectural cleverness over sheer computational power.

Take the case of DeepConf, a technique discovered by Jiawei Zhao during his internship at Meta in 2024. Zhao showed that if instead of asking an LLM for a single answer, you have it generate multiple alternative answers, then have them discuss among themselves in a structured way, and finally aggregate the conclusions, you get huge performance improvements on complex reasoning tasks. The underlying principle is similar to TRM's: iterate, reflect, refine. It's not just about how big your model is, but how you use it.

Even more fascinating is the case of MemVid, an experimental project that addresses a completely different problem but with the same underlying philosophy. Instead of building increasingly massive and expensive vector databases to manage the long-term memory of AIs, MemVid encodes information into QR codes and compresses them into MP4 video files. It sounds crazy, but it works extraordinarily well, leveraging thirty years of video codec optimizations to achieve compression ratios 50-100 times better than traditional databases, while maintaining sub-second semantic searches. Again, it's not a matter of throwing more computational power at the problem, but of finding a more elegant and intelligent solution.

What all these approaches have in common is a fundamentally different vision of what it means to build artificial intelligence. The mainstream industry, dominated by giants like OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic, has for years followed the "scaling" paradigm: more parameters, more data, more compute. The famous "scaling law" suggested that performance would improve predictably simply by increasing the scale. And it worked, for a while. But now we are seeing increasingly evident diminishing returns, along with environmental and economic costs that are becoming unsustainable.

The movement towards efficiency, on the other hand, starts from a different premise: intelligence is not just a matter of the quantity of information processed, but of the quality of the processing. It's the difference between reading a thousand books hastily and reading ten with deep attention, critically reflecting on each passage, making connections, and revising one's conclusions. TRM, DeepConf, MemVid, and dozens of other emerging projects are all exploring variations on this theme: iteration, reflection, architectural optimization.

The Architecture of Miniaturized Thought

To truly understand why TRM works so well despite being so small, we need to delve into the technical details of its architecture. As the original paper explains in detail, TRM consists of four essential elements: an embedding module that transforms the input into vector representations, a single recursive network of just two transformer layers, a latent "scratchpad" where internal reasoning occurs, and an output module that transforms the refined representations into the final answer.

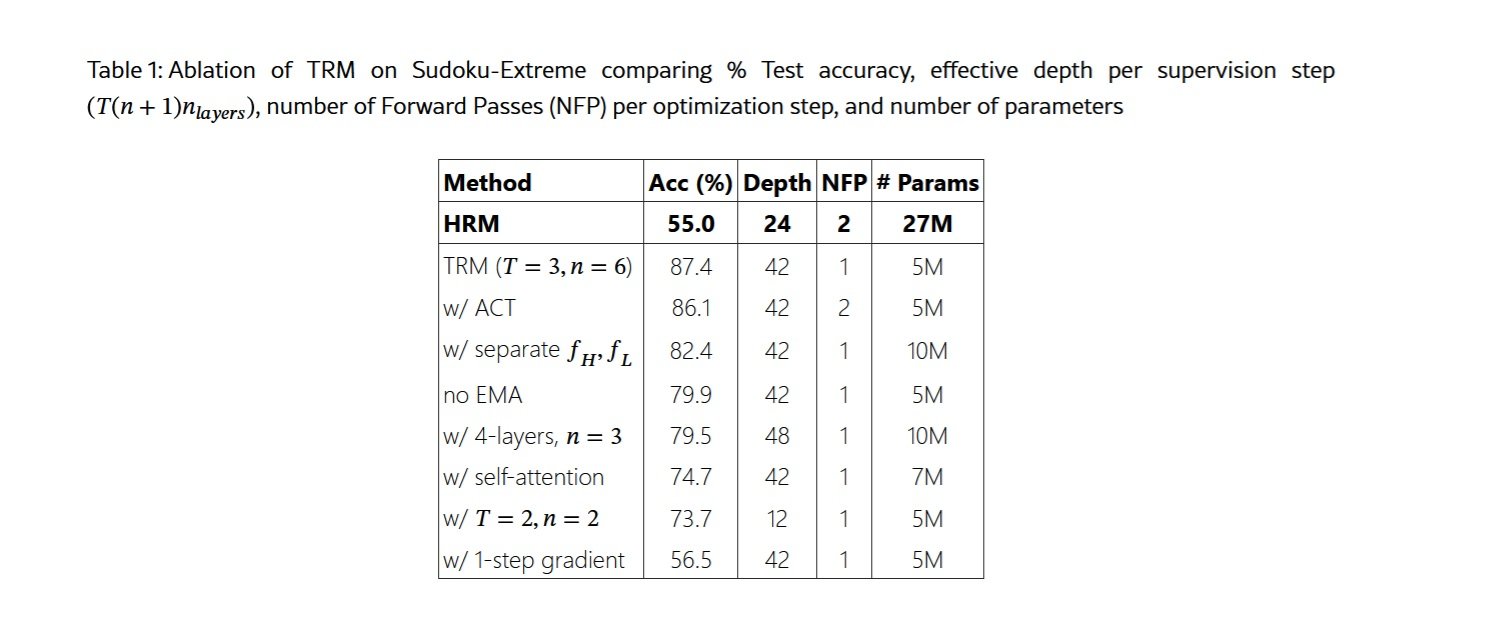

The keystone is the full recursive process. Unlike HRM, which relied on the implicit function theorem with a one-step approximation to justify backpropagating only through the last two steps, TRM backpropagates through the entire recursive process. This eliminates the problematic theoretical assumptions of HRM, which could not guarantee that it had actually reached a fixed point, and provides more accurate gradients for learning.

The process works like this: starting with the embedded question and an initial answer, TRM performs n iterations on its latent variable z, which represents its "internal reasoning." In each iteration, the network takes the input question x, the current answer y, and the current reasoning z, and produces an updated reasoning. This is done n times in a row, say 6 times, allowing the model to build an increasingly refined understanding. Then, using this refined reasoning z and the current answer y, the network produces a new, improved answer y. This constitutes one "full recursive process."

But it doesn't end there. Through "deep supervision," TRM can perform up to 16 of these full recursive processes in sequence, each time starting from the improved answer of the previous step and continuing to refine. It's as if a student solves a problem, re-checks their work, makes corrections, re-checks again, makes further corrections, and so on until they are completely sure of the solution. With n=6 latent reasoning iterations and 16 supervision steps, TRM effectively performs about 42 recursions of emulated depth, achieving a reasoning capability that would normally require a much deeper and more complex network.

One of the most counterintuitive insights reported in the paper concerns the size of the network. The researchers found that increasing the number of layers worsens performance due to overfitting on the small datasets typical of reasoning tasks. By reducing from four to two layers and compensating with more recursions, they achieved an improvement from 79.5% to 87.4% on Sudoku-Extreme, while simultaneously halving the number of parameters. Less is truly more when you have very little data and are seeking true generalization rather than memorization.

Equally interesting is the choice to eliminate the attention mechanism for tasks with small and fixed context lengths. Taking inspiration from the MLP-Mixer, TRM replaces self-attention with simple multilayer perceptrons applied to the sequence dimension. For 9x9 grids like in Sudoku, this leads to an improvement from 74.7% to 87.4%. However, for tasks with larger contexts like 30x30 mazes or ARC-AGI, self-attention remains superior, demonstrating that there is no universal solution, but the architecture must be adapted to the specific problem.

The Achilles' Heel and the Real Challenges

It would be dishonest to present TRM as a universal panacea without discussing its significant limitations. The first and most obvious one concerns its domain of application: TRM is specifically designed for structured reasoning problems with fixed-form inputs and outputs. It cannot chat naturally, it cannot generate creative text, it cannot answer open-ended questions like ChatGPT does. It is a surgical specialist, not an all-purpose generalist.

The second limitation concerns computational scalability during training. Backpropagating through 42 recursions requires a lot of memory, and the paper honestly documents how increasing the number of recursions too much quickly leads to "Out Of Memory" errors even on 80GB GPUs. This places a practical limit on the depth of reasoning that TRM can achieve, at least with current training techniques.

A third concern is generalization beyond the training domains. Yes, TRM generalizes beautifully within its domain, solving never-before-seen Sudoku or mazes with great accuracy. But what happens if you present it with a completely different type of puzzle, or if you try to apply it to a task that doesn't fall into the "structured reasoning" category? The paper does not provide definitive answers to these questions, and it is plausible to think that significant retraining would likely be needed.

Furthermore, TRM is inherently deterministic: given a question, it produces a single answer. In many real-world contexts, questions have multiple valid answers or require creative exploration of the solution space. As the authors themselves note in the paper's conclusion, extending TRM to generative tasks would require substantial architectural changes.

There is also a more subtle but important issue: TRM still requires supervised training with labeled examples for each new task. It cannot do "few-shot learning" in the way that large LLMs do, where you can describe a new problem with a few examples and the model immediately understands what to do. This means that for each new application domain, data must be collected, appropriate augmentations designed, and dedicated training conducted.

On a practical level, there is also the issue of infrastructure and ecosystem. Large LLMs benefit from years of development of tools, libraries, best practices, and a huge community of developers. TRM is a young open-source project, with all the challenges that this entails in terms of documentation, support, debugging, and integration with other systems.

The Economic Context: Why Now?

To understand why approaches like TRM are emerging right now, we need to look at the economic reality of AI in 2025. The costs of training and deploying large language models have become prohibitive for anyone who isn't a tech giant. As we discussed in the article on MemVid, building even a small AI data center costs between $10 and $50 million, not to mention recurring operational costs. The vector databases needed to manage the long-term memory of these systems have become multi-billion dollar industries, with the market reaching $2.2 billion in 2024.

This concentration of capital is effectively creating an AI oligarchy, where only five or six companies in the world can afford to compete at the highest level. OpenAI has raised billions, Anthropic likewise, and Google and Meta can draw on the profits of their core businesses. But for the thousands of startups, university labs, and independent researchers, the scaling race is simply out of reach.

TRM and similar approaches represent a democratization of advanced AI. With a few tens of thousands of dollars in cloud resources, a small team can now train models that beat the giants on specific tasks. This is drastically lowering the barriers to entry and allowing for the exploration of a much more diverse landscape of architectures and approaches.

There is also an environmental dimension that cannot be ignored. The data centers that train the largest models consume the electricity of small cities, with carbon footprints measurable in thousands of tons. A model like TRM, trainable on a single GPU in less than two days, has an environmental impact that is literally ten thousand times smaller. In an era of growing awareness of the climate crisis, this is not a marginal consideration.

The Applications That Change the Rules

Where might it make sense to deploy TRM in the real world? The answer lies in domains where deep structured reasoning is critical, data is scarce, and computational resources are limited.

The first field that comes to mind is robotics, especially for edge devices that need to make complex decisions in real time without being able to rely on constant cloud connections. An industrial robot that needs to plan optimal movement sequences, or an autonomous drone that must navigate through complex environments, could benefit enormously from a model like TRM that can "think deeply" using minimal computational resources.

In the medical field, tasks such as diagnosing rare diseases or planning complex therapeutic strategies require exactly the kind of abstract reasoning and generalization at which TRM excels. As we mentioned in the article on HRM, similar models have already demonstrated 97% accuracy in seasonal climate predictions, suggesting that the same approach could work for medical predictions based on complex patterns.

Education could see fascinating applications. Imagine personalized tutoring systems that can truly "understand" where a student gets stuck in math or physics, not just by providing the right answer but by guiding their reasoning through logical steps. TRM, with its ability to iterate on complex problems and its relative transparency compared to the black boxes of giant LLMs, could be ideal for this type of application.

In the field of cybersecurity, tasks like analyzing malicious code, detecting sophisticated attack patterns, or formally verifying cryptographic protocols require deep reasoning about complex structures. These are exactly the contexts where a small but intelligent model beats a giant that has seen the entire internet but doesn't really know how to reason.

Finally, there is the whole world of embedded AI: IoT devices, industrial sensors, autonomous vehicles, where the idea of constantly sending data to the cloud for processing is impractical due to latency, cost, or privacy constraints. As we have seen with MemVid and now with TRM, efficient AI opens up completely new scenarios for distributed intelligence at the edge of the network.

The Debate: Specialists vs. Generalists

The emergence of approaches like TRM is reigniting a fundamental debate in AI: is it better to have gigantic, generalist models that do everything decently, or an ecosystem of specialized models that excel in their specific domains?

The current paradigm favors generalists. OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google are all aiming for increasingly large and capable models that can do "everything": write code, analyze images, conduct natural conversations, solve math problems, and so on. The idea is that with enough parameters and enough data, a kind of general intelligence will emerge that can adapt to any task.

But this strategy has enormous costs. Every time GPT-5 or Claude 4.5 is released, it requires orders of magnitude more resources for training. The vast majority of these resources go to marginally improving performance on tasks that we may not even care about. If you use GPT-4 primarily for analyzing scientific data, you are still paying for all the training that went into teaching it to write poetry, play text-based role-playing games, and a thousand other things.

The specialist approach, which TRM represents, proposes a modular architecture instead: small, optimized models for specific tasks, which can be combined into more complex systems when needed. Do you want a complete AI assistant? Use a small LLM for language understanding and conversation, a TRM for complex reasoning, a specialized model for vision, another for code generation. Each component does its part exceptionally well, and together they cover a broad spectrum of capabilities.

This modular approach has significant advantages beyond pure efficiency. It allows for independent component updates, easier debugging because you know exactly which module is failing, and superior transparency because the flow of information between specialized modules is more traceable than the inscrutable thinking of a monolithic giant.

However, there is also a disadvantage: generalist models show emergent capabilities that arise from the interaction of all their parts. Phenomena like "transfer learning," where knowledge acquired in one domain helps in completely different domains, or the ability for "chain-of-thought," where the model spontaneously learns to reason step-by-step, seem to require a certain scale. If you fragment too much, you might lose this emergent magic.

My feeling is that we will see a convergence between the two approaches. Large generalists will continue to exist for applications where they are truly needed, but most real-world deployments will likely use hybrid systems: small specialized models for critical tasks where efficiency matters, coordinated by larger models when needed for tasks requiring extreme flexibility.

Beyond Benchmarks: What's Still Missing

As impressive as TRM's results on benchmarks are, it's important to maintain a critical perspective on what these numbers really tell us and what they leave out. Benchmarks like ARC-AGI, however well-designed, remain controlled and artificial environments. Real-world reasoning is often much more complex, ambiguous, and context-dependent.

A fundamental limitation is the lack of robustness to adversarial inputs. Published benchmarks have well-defined formats, but in the real world, inputs are often noisy, incomplete, or deliberately misleading. An AI system deployed in production must handle users asking poorly formulated questions, data with errors, and edge cases that no one had anticipated. We do not yet have data on how TRM performs in these scenarios.

Then there is the issue of continuous learning. TRM is trained on a static dataset and then frozen. But the real world is constantly changing: new types of problems emerge, domain rules evolve, standards change. Large LLMs can be fine-tuned or updated through techniques like RLHF, but it is unclear how easily TRM can adapt without complete retraining.

Explainability is another gray area. Yes, TRM is more transparent than the giants in that we can observe how its latent state evolves through recursions. But that latent state still remains a multi-dimensional vector in a space that does not directly correspond to interpretable human concepts. When TRM makes a mistake, how easily can we understand why and correct the problem?

On the security front, small and efficient models like TRM raise new questions. If it becomes possible to train highly capable models with modest resources, this also drastically lowers the barriers for malicious actors. A group with malicious intent could train a TRM specialized in tasks like finding software vulnerabilities, generating exploits, or optimizing attack strategies. The democratization of AI is desirable, but it brings with it responsibilities that the community has yet to fully address.

Finally, there is the question of evaluation itself. Current benchmarks, however difficult, primarily measure abstract reasoning abilities on well-defined problems. But much of human intelligence is about navigating ambiguity, managing uncertainty, integrating knowledge from different domains, and reasoning about open systems without clear boundaries. How much of this more nuanced intelligence can TRM capture? The paper does not provide answers, and it will likely take years of research to find out.

The Research Frontier: What Comes Next

Looking at the immediate future, there are several promising directions that research on recursive architectures like TRM could explore. The first and most obvious is the extension to generative tasks. As mentioned in the Samsung paper, TRM currently produces deterministic outputs, but many real-world problems require exploration of the solution space, generation of multiple alternatives, and probabilistic evaluation of options. Integrating sampling mechanisms and uncertainty evaluation into TRM could open up completely new applications.

A second frontier concerns transfer learning between domains. Currently, TRM is trained separately for each task, but there are hints in the paper that suggest interesting possibilities. The fact that the same architecture works exceptionally well on Sudoku, mazes, and ARC-AGI puzzles, which are superficially very different, suggests that TRM is learning something more fundamental about abstract reasoning. We could imagine pre-training on a broad spectrum of reasoning tasks, followed by rapid fine-tuning on specific domains.

The third direction involves integration with symbolic systems. TRM operates entirely in the sub-symbolic domain of neural networks, but many complex reasoning problems in the real world would benefit from integration with logical inference engines, constraint solvers, or symbolic planners. Hybrid systems that combine TRM's ability to learn patterns from data with the precision and verifiability of symbolic reasoning could be extremely powerful.

On the efficiency front, there is still room for improvement. The paper mentions that increasing the number of recursions quickly leads to memory problems, but techniques like gradient checkpointing, quantization, or more memory-efficient architectures could allow for even deeper recursions on the same hardware. Similarly, optimizations at the compilation level and specialized hardware for recursive operations could further accelerate training and inference.

A particularly fascinating direction concerns meta-learning: training TRM to learn how to learn. Instead of manually training for each new task, we could imagine a system that, given a few hundred examples of a completely new problem, automatically determines the optimal architecture, the necessary number of recursions, and the appropriate augmentation strategies. This would likely require a higher level of abstraction, perhaps a "meta-TRM" that reasons about how to configure TRM for specific tasks.

The Lesson from One Punch Man: When Basic Training Beats Raw Talent

There's a metaphor from pop culture that comes to mind when thinking about TRM. In One Punch Man, the protagonist Saitama gains literally invincible strength not through special powers or advanced technology, but through an absurdly simple and repetitive training regimen: one hundred push-ups, one hundred sit-ups, one hundred squats, and a ten-kilometer run, every single day. The other heroes with their exotic and complex powers look at him perplexed, but Saitama surpasses them all precisely through that methodical and obsessive repetition.

TRM is a bit like that. Where the AI giants accumulate billions of parameters and increasingly elaborate architectures, TRM takes a tiny two-layer network and has it recurse on itself again and again and again, with almost Zen-like patience. No complicated theorems, no elaborate biological justifications, just disciplined recursion and deep supervision. And it works better.

This lesson has implications that go beyond TRM's specific architecture. It suggests that in the field of AI, as in many others, we may have reached a point of diminishing returns from the mere accumulation of complexity. Architectural elegance, a deep understanding of learning mechanisms, and intelligent optimization could bring further gains than simply "making everything bigger."

Towards an Ecology of Artificial Intelligence

One of the most interesting prospects opened up by TRM and similar approaches is the idea of an ecology of artificial intelligence, rather than a monoculture dominated by a few giants. In nature, the most robust and adaptive ecosystems are not those dominated by a single super-predator, but those characterized by diversity: countless species, each optimized for its own niche, interacting in complex networks of symbiosis and competition.

We could imagine a similar future for AI. Instead of an industry where five companies control five giant models that try to do everything, we could have thousands of specialized models, each excellent in its own domain. TRM for abstract reasoning, MemVid for efficient memory management, specialized models for vision, for natural language, for planning, for continuous learning. These models could be developed by a global community of researchers, open, verifiable, and composable.

This paradigm would have enormous advantages. First, it would reduce the concentration of power we are seeing in AI, where a few corporations de facto control access to advanced artificial intelligence. Second, it would allow for much faster innovation, because small teams could contribute improvements to specific components without having to compete in training gigantic models. Third, it would improve the overall robustness of the system, because the failure of one component would not compromise the entire stack.

Of course, this would require coordination infrastructures, interoperability standards, and governance mechanisms that do not currently exist. But open-source projects like TRM on GitHub are laying the groundwork for this vision, demonstrating that it is possible to develop and share advanced AI openly.

The Road Ahead: Predictions and Hopes

Looking at the next few years, it is reasonable to expect that we will see an explosion of variations and improvements on the theme of recursive reasoning. TRM has shown that the approach is viable and powerful, but like any significant innovation, it opens up more questions than it answers. Other labs are already exploring variations: recursive models with different attention mechanisms, architectures that dynamically learn how many recursions to use for each problem, systems that combine recursion with retrieval of external information.

On the industrial front, I expect to see relatively rapid adoption in specific domains where TRM's advantages are overwhelming. Robotics, autonomous vehicles, embedded systems, and edge applications where efficiency is critical are obvious candidates. We might also see startups offering "TRM-as-a-Service" for specific reasoning tasks, competing with the giants precisely on the ability to do more with less.

In the academic world, TRM provides a new framework for exploring fundamental questions about learning and generalization. Why does recursion work so well? What is TRM actually learning in the latent space during its iterations? How can we formally characterize the class of problems for which this approach is optimal? These are research topics that will keep PhDs and post-docs busy for years.

There is also a geopolitical dimension to consider. The concentration of advanced AI in a few American and Chinese companies has created concerns in Europe and other regions. Approaches like TRM, which drastically lower the barriers to entry, could allow countries with fewer computational resources to still develop advanced AI capabilities. This could partially rebalance the global AI landscape, with implications for economic competition, national security, and international governance of the technology.

Final Thoughts: Intelligence as a Process, Not a Product

TRM reminds us of a fundamental truth that the AI industry had perhaps forgotten in its race to scale: intelligence is not a matter of size, but of process. It doesn't matter how big your model is or how many parameters it contains. What matters is how it processes information, how it iterates on its reasoning, how it progressively refines its conclusions.

This insight resonates with our human experience. The most intelligent people we know are not necessarily those with the biggest brains or the most neurons. They are the ones who think methodically, who consider problems from multiple angles, who review their own conclusions, who learn from their mistakes. In other words, they are the ones who effectively iterate on their own reasoning process.

If there is one lesson we can draw from the emergence of TRM, DeepConf, MemVid, and the broader trend towards efficiency in AI, it is that the future will not necessarily belong to the biggest, but to the smartest. The industry is slowly waking up to the realization that throwing more resources at problems has diminishing returns, and that intelligent architectural innovation can produce qualitative leaps that mere scaling will never achieve.

Like the small Saitama from One Punch Man who defeats cosmic monsters with his basic training, or like the tiny Luke Skywalker who learns that the Force is not about size, TRM shows us that in AI, the old adage still holds true: it's not how big you are, it's how you use what you have.

And in a world where computational and environmental resources are increasingly under pressure, where the concentration of technological power raises legitimate democratic concerns, and where access to advanced artificial intelligence could determine the success or failure of entire economies, this lesson could not come at a more opportune time.

The Samsung SAIL Montreal paper is not just a technical innovation. It is a manifesto for a different way of thinking about artificial intelligence, one that prioritizes elegance over brute force, accessibility over concentration, sustainability over indiscriminate growth. If this approach catches on, and all signs suggest it will, we may look back at TRM as the turning point where the AI industry finally learned that smaller can indeed be smarter.